How 'Chinese' is Chinese Theology? The Case of Wu Yaozong

Almost half a century after his death, Wu Yaozong (1893-1979) remains a deeply controversial figure in the history of Chinese Christianity. A prominent ally of the Communist Party after it took power in 1949, Wu is venerated in mainland China today as ‘a model of patriotism and faithfulness.’ Overseas, he is either branded a political opportunist or – in more aggressive commentaries – a heretic and anti-Christ. Yet both readings ignore the vast and sophisticated body of Wu’s theology before 1949 – when his theological mind was arguably at its best. Wu’s left-wing theology emerged as early as the 1920s and culminated in 1943 with the publication of No Man Hath Seen God. In this book – what he calls ‘my magnum opus, my most carefully crafted piece’ – Wu presents an original theological system that aims for the rapprochement between Christianity and materialism.

Reading No Man Hath Seen God has led me to believe that existing literature points us in the wrong direction for a proper understanding of Wu’s arguments. Since the 1980s, historians and theologians of Chinese Christianity have typecast the first half of the twentieth century as an age of ‘Sinicisation’ – when Chinese Christians transformed an alien Western faith into an indigenous Chinese one. On this view, scholars have proposed various theories of how No Man Hath Seen God integrates Christian theology with traditional Chinese philosophy. But a survey of the book’s text and context reveals little evidence to suggest that Wu’s theology is a product of so-called ‘Sinicisation’. Instead, it stems from the cross-cultural movement of people and ideas. No Man Hath Seen God is an impenetrable piece unless we take seriously Wu’s two main influences from the West – twentieth-century American liberal theology and Spinoza’s pantheism.

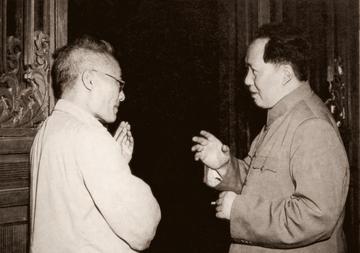

Wu with Mao Zedong, June 1950.

Wu’s interest in liberal theology began at New York’s Union Theological Seminary, where he studied on two separate occasions in 1924 and 1936. Union’s emphasis on a scientific approach to theology left a lasting mark on Wu’s mind, prompting him to write his thesis on William James’ psychological explanations of religious experience. But Union was best known as the beating heart of the social gospel movement, which sought to apply Christian principles to address the social crises of industrial capitalism. And it was during Wu’s student years that Union’s lecterns were occupied by such great names as the socialists Reinhold Niebuhr and Harry Ward. Wu’s time abroad also gave him linguistic and intellectual skills for sophisticated engagement with Spinoza’s Ethics, which he read in the late-1920s. In the preface to the 1946 edition of No Man Hath Seen God, Wu unpacks the book’s title – a quote from John 1:18 – with a Spinozist twist: even if ‘no man hath seen God’, God still exists invisibly, as the necessary and infinite substance of the universe through which everything else takes shape.

No Man Hath Seen God at once becomes intelligible if we see it as an extension of Spinozist philosophy. For Wu, Spinoza’s definition of God – a being consisting of infinite attributes from which all else flows – comprises both material and spiritual dimensions of human experience and makes it possible for Christianity to appreciate materialism. However, Wu also goes beyond Spinoza’s dictum – Deus, sive Natura – which equates God with the aggregate of natural phenomena. Wu believes this is a partial outlook, because it only captures what he calls the world’s ‘horizontal perceptive’ – the laws of its becoming, the breadth of its phenomena. What Spinoza fails to see is the ‘vertical perspective’ – the world’s essence, the depth of its being – an essence hidden, and sometimes completely different, from outward appearances. Wu then likens materialism and Spinozism: Since materialism, like Spinozism, recognises outward natural laws but denies a transcendental essence hidden beneath, Christianity – which recognises both the seen and unseen – necessarily accommodates materialism.

Baruch de Spinoza (1632-1677).

This, for Wu, does not mean Christianity is in any way superior to materialism, only that a Christian can accept everything a materialist believes. This position sets Wu apart as a radical revisionist of the liberal theology he encountered at Union. Drawing on German precursors such as Adolf von Harnack, American liberal theologians proposed a rationalist reappraisal of Christianity in response to developments in literary criticism in the natural sciences. Wu’s time at Union brought him to the fore of this developing tradition, which emphasised Christ’s role as a human teacher and interpreted miracles as metaphors. But, for Wu, American liberal theology’s attempt to adapt Christianity to rationalism is still not radical enough, because it ‘assumes Christianity and materialism are separate and opposing systems.’ In contrast, Wu begins with a more constructive spirit, actively juxtaposing Christianity and materialism to foster dialogue between them. As they interrogate and enliven each other, Wu shows that Christianity is not just uncontradictory with materialism, but also advances materialism by its unique recognition of a transcendental dimension beyond outward phenomena.

Recent scholarship in both the history of Christianity and Chinese intellectual history has turned to place Chinese thinkers within a global network of the transmission of ideas. The rise of the school of ‘world Christianity’ has called attention to how foreign missions and local churches share in a ‘worldwide consciousness’. Meanwhile, Chinese intellectual historians Leigh Jenco and Jonathan Chappell have argued that Chinese thinkers were not passive recipients of knowledge ‘disseminated’ from the West, but ‘co-producers’ with Western thinkers, conscious of their ‘embeddedness’ in a transnational community of knowledge. My reading of Wu joins a larger historiographic corrective against the cultural essentialist narrative of Chinese theologians making pristine ‘Chinese’ arguments uncontaminated by the West. But Wu’s theology can also help us bring this entire argument of connections and commonalities one step further: Wu’s critique and development of Spinozism and American liberal theology make the powerful case that Chinese theologians were not only conscious of their membership in a global intellectual community, but also fully aware of their ideas’ potential global impact, and actively sought to contribute to the advancement of humankind’s common knowledge.

So, is Wu’s theology ‘Chinese’ at all? Acknowledging Chinese theologians’ global frame of reference and authorial intention for universal appeal, I think, does not eradicate the ‘Chineseness’ of Chinese theology, but invites us to reconsider what such ‘Chineseness’ entails. Here, the intellectual historian’s textual-cum-contextual approach is especially helpful to broaden our conception of ‘Chineseness’. Even if Wu’s theological arguments are not ‘Chinese’, his historical circumstances and literary tropes certainly are. Wu’s study of Christianity’s relationship with materialism began in the 1920s, when national anger against imperialist violence was at a high point. His project to create a materialist-tolerant theology was thus a response to the needs of contemporary politics – to disassociate Christianity with imperialism and align it with the most progressive political force. Wu also deploys a remarkably wide range of Chinese literary tropes and motifs to illustrate his Western arguments. From Li Bai’s poetry to Gu Yanwu’s philosophy, from the I-Ching to the Three Kingdoms, all give No Man Hath Seen God a Chinese flavour, and make it a uniquely Chinese contribution to the universal repository of human knowledge.

Duanran Feng is an MPhil student in intellectual history at St Antony’s College, Oxford. He is interested in the intersection of Christianity and social-political thought in both China and the Church of England in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.