Intellectual History at the End of the World?

'In a few short centuries, the human species has begun unmaking the balance on earth between life and death, enabling death to expand and expand, tilting life towards a catastrophe that is difficult to imagine, difficult to think, and yet morally imperative to consider'.

Deborah Bird Rose, Wild Dog Dreaming: Love and Extinction (2011).

What is the future of intellectual history? The question is asked as the planet heats; permafrost melts; oceans rise; weather becomes more extreme; toxic chemicals and plastic pollutants contaminate sea, earth and air; millions of species face displacement and extinction, and experts warn of the growing risk of the collapse of human societies.

The pursuit of intellectual history may seem a perverse indulgence in such times, but this would be to surrender to the narrative that marginalises humanities in favour of STEM and eschews analysis of the roots of our condition in favour of ‘solutions’. The devastation of our planet is entirely anthropogenic in its causes. It is a product of particular trajectories in human thought and the systems, structures, ideologies and inequalities that produced them and that they have engendered. This means that intellectual historians are uniquely well positioned to trace how the current situation has come about. Not only this, we should be able to illuminate the issue of why so little is being done to prevent the most alarming scenarios becoming fact when, globally, dominant epistemologies would seem to place the authority of the sciences at the heart of policy.

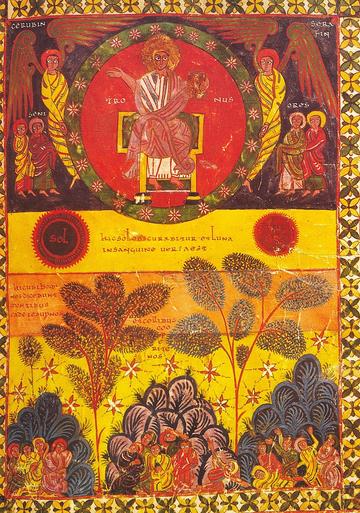

Opening the sixth seal of the apocalypse: ‘And the kings of the earth, and the great men, and the rich men, and the chief captains, and the mighty men, and every bondman, and every free man, hid themselves in the dens and in the rocks of the mountains’ – Morgan Beatus, C10th (Pierpont Morgan Library, Ms 644, f°112).

Doing so in ways that might yet be fruitful at this late stage will involve recognition of the complicity of the discipline in this situation. For decades, historians studying the ‘great thinkers’ of the (mostly, western) past used a conceptual framework and language of renaissances, enlightenments, intellectual developments, advances in thought and technology, and the triumph of humans over nature. It was a teleology that allowed for unevenness, for dark ages, but discerned these by means of an implicit value system: a sense of what forward momentum looked like. This has been, and remains despite the mounting evidence to the contrary, the single most influential interpretation of human activity in recent millennia. It stands between westernised societies and the necessary recognitions that might yet prevent civilizational collapse. It gives ideological cover to terrifying ‘climate solutions’ such as geoengineering earth’s atmosphere as well as to continuing investment in the panoply of ill-considered human ‘advances’ that are driving ecological devastation. It serves a contemporary politics that resists disruption to the status quo regardless of cost to future generations. It is one reason for the phenomenon discussed by Amitav Ghosh in The Great Derangement (2016): the climate crisis is ‘also a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination’. That a valorisation of human mastery might make it very hard for humans to grasp the costs and realities of behaviour coded as mastery is an interesting problem for those who study ideas and their effects. Plenty of work in the history of thought and adjacent fields seeks to problematise, unravel and rewrite this grand narrative, but it is a tricky enterprise, requiring humility, caution, flexibility—and a belated recognition of how existentially ill-equipped we are to comprehend the overwhelming complexity of earth’s intricately interconnected systems.

Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (ca. 1412-16) – month of March.

