Christopher Hill: A Historian of Ideas?

The Centre for Intellectual History may mark a new departure for the University of Oxford, but the discipline has a long and vibrant past in this institution. The disaggregated and heterogeneous nature of this history—which may have forestalled any earlier attempts to carve out a formal place for intellectual history at Oxford—is marked by the same plurality of focus and method that the new Centre seeks to make a virtue.

One of the most peculiar intellectual historians in this tradition was Christopher Hill (1912–2003). Hill’s association with Oxford was intimate. Hill read for his undergraduate degree at Balliol, graduating in 1934, after which he migrated to All Souls. After a brief spell at Cardiff University, Hill returned to Balliol in 1938, where he served as a fellow either side of war work, until 1965, when he became Master.

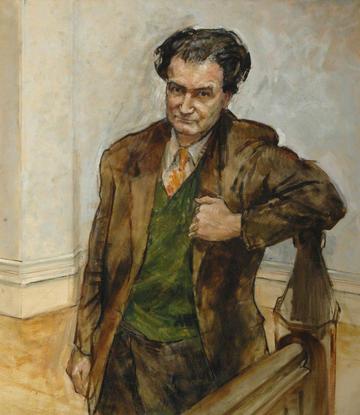

Portrait of Christopher Hill for Balliol College (1968) by Derek Hill

The association of Hill with intellectual history may, at first, appear less immediately convincing. The relationship between Anglophone Marxist history-writing and Anglophone intellectual history was, and remains, a vexed one. Superficially, they are often posed as opposites. Certainly, many practitioners of each have framed themselves explicitly against the perceived strictures and pitfalls of the other. Hill’s primary attempt at ‘high’ intellectual history—his Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution, developed from the 1962 Ford Lectures delivered at Oxford—was subject to much criticism by another idiosyncratic Oxford intellectual historian, Hugh Trevor-Roper.

Nonetheless, ideas were central to all of Hill’s work. By the end of his long career, Hill was glad that ‘in the course of the last two generations, the history of theology, law, philosophy, science, literature and art has ceased to be the exclusive preserve of theologians, lawyers, philosophers, scientists, literary and art critics… it has become the history of society.’ Hill’s most iconic work, The World Turned Upside Down (1972), was, after all, subtitled ‘Radical Ideas During the English Revolution’. Likewise, The Experience of Defeat (1984), as Hill explained in the preface, ‘deals with ideas’. Hill’s works on individuals—Milton, Bunyan and Winstanley, with the possible exception of Cromwell—were as much intellectual biographies as they were ‘lives and times’. If we follow Hill’s reasoning that the seventeenth-century Bible was as close as there was to a ‘Jean-Jacques Rousseau or Karl Marx of the English revolution’, then even The English Bible and the Seventeenth-Century Revolution (1994) must be read as at least partly an intellectual history.

Front Cover to the 1995 paperback edition of Christopher Hill’s The English Bible and the Seventeenth-Century Revolution (Penguin, 1995).

There is an important reason for this. It is a much vaunted truism that English Marxist history was a uniquely non-doctrinaire and therefore a non-economically deterministic phenomenon. This was, however, more than the result of the latent Methodism of Hill’s youth, or those of E. P. Thompson (1924–1993) and Sheila Rowbotham (1943–present). The reaction of Hill and other English Marxist historians to what appeared to be a new ‘Stalinism’ in the 1950s was to embrace what Thompson termed ‘socialist humanism’: a humane socialism that focused on individuals as subjective agents. ‘History from below’ was one aspect of this, and Hill’s ‘worm’s eye view’ did as much as anything else to establish this practice.

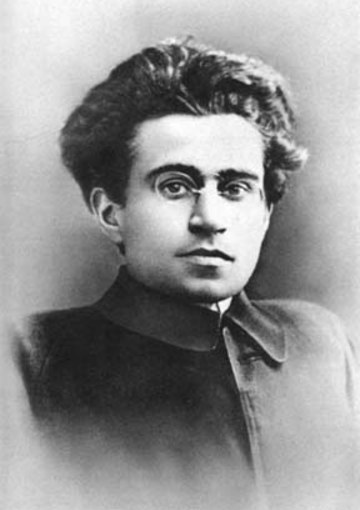

How did Hill access ordinary experiences of alternative political, religious and social traditions? Hill wrote, in a review of the first English translation of parts of the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci’s oeuvre, that ‘any man is an intellectual to some extent, even though he does not occupy the social position of intellectual; just as any man can fry an egg, though few are professional cooks.’ He wrote a history of what in Gramscian terms were the ‘organic intellectuals’ of a subaltern group. Ideas were the way to access the material and experiential reality of his subjects.

Photograph of Antonio Gramsci in the early 1920s

Hill used the ideas of ‘the meaner sort of people’ as the lens for his history. He wrote that:

Revolutions are not made without ideas, but they are not made by intellectuals. Steam is essential to driving a railway engine; but neither a locomotive nor a permanent way can be built out of steam. In this book I shall be dealing with the steam.

For Hill, the dialectic between the historical material reality and the consciousness of it through the medium of ideas is inseparable. If the train stopped moving, the ideas or the experience would dissipate. Without the ideas, the train could not move. Ideas and ‘base’ cannot be treated sequentially or without each other. Of his historical subjects, Hill wrote that ‘like maxims in philosophy for Keats, Puritanism was valid for them only when they felt it on their pulses.’

Even if Hill’s interpretation of the English revolution has fallen decisively from favour, perhaps his greatest legacy is this plea for total history: to remind intellectual historians to take seriously the ideas of ‘masterless men’ and their equivalents, and to remind social historians of the reality and importance of ideas.

Joseph Hettrick is reading for the MSt in Intellectual History at Wadham College, Oxford.

Follow us on Twitter @OxfordCIH