Late Medieval Europe: Founding a Parliamentary Culture

Is there any such thing as a parliamentary culture in pre-modern Europe, before Thomas More’s England, before the great Polish Sejm held at Radom in 1505 or before the revolutionary States General in the sixteenth-century Low Countries? Admittedly, the first laid claim to free speech in the House of Commons, the second was granted the privilege of common consent and the third ousted a king and founded a republic. Such significant advances, however, were not and, indeed could not, be born from scratch. They belonged to a recognizable form of parliamentary culture, a transnational inheritance of ideas melting into a common European tradition. As such, they rested upon an age-old culture, or rather a mix of common practices, pertaining to such multifarious spheres as voting patterns, petitioning cultures, assembly practices, altogether embedded in nascent legal frameworks, ideological representations of society and the rise of the Modern State, from the thirteenth century onward, if not even earlier.

A king of Aragón, probably Jaume I (1208-1276), holding a parliament in Catalonia. This schematic representation was imagined in the late fifteenth century. Archivio de la Corona de Aragón, Incunable 49, fol. 34v. Wikimedia Commons.

The history of medieval representative assemblies is largely dominated by a functional paradigm that tends to emphasize the study of their role in the institutional development of the states and principalities that were being formed during the closing centuries of the Middle Ages. This role was twofold: first, submission by the people of a number of grievances in the form of petitions or supplications, to which princes were requested graciously to respond; and second, the granting of extraordinary fiscal resources that princes could not reasonably obtain without the consent of their subjects so assembled. Medieval assemblies have been thriving, under different names (parliaments, states general, cortes), throughout the Latin Christian world, from Poland to Portugal and from Scotland to Sicily. They originated from ancient feudal, and highly ceremonial, gatherings such as public crownings or solemn judicial sentencings, often staged in ecclesiastical settings such as general councils, from where they migrated to secular polities from the thirteenth century onward. It has been stressed that such assemblies could not by any means be deemed constitutional, nor could they be considered representative in a modern sense.

Nevertheless, and this is a key figure of early medieval political assemblies, they foreshadowed future developments of representation, inasmuch as they acted as impersonations of political communities, equating ritually formalized bodies to the featuring of the entire community of given regnal or seigneurial entities. One landmark of this evolution was the admittance in such bodies, at a fairly early stage, of subjects beyond the traditional elites of lay and clerical aristocracies: knights of the shire in England, and local magistrates of cities, towns and boroughs in continental Europe, which, in some places, included guild craftsmen. Initial steps toward institutionalization followed, through the election of members, through the crafting of cautiously worded proxies, through the allocation of rights to seat, through the granting of special safeguards to such participants. All in all, though immensely variable in such a vast array of polities, these steps led to what might be the most significant contribution of medieval assembly practices to the modern parliamentarian culture, that of the symbolization of a community through a body empowered to effectively and legally bind each and every member of these communities to the decisions enacted in their name. Such wordings as « the community of the realm » in England, assemblies « constituting and representing the three estates » in France or the « general of the land » in Catalonia, all in their own way, tend toward a more accurate expression of this new political abstraction, that of a people simultaneously created by and empowered through its’ own representation. This cultural accomplishment clearly epitomizes what John Austin defined as performativity, as the art of doing things with words by following general principles of time, place, authority and so on. More generally, it rests on a number of legal fictions typical of a widely, albeit at times diffuse and ecclesiastically mediated, tradition of Roman legal culture: the general principle according to which what concerns everybody must be approved by everybody, the general standards of elections and voting through the rising practice of strict majority rules, forcing, in turn, the recognition of the fundamental equation of the democratic mind: that the majority’s will perfectly enacts the general will.

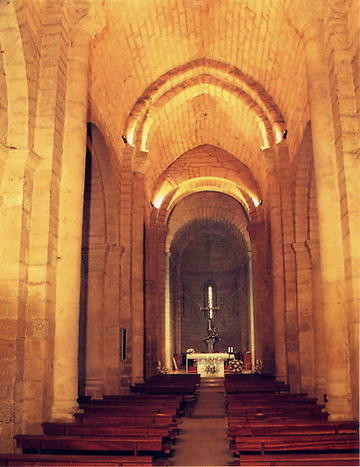

Monzón’s Santa Maria cathedral was a famous meeting-place for the general cortes of the Crown of Aragon, although its’ architecture appears to be less than ideal for the seating of numerous members of the different orders of society. Photograph by Michel Hébert.

