In Search of Zera Yacob: Philosophy in Early Modern Ethiopia

In 1852, a remarkable manuscript was discovered by a Capuchin monk in the highlands of Ethiopia. The text told of a man named Zera Yacob (1599-1692), born ‘in the land of the priests of Aksum’, educated by traditional Ethiopian scholars and ferenj [European] missionaries and driven from his home by the conflict that broke out between the two groups. Fleeing in the night he made for the wilderness, and near the banks of the Takkaze river found refuge in a remote cave where he ‘meditated all day on people’s quarrels and wickedness, and on the wisdom of the Lord their creator, who keeps silent when they act wickedly in his name’.

In this cave the exile produced a philosophical system of exceptional depth and originality, grounded in an account of a universal faculty of lebuna—reason, understanding or intelligence—which allowed every human being to reflect on the world and its creator, and to literally see the difference between truth and falsity, good and evil. This faculty was divinely endowed, a product of a pre-ordained harmony between creator and creation: ‘the creator put in the heart of humans the light of intelligence, that they may see good and evil; recognise what is and is not their duty; and distinguish the truth from a lie’.

The philosopher constructed arguments for the existence of God, elaborated a theodicy, and harshly critiqued what he saw as the corruptions of organised religion: of Orthodoxy, Catholicism, Islam and Judaism alike. In his later years, having descended from the cave to live a simple life in the town of Enfraz, the philosopher gained a disciple, Walda Heywat, who encouraged him to write down his ideas, and who would develop his thought into a system of social ethics in a companion treatise, the Hatäta Walda Heywat.

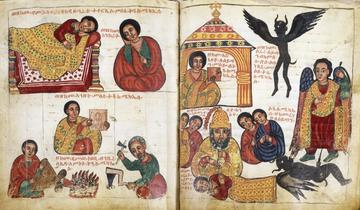

Manuscript illuminations in the ‘Gondarine’ style, late 17th century.

At the same time that Zera Yacob was meditating in his cave, another more familiar seventeenth century philosopher, René Descartes, conducted his own set of solitary meditations on God, reason and the basis of knowledge. The contemporary emergence of these set of reflections in France and Ethiopia have struck many commentators; in the words of one historian serves to demonstrate that “modern philosophy, in the sense of a personal rationalistic critical investigation, began in Ethiopia with Zara Yacob at the same time as in England and in France”. Why then, have so few of us heard the name of Zera Yacob?

The answer lies in the nineteenth century discovery of the manuscript, and the subsequent reception history of the text. The Capuchin monk who discovered the manuscript—Giusto d’Urbino—was tasked with collecting rare and unusual manuscripts by Antoine d’Abbadie, an Irish-Basque explorer, geographer and the head of the Académie des Sciences in Paris; after the death of A'bbadie the works were donated to the Bibliothèque Nationale. In the first years of the twentieth century, scholars who examined this unprecedented collection were struck by this unique work. In just a few years two critical editions from Boris Turayev (1905) and Enno Littmann (1909) were published, and translated into Latin and Russian respectively, becoming the object of significant attention in scholarly circles.

Turayev and Littmann themselves took the work seriously as a work of philosophy, appending short expositions of their own, and while both saw outside influences in the work—Littmann discerning the influence of early Islamic kalam on Zera Yacob’s cosmological argument, and Turayev intriguingly suggesting an analogy with the English deist Herbert of Cherbury – both considered the Hatäta to be a fundamentally Ethiopian text.

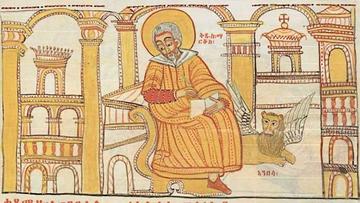

Opening to the Gospel of St. Mark, Gondar, Ethiopia, 1664-1665.

But just as the Hatäta was gaining broader interest, in 1920 an article appeared in the Journal Asiatique by the Italian orientalist Carlo Conti Rossini, arguing that the work was a forgery, whose author was none other than its the supposed discoverer: Giusto d’Urbino. Conti Rossini’s argument was full of philological rigour, but also cultural speculation:

Ideas as those of Zera Yacob would not be expected in Ethiopia, where blind faith and byzantinism of the interpretations of the Holy Scriptures seemed to oppose an insuperable barrier to free thinking, whose blossoming over there we would not even know, as it were, how to imagine.

