Gibbon and the Islamic Orient

The historian of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon (1737-94), has been treated by some postcolonial scholars as a typical western Orientalist. Edward W. Said (1935-2003) critiqued Gibbon in his seminal polemic, Orientalism (1978). This book essentially argues that as far back as the late seventeenth century, European culture and scholarship has treated the East/Orient (basically defined as Asia, North America and the Middle East), its peoples, cultures and religions, especially Islam, as inferior, different and something to be feared, stereotyped and/or ridiculed. For Said, this approach is pervasive in the West’s imagination of the East more broadly.

Edward Gibbon by Joshua Reynolds, 1779. Bridgeman Art Library.

To an extent, Said is perhaps correct: the impression of an early interest in the magical nature of the East, rooted in the neverland of the Arabian Nights, where time stands still in an exotic locale, appears in parts of the Decline and Fall. The appearance of a stereotype is not infrequent. In his pages on the General Consequences of the Crusades, Gibbon concludes that Muslims had “primitive manners” despite their encounters with Westerners. Muslims here are depicted somewhat like Montesquieu’s Muslim character Usbek in the Lettres Persanes (1721), who reigned as a tyrant over his wives in the seraglio despite many years spent in western Europe. Gibbon, somewhat like Montesquieu, avers that European manners invariably supersede those of the Islamic Orient.

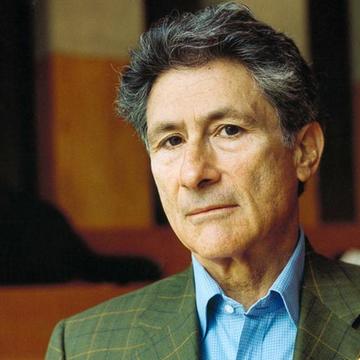

Edward Said, Picture Alliance, 1999.

But whereas Gibbon may at times be guilty of infusing his writings with a self-serving happiness of the culture of his eighteenth-century present, it is wrong to paint him with a single brush. Gibbon tempered the fantastic and wrote a history of the East which is unquestionably human. He endeavoured to be objective and treat the East on equal terms. For example, he called Voltaire a “bigot” for praising a Muslim Sultan’s decision to abdicate in favour of a contemplative life, when Gibbon says, Voltaire would not have praised a Christian prince for retiring to a monastery.

Gibbon had early interests in the East. He was an avid reader of the Arabian Nights as a schoolboy. Dr Johnson called Gibbon a “Mahometan in his youth”. When he matriculated at Magdalen College, Oxford, Gibbon planned to study Arabic, but was discouraged by his tutors, and went on to have a miserable time at the college, viewing his tutors as sunk in port and prejudice, occupying their time with little more than Tory politics and private scandals.

Gibbon’s history of the East is interesting and did not presuppose European superiority, unlike, perhaps, some of his contemporaries, such as William Beckford (1760-1844), a man whom Gibbon detested, and who wrote the Orientalist fantasy novel Vathek (1789).

A key theme in volumes five and six is of Islam as a humane religion, enabling the flourishing of human potential. During Mahomet’s conquest of Constantinople, the “gold and silver, the pearls and jewels, the vases and sacerdotal ornaments” of the cathedral of Saint Sophia “were most wickedly converted to the service of mankind”. Gibbon’s irony here captures his distrust of Christian priests but more strikingly denigrates the failure of the remaining Roman empire to use its material riches for human beings. The Muslim conquerors are praised, essentially, for their rationality; the fulfilment of Gibbon’s philosophy, where reason triumphs over blind faith.

Elsewhere in the Decline and Fall, Gibbon depicts the “carnal paradise” of the Muslim heaven as resurrecting the human body “to complete the happiness of the double animal, the perfect man”. A more sexually active and liberated East is presented favourably. To an extent, one can read this as Gibbon preferring to keep sexuality at a distance, writing about it in the past, so that he can remain a spectator to the affairs of the human body.

But it fundamentally demonstrates that Gibbon praised the East, not as a space of the licentious, but as a space free from the monkish virtues which suppress the vitality of mankind. Gibbon here writes as a philosophe, actively seeking to present the objective reality and greater humanity of the medieval Orient.