A central feature of medieval parliaments – or pre-parliaments, as they should rather be called – is their dependence on regal or princely authority. As G.O. Sayles bluntly put it many years ago, the medieval English parliament is clearly the “king’s parliament” and, across continental Europe, assemblies hinge upon princely authorizations to be convened. Numerous attempts to gain rights of self-summoning, for instance, were met with unwavering opposition; and princely presence, in formal wear and dominant seating positions, was required in order to legitimate words pronounced and deeds enacted in such solemn venues. Unsurprisingly, the symbolic features of such gatherings prevailed in every aspect of their celebration. Choosing the meeting-place, whether political capitals-to-be (for the grandeur of the settings), or remote localities (for the controllable accommodation of participants) was an important issue for kings and princes, whereas selecting apparently independent premises, especially convents of the mendicant orders, appeared to be the best option for the separate sessions either of the Commons in England, or of the different orders of society elsewhere. Uses – and misuses – of language, whether in the solemnity of opening sessions or in the less formal convenings of different working groups, followed accordingly standardized rhetorical practices. Orders of seating, with the intensive use of various features of geographical positioning in fenced spaces, conditioned corresponding precedence in the right and the order of speaking, thereby granting varying levels of authority to strictly hierarchized social strata. Nonetheless, such gatherings, however loosely institutionalized, through the “chafing of mind against mind”, as English historian Maude V. Clarke once put it, clearly contributed to the formation, the expression and the acknowledgment of political consensuses strong enough as to lay the groundwork for contractual, if not yet constitutional, forms of state-building. Such combinations of functional practices and symbolic features, whereby the emerging states were “visibly manifested” as political bodies, the “emperor’s old clothes”, as Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger aptly put it, were maintained, perfected, occasionally even calcified, in early or late modern times in the form of an all-embracing parliamentary culture.

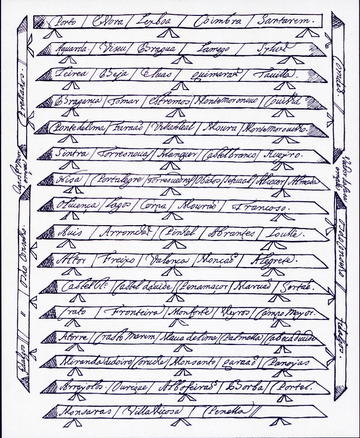

The seating of the towns at the Portuguese cortes of Évora-Viana in 1481. Hierarchical ranks should be read from top center (Lisbon), alternately decreasing toward left and right, and from front to rear: Á. Lopes de Chaves, Livro de apontamentos, 1438-1489, ms. 443, Pombaline Collection, National Library of Portugal. From: A. Mestrinho Salgado and A. José Salgado’s edition of this manuscript, Lisbon, 1984, p. 117-118.

From a literary and artistic point of view, such innovative practices did not go unnoticed. A participant in the October 1356 solemn meeting of the three estates of the kingdom of France, in dire circumstances, wrote a detailed narrative of the whereabouts of the assembly, in the form of a dedicated “Journal”, testifying not only to the political importance of the event but also to the perceived novelty of the ceremony. The anonymous author of the English appropriately named “Anonimalle Chronicle” similarly committed to writing the paramount importance and highly ritualized developments of the Good Parliament held by the aging king Edward III in 1376. Such narratives became common practice in the course of the following century. Still a long way from more official rolls or journals, developed in early modern times, by acknowledging the procedural efficiency of these early parliamentary performances, they contributed not so much to the institutionalization of such gatherings as to the general acceptability of new ways of politically doing things. This in turn resonated in a new way in the emerging public sphere of the period. Political pamphleteering, and moral and satirical literature seized on the novelty of such highly visible ceremonies, either to celebrate imagined idealized communities, as the Catalan “Corts of Jerusalem” presided by Christ himself, or to satirize, even ridicule, members of the Commons who “slumbered and slept” according to the anonymous late fourteenth-century Richard the Redeless, or “cried kek kek and kokkow” as Chaucer put it in his famous fable Parliament of Fowls. At this point in time, an emerging form of parliamentary culture, ere now embryonic, was making its way into the general public sphere of Latin Christian Europe.

Jan Matejko, Polish 19th-century exponent of history painting, rendered in very imaginative detail a modern perception of an otherwise very poorly documented medieval assembly, the great Sejm held at Łęczyca in 1182. National Museum, Royal Castle, Warsaw. Wikimedia Commons.

To sum up, I have suggested that late medieval Europe experienced a “parliamentary moment”, closely related to the rise of the so-called Modern State, prior to the establishment and strengthening of “new” and more autocratic, often deemed “absolute”, monarchies in later times. Far from even pretending to be democratic, these polities paved the road to innovative practices, such as building consensus, thinking the political relation as a contract between princes and subjects and, in the longer run, giving birth to imagined communities of later and much more recent times. Not unsurprisingly, nineteenth- and twentieth-century architecture and the decor of parliament buildings often pictured half-legendary landmarks, such as Jan Matejko’s imaginative rendering of the celebrated Polish Sejm of 1182 or Charles Giron’s beautiful 1901 landscape painting of the meadow of Rütli, mythical birthplace of the Swiss confederation, right in the Chamber of Assembly of the Federal Palace of Switzerland. Although parliaments, in their modern embodiment, were at a nascent stage of development, late medieval ceremonial practices, legal devices and social representations gave rise to a parliamentary culture that flourished from then on and whose memories are a continuing feature of modern political life.

Michel Hébert, Emeritus Professor, Université du Québec à Montréal.