Learning to Worry about the Enlightenment in Korea, 1917

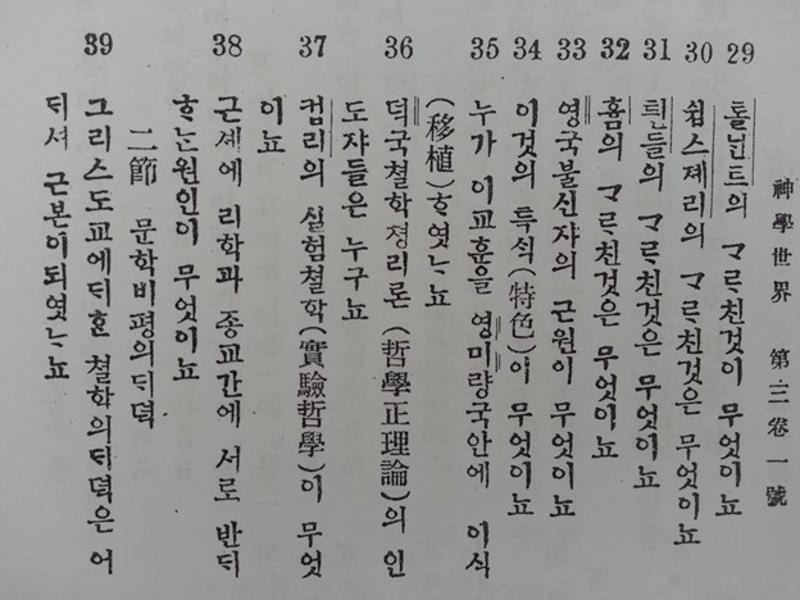

In 1918 (Taisho 7), students at the Methodist Union Seminary in colonial Korea were being quizzed about John Toland, Matthew Tindal, and the third Earl of Shaftesbury as part of their apologetics (辯證論) class. ‘What were the characteristics of English atheism?’ reads Question 34. Question 36 asks for the notable figures of German rationalism. Another was, ‘What ancient philosophical doctrines did the English deists use to attack Christianity?’ And finally, ‘What did Spinoza write in 1670?’ (the answer: Tractatus Theologico-Politicus).

신학세계 / 神學世界 (Theological World), 1918.

Roughly four decades after arriving on the Korean shore in the 1880s, Anglo-American Protestant missionaries were heavily represented in Korean higher education in the 1910s. Setting aside the obvious ideological and confessional slant, these questions do not square well with the conventional scholarship regarding American-borne Protestantism in Korea as a merry band of anti-intellectual fundamentalists preoccupied with a flock of dishonest converts, or the ‘rice Christians’. Conventional scholarship surveying the first two decades of twentieth-century Korean thought confidently reports this period as a frosty hinterland. The terminal decline of neo-Confucianism, the state orthodoxy since 1392, was made final when Japan colonised Korea in 1910, ushering in the brute forces of secular modernity.

If the Methodist Union Seminary’s sincere denunciations of British freethinkers such as Tindal and Toland—who variously denied the Trinity, the veracity of the Scripture, and the divinity of Jesus—strike us as deeply anachronistic, they also indicate an unexpected conceptual priority, a clarity of purpose: the Christian imperative to combat atheisms.

Portrait of John Toland.

In this blog, I sketch the introduction of the notion of ‘atheism’ in Korea in the 1910s and highlight two reasons as to why the missionaries drew attention to the impiety of the early Enlightenment freethinkers: the vulgarisation of Jewish history and Christian anthropology. In so doing I sketch a brief biography of Charles Scott Deming (1876-1938). An American Southern Methodist revivalist missionary, he was a professor of theology in Korea from 1911 to 1927. Graduating from Drew Theological Seminary in 1902, his main responsibility in Korea was teaching Systematic Theology, Practical Theology, and Biblical Church History. His remit eventually encompassed Historical Theology, Ecclesiastical History (mainly denominational), and a liberal arts course stretching from ancient Egypt to Abraham Lincoln. His presence in Korea goes largely unremarked, except as one of the foreign eyewitnesses to the so-called Great Awakening of Pyongyang in 1907, part of the global evangelical chain reaction that started in Wales in 1904.

Teacher and pupils Seodang, Kim Hong-do, c.1780.

Deming faithfully reproduced in Korea what he had learned at Drew. He drew from the Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature (12v; 1866-1881), which was intended to serve circuit riders and ministers alike. His lessons are peppered with references to not only the Enlightenment freethinkers but the pitfalls of ancient Epicureanism, the findings on the Chaldean rituals, and the textual history of the Septuagint. He also innovated by reinforcing several components, including Ecclesiastical and Biblical Histories.