For intellectual historians working on questions around how we arrived in a place of rupture between deeply inhabited ideas and ‘difficult to think’ realities, it can be an enterprise against the grain of the field, even against its familiar language and conceptual tools. Looking back over the centuries, it might mean reimagining ‘developments’ in thought as, instead, processes by which communities were directed away from knowledge of how to live in particular places, while localised epistemologies of that life were dismantled and replaced. These processes seem to have been integral to state—and civilisation—making for thousands of years, as ‘barbarians’ were tamed, ‘pagans’ converted, and ‘primitive tribes’ educated into the ways of their colonisers. The ecological cost, as well as the human, was often high. Landscapes were ‘cleared’ and marshlands ‘reclaimed’ for monocropping, which in turn rendered soils unfertile, crops less healthy, and transformed other plants, insects and animals conceptually into weeds and pests requiring and deserving eradication. Disturbingly, the rooting up of complex ecosystems, the ploughing of the bared earth, and its seeding with grain to swell the lord’s granary was also used from the early medieval period in the west as a metaphor for ‘enlightening’ and governing human populations. Those who challenged the simplifying doctrines of a church that preached transcendence of messy embodied finite life and planetary boundaries, were spoken of as weeds, thorns, foxes and locusts. By the central middle ages it was the duty of those tending the lord’s vineyard to call for their extermination. Ecological simplification and the simplification of human thought and relationships were conflated into a single salvific project for the ordering and improvement of the world.

‘God the Geometer’ – creating the universe on the basis of geometric principles – from the Bible moralisée, ca. 1220-30 (Codex Vindobonensis 2554, f.1 verso).

Simplification has often been the goal of ‘advances’ in thought: bringing the ineffable and indescribable within the compass of human comprehension. States, as much as churches, desired to make their resources and their subjects legible. Perhaps to serve these ends, the intellectuals whom they approved often sought to create bodies of knowledge envisaged in universal terms, measurable and replicable. What good could local and situated perspectives do, after all, but foster a kind of ungovernable illegibility? The wilderness has mostly been disregarded as a site of possible knowledge; it is only part of the story when its usefulness is attested by civilisation. What many indigenous populations have known continuously, westernised science first violently denied and is now stumbling to discover and describe, increasingly by seeking out the help of members of those damaged communities. But it still prefers to have indigenous skill in nurturing biodiversity ‘simplified’ by being stripped of its ontologies, its earth beings and its Dreaming – even though it is very doubtful that skill and stories are separable. Similarly, the idea of ‘rewilding’ is troubling to many because it unpicks the old imperative to render land ‘productive’ (to humans), and suggests that ecosystems recover and function better when left alone. What truths does this tell modern westernised humans about their mastery? What—if one cared to see it in such terms—aare the challenges and ambivalences for historians of attempting salvage from the wreckage piling at our angel’s feet?

Ausangate, the mountain in Peru that is also an earth being, involved in the legal defeat of the hacienda and the return of the land to the people connected to it.

Some help might come from Marilyn Strathern’s much quoted formulation: ‘it matters what ideas one uses to think other ideas (with)’—or as she puts it elsewhere: ‘possibilities are imagined through ideas already in existence and already part of a cultural repertoire’ (Reproducing the future (1992)). Given the overwhelming scientific consensus around the deteriorating conditions within which the human future must take place, unless one chooses nihilism or denialism, ideas seem to matter more than ever. It is, among other tasks, the business of intellectual historians to shed light on the pasts of the ideas that are now being used to think the future. It is also a good time to make space for, support, reflect on, seek out, and where necessary, recover, other ideas and ways of thinking that have been lost or side-lined along the way. The rapid expansion of the subjects and perspectives of intellectual history in recent decades lends itself well to a wider view of what intellectual history might encompass if it wished to tell a different story of human thinking. Beyond this, do almost unthinkably radical possibilities beckon? If scientists are finding intelligence in plants, memory and communication through mycorrhizal networks; if anthropologists are discovering thinking in forests and finding ways to talk about the intentions of mountains, what might intellectual historians come to include within histories of thought?

Amanda Power is Sullivan Clarendon Associate Professor in History and Sullivan Fellow at St Catherine’s College, Oxford.

More from the Blog

Follow us on Twitter @OxfordCIH