Gibbon’s view of European-Oriental relations is clear, moreover, when he chastises the west for not appreciating their experiences with the east. In chapter sixty-one, he writes:

“Among the crowd of unthinking fanatics, a captive or a pilgrim might sometimes observe the superior refinements of Cairo and Constantinople: the first importer of windmills was the benefactor of nations; and if such blessings are enjoyed without any grateful remembrance, history has condescended to notice the more apparent luxuries of silk and sugar, which were transported into Italy from Greece and Egypt.” And in the footnote, he observes that windmills “first invented in the dry country of Asia Minor, were used in Normandy as early as the year 1105.”

Windmills are a form of technology with peculiar importance here. The Orient provides the west with an advance in trade and manufacture, and thus economy and civilisation, but it has collected no noticeable appreciation. “History”, by which Gibbon seems to mean the western writing of history, has chosen to remember luxuries instead. Thus, Gibbon castigates the Latins for their ignorance, failing to remember the greater value of windmills and prioritising mere luxury.

One is tempted here to imagine Sancho telling Don Quixote that what he sees are not giants but only windmills. We know that Gibbon was familiar with Don Quixote from chapter twenty-eight where he compares Martin, bishop of Tours with Miguel de Cervantes’ knight in order to chastise the bishop for being part of the fourth-century clergy’s “destructive rage of fanaticism” in destroying old pagan temples.

Don Quixote and Sancho Panza by Jules David. 1887.

In chapter sixty-one Gibbon presents “unthinking fanatics” and “windmills” in the same phrase and in the case of both the windmills and the old pagan temples, a physical structure is denied its rightful place in history by the vanity of new, ignorant rulers: the temples were no longer used in the service of idolatry, there was no need to destroy them. Martin of Tours is compared with Don Quixote mistaking an innocent funeral for an idolatrous ceremony and he ‘imprudently committed a miracle there’. This false action becomes in the Asian windmills how the west has been blinded by desires to appear important, eschewing its true and useful inheritance. We cannot be sure if Gibbon meant this comparison but nonetheless the poignancy with which he deploys windmills as a technological advancement, whether with the Quixotic interpretation or without it, reduces the dignity of the western culture, creating a favourable image of the Muslim east.

Finally, Gibbon’s history of the East entertains his reader with a rich domestic texture. Gibbon was himself a domestic creature, from his early life at Buriton where he valued the “supply of the kitchen much more than the exercise of the field” to his retirement in Lausanne where he entertained guests and meticulously managed his household inventory, especially the supplies of food and wine. He enjoyed writing about Eastern society with interest, humour, and occasionally admiration. For example, the caliph Soliman died of indigestion and in the footnotes, Gibbon comments on an extravagant meal which Soliman ate on one of his pilgrimages to Mecca, “If the bill of fare be correct, we must admire the appetite rather than the luxury of the sovereign of Asia”: an amusing example which completes the history of the caliph’s life with gentility and goodness. Soliman’s gastronomical brilliance thus supersedes in the reader’s imagination the political consequences, the “fatal and irreparable loss” in which his death presented the forces of the east.

Allusions to domesticity, moreover, provide comic moments, as when the Muslim spies infiltrate the “kitchen of Bohemond” during the crusades and “were shown several human bodies turning on the spit”, inspiring “terror” among the infidels. Comedy here is created by the inversion of the normal kitchen; the joke chastises the desperate vulgarity of the Europeans. The nightmare confronting the spies recalls the downfall of the house of the Ommiades during a banquet in Damascus, the seat of their overlords, when the dinner party was upended by a “promiscuous massacre” and the “festivity of the guests was enlivened by the music of their dying groans”. The cannibalistic kitchen and the murderous overture are taken from Christian and Muslim cultures and show Gibbon’s innocent playfulness rather than a sinister form of Orientalism.

This is an article based on Kieran Bailey's (BA, Oxford 2021) Undergraduate Thesis, 'Gibbon and Islam'.