An Aesthetic of Science in British Imperial Cartography of the Caribbean, c. 1700-1775

When Great Britain emerged victorious from the Seven Years’ War in 1763, the Board of Trade inaugurated a campaign to produce topographical maps of its new imperial possessions. Britain had become the dominant colonial power in the Atlantic and Caribbean world, and was keen on using its maritime authority to bring island territories into the fold of its imperial gaze. A prime example is This Map of the Island of Jamaica, completed in 1763 by engineers Thomas Craskell and James Simpson, which cast a scientific interpretation over the profitable lands and plantation economies Britain had fought so recently to defend.

This Map of the Island of Jamaica by Thomas Craskell and James Simpson (1763) © Library of Congress

The makers of these maps prioritized topographical accuracy above all else. However, the reality was far from this. Under the veneer of objectivity and empiricism, the very aesthetics of these maps embodied the political prejudices of 18th century British imperialism. Everyday realities of plantation society are reduced to a symbolic ledger. Bite-sized symbols of boat anchors, sugar plantations, and “Negro Towns” dissolve into the etchings of Jamaica’s mountain ranges and depressions. Science sterilized the depiction of prosaic experience.

When writing recently about imperial mapmaking, I sought to reconcile imperial cartography’s hyper-scientific tendencies with its simultaneous reality of political violence. A scientific aesthetic was born from these cartographic projections, one that masked a paradox between enlightened civility and violent expansion. Linking this paradox was an interpretation of science and the arts that constructed an image of Enlightenment and empire.

A closer look at Craskell and Simpson’s map reveals the philosophic underpinnings of their cartographic practice. On the map’s dedicatory frontispiece is an obelisk flanked by two classical figures who crown an effigy of King George III. They are surrounded by symbols of what an eighteenth-century viewer would have interpreted as tools of learned refinement. A circumferentor, a telescope, and a terrestrial globe frame the frontispiece’s right edge. Above them are an artist’s palate and a spring compass. Instruments of the arts and sciences unite into a conceptual framework by which colonies might be studied, forming a universal system of knowledge that could comprehend the entirety of the physical world.

Enlightenment science sought to uncover what it perceived to be orderly and harmonious patterns of the natural world, as did the Enlightenment’s philosophy of aesthetics. Lord Kames, for example, argued in his Elements of Criticism (1762) that any fit aesthetic theory must support a system of visual representation aligned with social order. Kames dedicated Elements to George III, then a principal collector of maps of his new overseas possessions, and for whom the cartographic collection is named at the British Library today.

Empire’s simultaneous ability to produce intellectual refinement and violent displacement required representational practices that reconciled seemingly irreconcilable practices. Cartography was the answer to this. More specifically, it was imperial cartography’s scientific aesthetic – an approach to representation informed by late eighteenth-century imperial Britain’s captivation with science as a standard of intellectual and political order – that made possible an image of Enlightened civility within the arena of empire building.

In the later decades of the eighteenth century, topography became the preeminent method of representing cartographic knowledge. Its increase was largely fueled by the continental politics of the Seven Years’ War. The resulting reshuffle of colonial possessions led many European governments to organize topographical surveys of their new territories, creating exhaustive and standardized observations of entire regions. These maps became an apparatus of the state.

Take, for example, the surveys contained in one of the most popular atlases of late eighteenth-century Britain, the West India Atlas (1775) surveyed and engraved by George III’s official cartographer, Thomas Jeffreys. The depiction of Caribbean islands in Jeffreys’ Atlas highlights a broader trend towards an aesthetic of topographic science. The island is divided into its principal administrative divisions with toponyms of key bays and shoals outlining the coastline. The island’s interior is laden with phrases that indicate the number of plantation estates in each division, but it does not reference the surnames of their owners.

