After the Levellers: On the Non-Mysterious Disappearance of Parliamentary Reform in England

The dog that did not bark. It is one of the mysteries of the history of English thought on parliaments and representation that between the era of the Levellers in the 1640s and the Wilkesite movement in the 1760s the question of the franchise disappeared almost entirely. The franchise remained narrow and was not overhauled until the Reform Act of 1832. The Levellers have often been called ‘the first English democrats’, and, while there remains room for dispute about the extent of their commitment to adult male suffrage, it was surely an epochal moment when rank-and-file soldiers sat down in Putney Church, after the defeat of the king in the Civil War, to debate a new constitution. But, after the Levellers, silence. Neither the radical Whigs nor the neo-republicans of the late seventeenth century showed much interest in the franchise. And, when fleetingly the Whigs did do so, it was to propose reducing it, on the grounds that only a substantial income gave a man enough sturdy independence to resist the bribery of courtiers and the bullying of caucuses.

The Putney Debates (1647). Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo.

The silence is the more strange when we remind ourselves that in this same period the idealisation of parliament as the embodiment of the nation reached its apogee. Unquestionably central to the Revolution of 1688 was the claim that Stuart monarchs posed a mortal threat to parliaments. The idea that legislative sovereignty lay with parliament and that parliament was the nation became dogma.

And yet we surely wish to avoid the condescending anachronism, which filled twentieth-century democratic textbooks, that dismisses pre-1832 Britain as the era of the ‘Unreformed’ House of Commons. Finding the post-Leveller period wanting by the standards of the modern mass franchise won’t do as intellectual history. So, rather than dwell on the silent franchise question, I’d like to highlight four themes that ran through Anglophone debate and practice after the Levellers.

The first is the weight given to the doctrine of virtual representation. The few were taken to stand for the whole. (Before the Civil War, sometimes a person was made MP by public acclamation, without a poll and without ascertaining the voting rights of those who gathered to ‘huzza’.) We are apt to boggle at the elasticity of the doctrine of virtual representation in the eighteenth century. But all electoral systems in modern democracies still rely unavoidably on the notion. Everybody is deemed represented even when the turnout is tiny (one ward in Hull had a turnout of 12.7% in the 2019 general election). And everybody is deemed represented even when most people voted for different candidates.

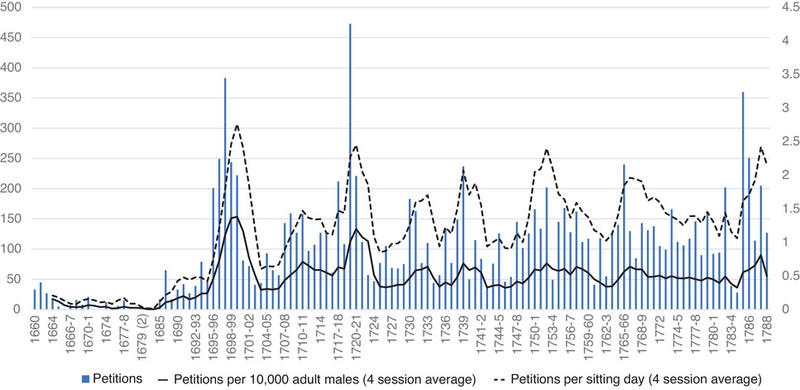

Petitioning parliament, from: Philip Loft, 'Petitioning and Petitioners to the Westminster Parliaemnt, 1660-1788', Parliamentary History, 2019.

This first doctrine, virtual representation, entrenched and underwrote the alchemy by which parliament represented even though the franchise was small. The second theme pushed in the opposite direction. It is the doctrine that MPs were accountable to the whole community. Where Edmund Burke insisted that an MP should act upon his own wisdom, and was not a mere delegate or mouthpiece of constituents, there was a vibrant tradition that implied a doctrine of delegacy. This was a modernised version of the ‘direct’ democracy of ancient Athens. If, in modern states, representation was necessary, it could be asserted that MPs must follow electors’ instructions and petitions. The early Whig movement around 1680 saw the development of instructions by constituents. Of great importance was the Kentish Petition of 1701, when it was held that MPs were bound by the demands of petitioners, and ought ‘to have regard to the voice of the people’. Today, there are parallels in the practices of the Left: the ‘mandating’ of delegates, and demands for a right of recall. A modest version of ‘recall’ has recently entered the formal constitution, under the Recall of MPs Act (2015), which specifies circumstances, involving a petition, that automatically require an MP to vacate their seat and face a by-election.

The Recall of MPs Act (2015).