Tiger under the pine tree, Kim Hong-do, late 18th century.

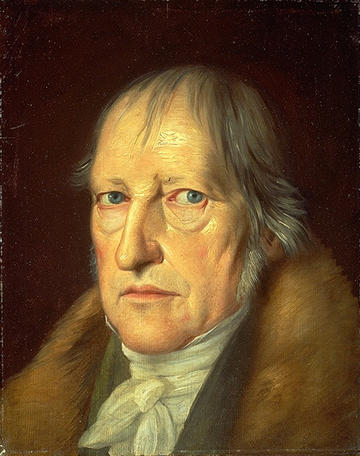

Amongst the missionaries Deming was unusual in showing little interest in the modern taxonomy of atheisms. He was at pains to draw attention to the varieties of atheism and materialism across human history, all the way from the ‘Greco-Roman peripatetic philosophers’ to the ancient Jews, and from Confucius to the Enlightenment. For instance, he writes that the philosophical atheism that jogged the pen (or brush) of Confucius was the very same that motivated the Jewish priests in ancient Alexandria and Hegel in nineteenth-century Germany to savage the Scripture. Indeed, he suspected the discipline of comparative religious studies itself, founded by German scholars, of atheist tendencies. But the flames of the Russian Revolution (1917) utterly escape him. The evils of Darwinian evolutionary theory are noted, but narrowly construed as a sub-specie of materialist atheism.

1831 portrait of Hegel by Jakob Schlesinger.

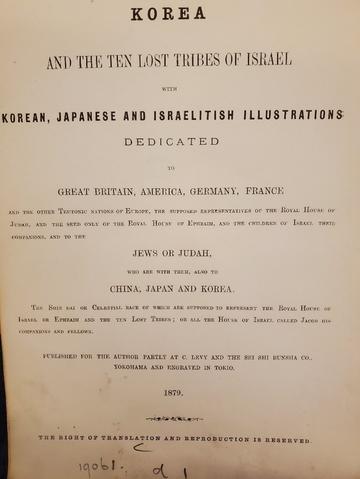

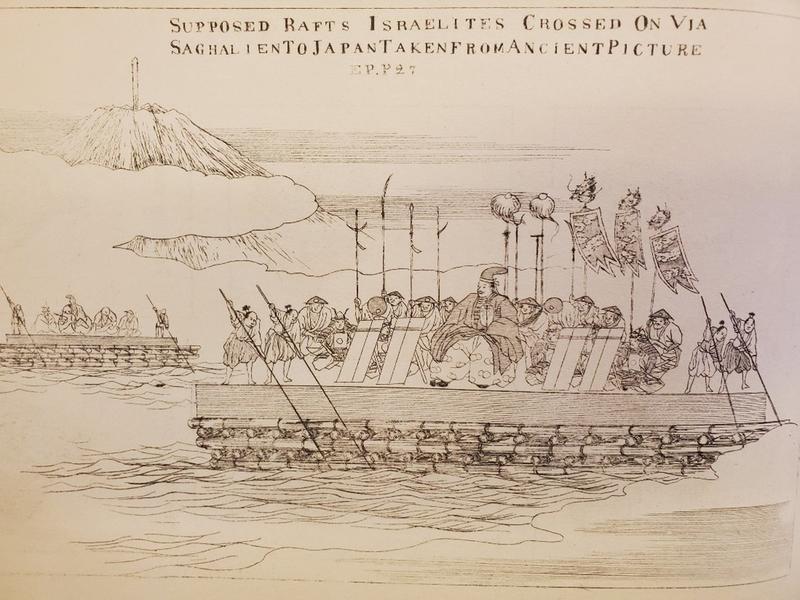

Deming's historical concerns were in part a response to the crass and opportunist appropriation of biblical scholarship by other Western missionaries. Contributing to the growth of atheistic unbelief in Korea was the blatant exploitation of the conceptual difficulties in reconciling Christian and pagan historiography. There were popular, if incredibly disingenuous, attempts by the western sojourners in Northeast Asia to assimilate Korean and Japanese history with that of the Bible. Nicholas McLeod's Korea and the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel with Koreans, Japanese and Israeli with Illustrations (1879)—a sequel to the popular Illustrations to the Epitome of the Ancient History of Japan (1877)—was an instance of racial plagiarism in which the Koreans and Japanese were, somewhat unoriginally, portrayed as the Lost Tribes of Israel. A fevered work of Victorian race fiction (the book was funded by the Palestinian Exploration Fund and printed in Edinburgh), the missionaries had reasons to be anxious about such amateurish and maladroit narratives.