While Turayev and Littmann tried to account for this singularity by identifying external influences, Conti Rossini claimed that the text could only come from outside the Ethiopian tradition entirely, from the influence of a more ‘civilised’ agency. Real philosophy, he suggested, was impossible in Ethiopia. This explained how the text appears to anticipate Enlightenment ideas or to mirror Descartes: the true author of the text had read them in nineteenth century Europe. Eventually scholars in the burgeoning field of Ethiopian studies became convinced that the work was a forgery. A new consensus was established and the Hatäta fell into obscurity.

Henry Salt: The Obelisk at Axum.

The answer, then, to why you have not heard of Zera Yacob is that he did not exist. The Hatäta is not the first work of ‘African philosophy’, not the ‘jewel of Ethiopian literature’, but an intricate and elaborate forgery, by a lonely monk in a foreign land.

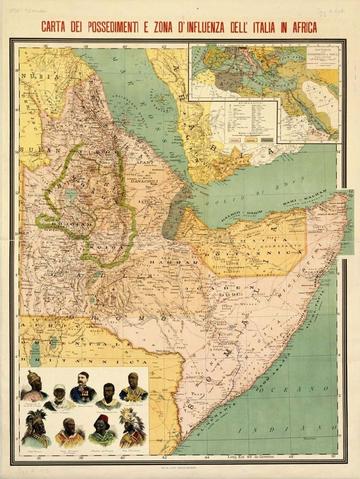

Or is it? Conti Rossini was not only the pre-eminent scholarly authority of East Africa, but between 1899 and 1903, also a colonial administrator in Italian Eritrea. In the early thirties he published, an article arguing that Ethiopia was incapable of civilisational progress, and that it therefore could, indeed should, be colonised by a ‘civilising’ power. It formed part of a coordinated programme of fascist imperial propaganda in the sciences and humanities, and in 1937, midway between the Italian conquest of Ethiopia and the beginning of WWII, Conti Rossini received the Mussolini award from the Accademia Nazionale delle Scienze, for his services to ‘history and moral sciences’.

The cultural politics of the debate would be reversed half a century later when, during the period of the decolonial reassertion of an indigenous African intellectual heritage, a number of scholars took up the question of authorship once again. The Ethiopian scholars Amsalu Alkilu and Almeyahu Moges pioneered arguments grounded in a deep knowledge of Ethiopian educational traditions, suggesting that the forms of biblical quotation demonstrate that the author was educated in traditional Orthodox schools. Claude Sumner, in his monumental five-volume Ethiopian Philosophy (1974-8), offered rigorous statistical analyses of sentence and paragraph length and comparative philology between the Hatäta and d’Urbino’s other works, claiming to demonstrate that the work could not possibly have been forged by d’Urbino.

Map of Italian colonial possessions and zone of influence in East Africa c.1896.

The authorship debate today still rages. Opinions are polarised: among recent publications, the late, eminent scholar Getatchew Haile argued for the Hatäta's authenticity, while a seminal series of articles by Anaïs Wion argued the case for forgery. Ongoing work, including a new translation by Ralph Lee, Wendy Belcher and Mehari Worku and an edited volume from Jonathan Egid, Fasil Merawi and Lea Cantor will provide yet new perspectives on the Hatäta.

Whoever the author, the Hatäta is a most remarkable document: a profound work of philosophy, an anguished reflection on political and religious strife and a compelling narrative of a life in thought. If its author was indeed a seventeenth century Ethiopian, our understanding of the development of modern philosophy will be changed in radical ways. If its author is a nineteenth century Italian monk, it is one of the most remarkable literary forgeries ever created. By now scholarship on the Hatäta has expanded far beyond the authorship debate to include examinations of the philosophy, style and subsequent impact of the text, regardless of the author, and the broader cultural significance of the work.

A forthcoming conference at Worcester College, Oxford, organized in collaboration with Philiminality will examine the ideas, language and history of the Hatäta Zär’a Ya‛ǝqob by bringing together scholars from across the world, and across disciplinary boundaries. It aims to stimulate a productive dialogue between scholars from philosophy, history, philology, and Ethiopian studies, and to serve as a prolegomenon to broader philosophical study of the Hatäta, bringing these remarkable works, and the world they describe to the widest possible audience.

Jonathan Egid is reading for PhD in Comparative Literature at King’s College London. To find out more about the upcoming conference click here.