The third theme by-passes the preoccupation with parliament and voting altogether, indeed suggests that it is anachronistic to suppose that early modern people thought of citizenship in terms of polling. Rather, they thought in terms of holding office. If they were learned, they read Cicero’s De Officiis (On Offices - or Duties). Thousands of early modern people held office but did not have the parliamentary franchise. Every parish had a constable, churchwardens, overseers of the poor, chosen by vote, or rotation, or ‘houserow’. People served in militias, were watchmen of the ward, governed charitable orphanages and almshouses. To talk of the ‘restricted’ parliamentary franchise disguises the vibrant civic life of England’s myriad miniature parish and borough republics. Arguably, that quasi-republican tradition offered a far richer idea of citizenship than our own etiolated reduction of citizenship to a quinquennial scratching of an ‘X’ on a ballot paper.

Fourth, there was what might, perhaps unsatisfactorily, be called ‘corporatism’. One impediment to universal franchise thinking was the absence of the individualism implied by it. What parliament represented was not individuals but corporate bodies: counties and boroughs. That some were large and some were small, some ‘open’ and some ‘closed’, did not matter. The great commonwealth embodied the little commonwealths of shires and chartered boroughs. The violation and manipulation of chartered corporations by Charles II and James II was high on the charge sheet in the Revolution of 1688.

The corporatist model of representation is scarcely absent today. In the US Senate, Rhode Island has the same representation as California, and in the United Nations General Assembly, Vanuatu as India. Arguably Britain’s use of the House of Lords is quasi-corporatist, filled as it is with ‘representatives’ of faith groups, people of colour, professions, trade unions, universities, and variegated strands of civil society. Much contemporary identitarian politics is corporatist in implication: it is collectivities that demand representation. Contemporary political discourse modernises the ancient notion of representing ‘estates’, now through the language of ‘stakeholders’.

There is a little-known ‘corporatist’ moment in English thought, dating from 1695. Demands became loud for the creation of a Council of Trade. What emerged was the Board of Trade and Plantations, a small body, comprising politicians and a working team of ‘civic virtuosi’ appointed by the crown. What pamphleteers had demanded was a grand national, indeed transnational, council. Their schemes reveal expansive and radical thinking, albeit directed not to parliament but to a new body. One of them proposed an imperial-cum-commercial body, with representatives of the principal trading companies, the chief manufacturing towns, and the American and West Indian colonies. (It anticipated early twentieth-century proposals for an imperial parliament representing all of Britain’s global empire.) The core assumption in these projects was corporatist.

John Locke. Illustration by Jim Godfrey, Cathedral Verger at Christ Church, Oxford.

John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1689) captures our paradoxes. Here is a theorist of revolution and popular sovereignty who showed scant interest in the franchise. He himself probably never voted in a parliamentary election; and never complained about this. In paragraph 213 of the Second Treatise, he blithely invites the reader to assume a parliament comprising a ‘single hereditary person’, ‘an assembly of hereditary nobility’, and ‘an assembly of representatives chosen by the people’ – very English, and undemocratic. A number of political scientists still piously insist that Locke was implicitly a democrat. Yet he was certainly not a franchise democrat. True, he did think that you were not a citizen of a polity unless you personally consented to be so – though it remains unclear who counts as ‘citizen’ and what counts as ‘consent’. But even if he were universalist about membership of the polity, he drew a sharp distinction between that, and voting for its parliament. He and the Whigs cared passionately about oaths of allegiance; they wanted to use Revolution oaths to purge backsliders: Jacobites and Tories. In 1696 a remarkable exercise in (male) democracy occurred. After an assassination attempt upon William III, the Oath of Association was sworn, in many communities by the entire adult male population. In the tiny hamlet of High Laver in Essex, where Locke lived, every adult male took the Oath: you will find Locke’s signature alongside many who scratched their marks because they were illiterate. Over forty villagers swore the Oath; only three had parliamentary votes. For Locke, allegiance – consenting to the commonwealth – was democratic; but the franchise was not.

John Locke. Illustration by Jim Godfrey, Cathedral Verger at Christ Church, Oxford.

Let us look finally at Locke’s brief remarks on franchise reform. Their tone is corporatist. He notes that in the (economic) ‘flux’ of the world, ‘people, riches, trade, power, change their stations’. That, by ancient custom, representation was still conferred on decayed and deserted boroughs was a form of ‘corruption’. He means that places, living communities having a distinct socio-economic character, should be represented, and that reform should look to enfranchising places newly thriving with mercantile wealth. He pointed to the constitutional importance of ‘the power of erecting new corporations, and therewith new representatives’. In his economic tracts we catch a glimpse of where he might be thinking of, for he mentions ‘places wherein thriving manufactures have erected themselves’, naming Taunton and Exeter, which did have MPs, and Halifax, which did not. To attribute modern individualism to Locke belongs to the fable of liberalism.

Mark Goldie, Professor Emeritus of intellectual History, University of Cambridge; Honorary Professor of History, University of Sussex.