Korea and the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel with Korean, Japanese and Israeli Illustrations (1879)

The yawning disjuncture between Christian Sacred History and the Sinocentric universal chronology to which Korean antiquity was annexed made it easy prey. Paring down the most egregious of these vulgar popularising tendencies, Deming’s Biblical Exegesis sought to place as much temporal and spatial distance between Korea and Israel as possible. He made it explicit that whilst similarities exist with respect to idol worship and ancestral venerations between the two nations, the coincidence was owing to the prevalence of primitive religious beliefs natural to those only reared on natural philosophy. This allowed missionary educators to pivot to the more pressing issue: the conception of the soul.

An Illustration to the Epitome of the Ancient History of Japan (1877).

By 1917, the Korean Protestants waxed eloquent on the centuries-old notion of the soul that issued from Neo-Confucianism. From the missionary perspective the philosophical skirmishes could be won decisively by undermining the Neo-Confucian notion of mortalism, the idea that the soul is in some way physical and subject to natural annihilation. In its place, the Christian doctrine of immortality of the soul had to be installed. Structurally, Protestant apologetics leaned into refuting this 'pagan mind-set' supposedly crippled by pure speculative tendencies. Deming believed that the accurate presentation of Christian anthropology and Sacred History would dispel the naturalistic atheism of Confucian philosophy.

Little, however, did the missionaries know that the Korean Confucians themselves had long locked horns with this very dilemma since the sixteenth century, and increasingly resolved to bypass the impasse by way of the metaphysical foundation of human mind. American missionaries ascribed Korean reticence to an inertia of mental habit similar to dogmatic medieval Aristotelians. Reiterating the immortality of the soul against the corruption of the Confucian ‘priestcraft’ that fed materialistic atheism, the missionaries failed to notice that the Korean converts were in fact far more fascinated by the physics of bodily resurrection than the immateriality of the soul.

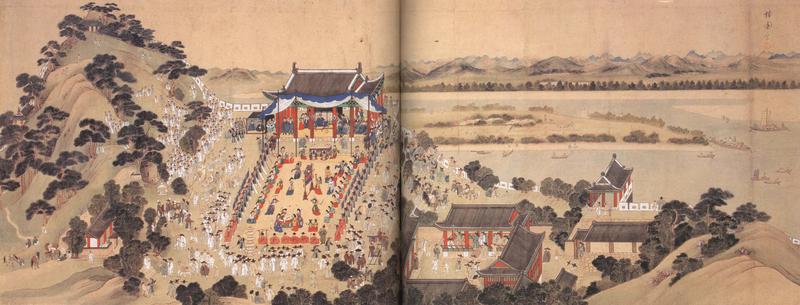

Feast for the Pyongyang Governor (1, Dinner), Kim Hong-do, late 18th century.

What relevance does this story of atheism hold for intellectual historians interested in the global transmission of ideas? It suggests a trajectory of early Enlightenment religious ideas that enjoyed a different pace of transmission. The role of institutions in regulating the tempo of transmission, set by its inner cadence of movements and cycles, is also of interest. Lastly, the conceptual reconciliation of competing sacred and mythic histories has further implications. But I want to draw attention to something rarely considered: the shifting meaning of atheism at this time in Korea.

Having been reduced to a colonial province of the ‘polytheistic empire’, with its full-blooded emperor cult, Korean Protestants saw their fate as being no different than the Christians in the third century. Even as American missionaries considered coming to an accommodation with what they regarded as the necessary evil of the imperial Shinto, Korean Protestants saw no defensible sanctuary of conscience in imperial policy. The history separating their lived experience from those recorded by Eusebius of Caesarea (260-339) had become daily obscure by 1919, the year of massive civil protests and the bloody military retaliation. For the fledgling Korean flock, to study Patristics was to experience their apocalyptic vision. Stalking the disavowal of the Christian God was hardly freethinking atheism and ungodly materialism. Zealous devotees of empire accused private unbelief of civic impiety, doubts with defeatism and fatalism. Atheism, the refusal to honour and venerate the living god emperor of Japan, thus invited persecution. Deming’s rebuke of Toland and Tindal would have been all too incongruous for his students.

Young-Chan (Justin) Choi is an affiliated member of the Oriental Institute, Oxford.