Journeys to the Moon in Ancient Greece

William Shatner has recently attracted widespread criticism for undertaking a 10-minute space flight with Jeff Bezos’ space travel company, Blue Origin. Two themes emerge clearly from interviews with Shatner about the experience: first, that travel away from the earth provides a new perspective on it; second, more subtly, that space is no longer a rarely-crossed frontier for scientific investigation, but a place, to which leisure travel is not only possible but becoming commercially realistic (if only for the super-rich).

It is not intuitive, in a world before space travel, that we would think of space, or even of the planets, as places in their own right. Two of the best-known early works which involve space travel are Athanasius Kircher’s Itinerarium Exstaticum (1656) and Emmanuel Swedenborg’s The Earths in Our Solar System (1758). Although these works involve all the planets, by the late nineteenth century, Mars and Martians had begun to occupy a disproportionately prominent place in fiction; the huge popularity of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898) has ensured that Mars has remained the primary focus of pop-cultural imagination about space travel.

Why did Mars become the most interesting planet to travel to? One possible reason is that with a good telescope, Mars can be seen quite clearly. In contrast, Venus is covered in clouds. Such observations became possible in the late nineteenth century. Asaph Hall’s observation of the Martian moons and Giovanni Schiaparelli’s observations of Mars’ canals sparked a great interest in Mars not just as an object, but as a place.

It is perhaps for this reason—its plausible placeness—that the moon has been the subject of stories about space travel for much longer. The earliest surviving Greco-Roman text about travel to the moon was written in the second century BC. It is Antonius Diogenes’ The Incredible Things Beyond Thule, a complex faux-memoir by an unnamed narrator. It describes the narrator’s journey to the ultimate northern reaches of the earth, and then, beyond, briefly, to the moon. Diogenes describes the moon as a ‘pure world’ (γῆν καθαρωτάτην). As Karen ní Mheallaigh points out in her recent book about the moon in Greek thought, the word for ‘pure’, καθαρός, is double-edged. Alongside its connotations of untouched beauty, it can also mean ‘sterile’.

In the early second century AD the satirist Lucian expanded on the theme of lunar travel in two of his works, Icaromenippus and True Stories. In Icaromenippus, the protagonist Menippus flies to the moon and looks down on the earth, contemplating his previous life from a distance. In True Stories, Lucian and his shipmates are recruited into a war between the inhabitants of the moon and the inhabitants of the sun. There are extensive descriptions of the moon people and their way of life: they are all male but reproduce through a hermaphroditic process, they have removable eyes, and they sweat milk. In their oddness, the moon people serve as a foil to think about the stranger features of human biology and culture.

A 1983 East German postcard that commemorates 25 years since the launch of Sputnik 1, and declares Lucian to be the father of space travel.

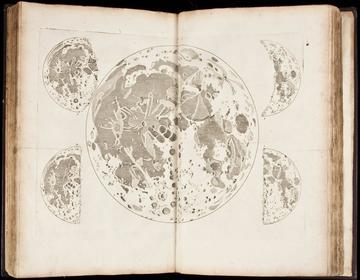

What are the conditions necessary to imagine the moon, other planets, or space itself as places one might visit? First, places have to be made of something. Many Bronze-Age cultures, including those in the Mediterranean, discussed the planets primarily as gods. By the Classical Greek period, some texts theorised about the physical make-up of the sun, moon, and stars. In most cases, the heavenly bodies were claimed to be made of fire, but Aristotle posited that they were made instead of a mysterious fifth element called aether. Plutarch’s On the Face in the Moon (late second century AD) is, by contrast, one of the first texts that suggests that the moon is physically like the earth, made of rock. The idea of placing one’s feet on the moon suddenly becomes possible with this insight.

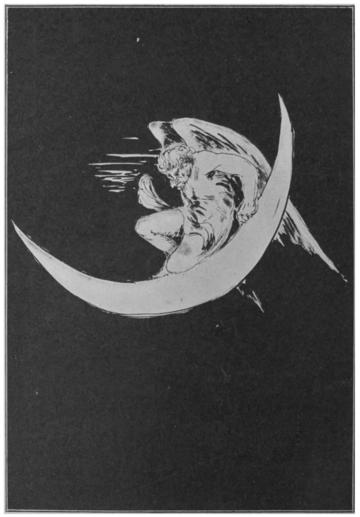

An illustration of Icaromenippus from the frontispiece of a book called A Voyage in Space by an astronomy professor called Herbert Hall Turner, who adapted it from some lectures he delivered at Christmas 1913.

Second, when we plan journeys, we want some idea of how far we will go. Greek mathematicians undertook speculative calculations about the size of heavenly bodies and their distance from the earth. In the third century BC, Aristarchus estimated the moon to be at a remove of 20 x the radius of the earth. Soon after, Eratosthenes estimated the circumference of the earth at around 252,000 stadia (c.29,000 miles, only 5,000 miles off the real value). Lucian’s Icaromenippus mocks mathematicians for their apparent certainty about the distance to the moon and claims instead that direct experience is the route to knowledge of the moon—but he is able to do so exactly because physical theories about the moon give him an acute sense of its physical reality.

Although modern science and pop culture are still fixated with Mars, the increasing possibility of commercial space travel returns us to the ancient question: what does it take for a part of the universe to become a place?

Claire Hall is an Examination Fellow at All Souls College, Oxford.