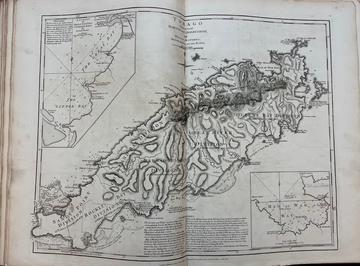

TOBAGO from Actual SURVEYS and OBSERVATIONS in The West India Atlas (1775), Weston Library

A discord of hatched, parallel black lines in the North East Division creates tone and shading. Gradual increases in the thickness and closeness of lines give the illusion of elevation, particularly along the Main Ridge of the Island. Oval-shaped hatching outlines throughout the map indicate mountainous plateaus. Dotting is used to portray water depth of the Great River Shoal. To the Shoal’s left are two, three-dot groupings that denote “Indians” grounds. Rather than including figural representation, the presence of non-European peoples had been flattened to dots and a single word. Unlike Caribbean maps from the earlier Enlightenment, symbols and caricatures of crops, people, and estates have been subsumed by a rationalized and scientist portrayal.

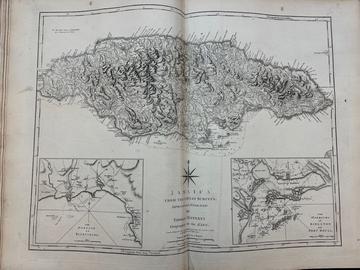

Jeffreys’ depiction of Jamaica is no different. In the second half of the eighteenth century, Jamaica surpassed Barbados as Britain’s most profitable sugar colony, a reality reflected in this map’s topographical yet highly political mapping practice. Shading gives the illusion of a jagged mountain range; rives of similar gradation run throughout the island. In addition to the toponyms of bays and parishes, there are named descriptions of natural land masses like The Blue Mountains and the Savana Mountains. Small dots abound the interior, likely in reference to plantations given their repeated use to represent plantations across most of Jeffreys’ maps. “Negro Towns” are indicated by an underline of the town’s name. All underlines are all concentrated within the inland mountainous region, suggesting local topography and climate made these areas a banishing point for enslaved communities.

JAMAICA FROM THE LATEST SURVEYS in The West India Atlas (1775), Weston Library

Plantation society’s labor force was reduced to symbolic allusion. This is critical for two reasons. First, the map’s emphasis on topographical inscription reflects a heightened cultural sensibility to consume scientific knowledge perceived as empiric and faithful to real land. Second, the creation of this map mitigates the economic driving force of empire: enslaved labor. Geographic data was systematically collected and reproduced into a sanitized image of imperial order. The violence of mapmaking’s archive-like data collection and representation lays in its obfuscation of imperial reality via the anesthetization of scientific knowledge. This image of empire’s interiority was legible to the metropolitan eye. It would have augmented their understanding of empire according to the “benevolent” advancement of science, and with little conception of its grotesque realities.

Jeffreys himself described his Atlas as an improvement upon earlier English atlases that prior had been “unconnected, without order or method... prior to the nautical or topographical surveys which have been accurately taken, and which totally changed the Geography of this part of the World.” He builds upon a tradition in which geographers understood their work as an ever progressive distillation of sciences, the arts, and natural philosophy into a visible representation of inescapable political modernity. Emanuel Bowen, geographer to King George II, had even described his 1750s An accurate map of the West Indies as a prototype of “Geography Reformed,” or “A New System of General Geography. According to an accurate analysis of ye science; Augmented with Several Necessary Branches Omitted by former Authors.” The universal philosophy by which colonies could be studied and represented was bound by eighteenth-century British cartography’s fusion of the arts and sciences. A scientific aesthetic was born from these cartographic projections, one that masked a paradox between enlightened civility and violent expansion. Science and the arts converged to fashion the idea of an Enlightened empire.

Lauren Anderson is a 2023 graduate of the Master of Studies in Intellectual History at the University of Oxford. She previously obtained her Bachelor of Arts in Social Studies from Harvard University. This article is based on original research conducted for her master’s dissertation.