Ethics and Equality: The Remonstrant Vision of Church and Society

Religion must be freely chosen, it must ‘proceed from a free mind’. So claimed the Dutch Remonstrant theologian Simon Episcopius in 1629, writing in France after his expulsion from a country otherwise known for its tolerance. The Remonstrants insisted that people must choose for themselves whether to obey the teaching of Christ and to follow the ethics which he revealed, for only then could a just God reward them with eternal life – or punish them with damnation. Theirs was a strongly individualistic and moral account of religion which emphasised the equality of Christians and the centrality of the Scriptural text, rather than clerical authority or Church tradition. And it proved highly influential, shaping the intellectual landscape of early modern Europe.

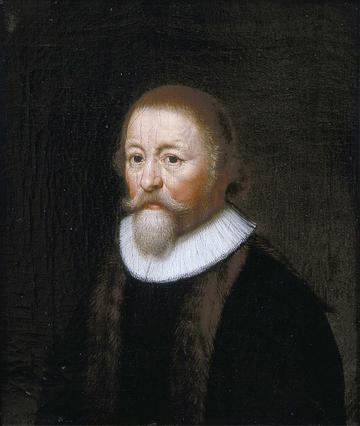

Simon Episcopius (1583-1643)

Initially this reading of Christianity was seen as extremely dangerous, seriously destabilising the Protestant account of religious and political authority. Through the 1610s the Remonstrants were attacked by their Calvinist opponents, and in 1619 they were forced into exile after the Synod of Dordt. Expelled from their home, they sought refuge across Northern Europe. From political defeat arose a new movement which emphasised individual Christian morality and a Christian community independent of the state. These ideals spread, and in Hugo Grotius and John Locke they found sympathetic conversation partners. Like Grotius, they found in Christ’s teaching – especially the Sermon on the Mount – an ethic of charity whose relationship to the demands of political life and magistracy was far from straightforward; discussions over the meaning of Christ’s warnings against violence and lawsuits were an important context for Grotius’s masterpiece, The Rights of War and Peace (1625). Later in the century, Locke drew upon Remonstrant ideas in advocating toleration, education, and the duties of human beings – he even dedicated his Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) to the Remonstrant Philip Van Limborch.

By the later seventeenth century Remonstrant writing was widely distributed across Europe and it soon became a crucial strand of the early Enlightenment, especially in the Netherlands and England. Some editions were reprinted in London and most Oxbridge college libraries have multiple copies of Remonstrant works. Yet the Remonstrant movement has long been neglected by historians – their long Latin folio volumes were designed to be accessible for seventeenth-century readers, but today seem more forbidding. Meanwhile, their combination of intensely Scriptural theological scholarship, political reflection, and ethical exhortation doesn’t map neatly onto contemporary disciplinary boundaries or concerns. But if we want to understand early modern intellectual history, especially the emergence of Protestant natural law thinking, then we need to take their contribution seriously.

As important as the Remonstrants’ ideas were their efforts to create a distinctive kind of Christian community, held together through print and through writing. This was a community forged through exile, stripped of the power and privileges of the Dutch Public Church, and sustained by their shared understanding of the scriptural text. Although many Remonstrants returned to the Netherlands from the 1630s, they were not allowed their own public buildings and they retained their distinctive understanding of the Church. What they had was a Seminary, led initially by Simon Episcopius who had been their chief spokesman at Dordt. In this situation, their emphasis on the Scriptural text became a wider commitment to the centrality of words and persuasion. By the 1680s, Van Limborch was particularly keen to promote ‘parrhesia’, candid and open speech directed to the common good, and this concept had become central to their identity.

Philip van Limborch (1633-1712)

Such a strongly textual community was created and sustained in large part by letters and through the careful curation of printed texts, particularly by the indefatigable Van Limborch. Here readers could find a vision of Christian society in which freedom of worship and of thought was not only allowed but explicitly encouraged. Rather than offer one single, unified theology, Remonstrants published works which included discussion from multiple viewpoints, at least where they believed there were grounds for legitimate debate (such as over the legitimacy of serving as a magistrate). The letters in particular drew together leading theologians from the Remonstrant movement and beyond, suggesting a vibrant and courteous conversation about the meaning of the Scriptural text. And yet, within this community new hierarchies emerged and new practices of exclusion developed. Their writing was fiercely anti-Catholic and their emphasis on scripture and erudition led them to prioritise a particular kind of Protestant learning only accessible to educated and elite men. Faced with Quakers and Collegiants who appealed to the ‘light within’, the Remonstrants became ever more insistent on the need for scholarship and study.

Over the next few years, I will be writing a new account of the Remonstrant movement (and I am very grateful to the Leverhulme foundation for a grant to enable some research leave next year). By studying the Remonstrants’ practices as well as their texts, I will reveal the efforts of the community’s leaders not only to theorise a new church but also to live it, in the real world. And I will show how they shaped the early modern ideas of politics and Christianity whose legacy remains with us today.

Sarah Mortimer is Professor of Early Modern History at Oxford and Tutor at Christ Church. Her most recent book is Reformation, Resistance and Reason of State: The Oxford History of Political Thought 1517-1625 (2021).