Defining the History of Political Thought: An Early Modernist’s View

Quite a long time ago now, I was asked to write a history of political thought in the sixteenth century (forthcoming 2021). I agreed with what now seems rather naïve enthusiasm – for, as I began to sketch it out, I realized I needed first to figure out what ‘political thought’ might mean, in a way that made sense to early modern writers but that also speaks to us now, as contemporary readers. For this is not just a question of scholarly parameters. How we define the ‘political’ matters; and how – or indeed if – we see it fitting within the broader umbrella of intellectual history will both reflect and shape our own current concerns.

For me, the history of political thought is about exploring the different ways people in the past understood and analysed their local, earthly community. It focuses on texts and writing about a specific kind of human society, one that extends beyond the family or kinship group but which is still geographically bounded. It is also one whose purposes can be fulfilled in this life, rather than the life to come or the spiritual realm. In other words, political thought examines communities other than families, empires and churches; and it emphasises earthly, interpersonal dynamics rather than questions of ethics, honour or salvation.

'The Four Philosophers', Peter Paul Rubens (1611-1612)

My purpose in defining political thought in this way was not to cut the history of political thought off from other strands of intellectual history, however. Instead I wanted to explore its distinctiveness within that broader field. In my own account of political thought in the sixteenth century, I sought to place it within the broader systems of ethics, law and religion familiar to contemporaries. But borders are often porous, and one of the themes of my book has been how boundaries were created around the political community, boundaries which separated church from state, which divided one political community from another, or which demarcated the space for individuals and families within the city. By emphasising what early modern people thought a ‘political’ community was, my aim has been to show how the history of political thought can both benefit from, and remain distinctive within, the wider field of intellectual history.

One advantage of this view of political thought is that its historian can draw on the writing of a wide range of scholarship, particularly recent work on international relations, on early modern ethics and religion, and on the family. All political communities will be shaped by wider laws and norms which are understood to apply beyond the local, to all human beings for example, or all members of a faith, or perhaps to all parents and spouses. The study of those wider principles, in the present and in the past, is an important resource for political thought, but it is different from it. Other strands of intellectual history have their own identity. At the same, what was striking for me in writing the book was how often early modern writers concentrated on the interplay between the local and the universal, the spiritual and the earthly, as they sought to understand their own political societies.

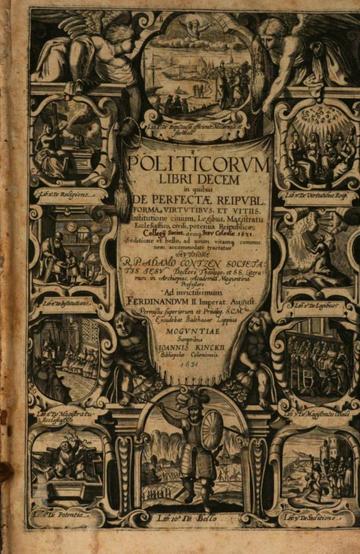

Frontispiece to Adam Contzen, 'Politicorum libri decem' (Kinckius: 1621)

Is this view of the history of political thought an early modern one? In some ways, I am sure that it is. The sixteenth century began with the rise and expansion of empires, and the interest in particular, regional communities was often a response to the perceived exploitation and injustice of empire. Furthermore, the deepening religious divisions prompted writers to focus intently on the relationship between civil and spiritual authorities, in order to understand the scope but also the limitations of politics. And the economic growth of the period (along with the development of military technology) had wide-ranging social and political implications, leading to some innovative discussions of sovereignty, of the state’s internal structures and mechanisms of reward and punishment. These themes were common across Europe, but similar ones can also be seen in Islamic world – especially the challenges of empire and economic change.

But this approach to the history of political thought may speak to broader concerns, shared by other periods and still visible in our present. The nature and the authority of the local, political community remains contested, at national and regional level – recent debates about Brexit and Scottish Independence are only two obvious examples. And human beings continue to hold values beyond or outside the scope of earthly institutions, which nevertheless impact upon our common life. Working out how (and, perhaps, whether) to allow for such values without destabilising our earthly institutions has generated important scholarly debate well beyond the early modern period, and remains a pressing question in liberal democracies.

If past histories of political thought tended to focus on the state and on those canonical figures who theorised it, future histories may take both a broader and a narrower view. By exploring the nature and the boundaries of the local, earthly community, they can maintain the separate identity of the history of political thought within intellectual history. But every boundary has more than one side, and the ‘political’ can only be understood in relation to those alternative communities which matter just as much to human beings: communities defined in terms of shared ideals, shared humanity, or even our shared existence with nature on planet earth.

Sarah Mortimer is Associate Professor of Early Modern History and Fellow of Christ Church, Oxford.

More from the Blog

Follow us on Twitter @OxfordCIH