Milton, Literary Studies, and Intellectual History

John Milton had an unusually interdisciplinary career: he is almost as well known today for his writings on liberty, nationhood, religious tolerance, and freedom of speech as for his major epic poetry. As a result, Milton Studies has long been one of the most interdisciplinary areas of literary criticism, to the extent that it has acted as a barometer for the field’s receptivity to historical approaches. How has intellectual history influenced readings of Milton thus far, and what new directions might the study of Milton indicate for the future?

For literary critics, the most influential trends in intellectual history are those that allow us to revisit longstanding tensions in early modern literature in new ways. For example, one well-known problem in Milton’s work is that he is deeply committed to popular sovereignty, yet his conclusions often seem elitist, at least from our perspective. Critics once argued that Milton abandoned politics in later life, but historians of republicanism transformed this approach. “Republicanism” is too complicated to properly define here, but in Milton Studies it usually describes his view of liberty as protection from arbitrary rule, his emphasis on civic virtue as the precondition for liberty, and his tendency to treat virtuous citizens as the bearers of popular sovereignty. This approach proved highly influential for Miltonists because it allowed them to argue that Milton did remain committed to liberty, tolerance, and popular sovereignty, even in his later writings, but he was unwilling to extend these privileges to the popular majority because they, in his eyes, were not as virtuous as the better part of the nation.

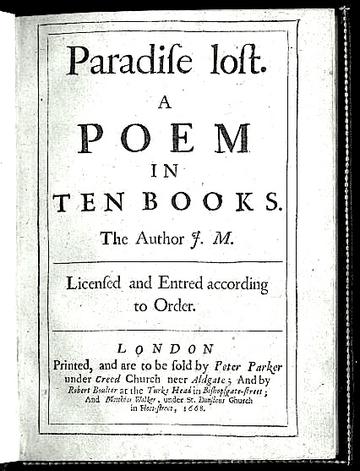

John Milton

The problems that spurred this interdisciplinary interest in the past continue to inspire novel approaches today. One of the most incisive interventions in the study of Milton’s idea of liberty is Mary Nyquist’s Arbitrary Rule, which reminds us that those who fulminated against the metaphorical “slavery” of arbitrary rule often justified, on the same grounds, chattel slavery for other nations. Nyquist’s approach reveals that intellectual history and literary studies are each made stronger by their mutual encounter: historical approaches help us connect political rhetoric to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, while literary analysis reveals the ideological claims underpinning political debate as much as early modern epic. Other critics have responded to the growing interest in religion in early modern studies by exploring how republicanism intersects with Milton’s theology. For example, Feisal Mohamed has argued in Sovereignty (2020) that Milton—like one of his models, Henry Vane—is best described as a “godly” republican because he bestows sovereignty on a minority of elect saints rather than on the people as a whole. This argument joins a growing interest in seemingly inclusive categories, such as “people,” “community,” and “nation,” which upon closer analysis can imply a few elite individuals speaking on behalf of the whole.

While the authoritarian themes of Milton’s work have spurred significant interest, the revolutionary side of Milton continues to inspire stimulating, interdisciplinary research. James Simpson’s Permanent Revolution, for example, is a sweeping study of religious liberty as an inspiration and unruly sibling to liberalism, and one of its key starting points is Milton’s revolutionary understanding of liberty. By the same token, the title of Nicholas McDowell’s new biography, Poet of Revolution: The Making of John Milton, captures how poetic “making” is interwoven with what we normally mean by “revolution.” William Poole’s magisterial Milton and the Making of Paradise Lost similarly draws upon a vast breadth of intellectual history to explain how Milton’s “making”—both his self-making and the making of his main epic—amounted to what we might call an aesthetic revolution in English poetry. It is not yet clear what the future of “revolution” as a historical or literary concept will be, but Milton is likely to invite further explorations in this direction.

These examples illustrate how future approaches to literature and intellectual history might explore the role of language and style in poetically “making” key concepts such as “people,” “community,” “sovereignty,” and revolution. Because early modern writers often imagine their political communities as ideals and aspirational visions, the political stakes of early modern texts are often implicit in the kind of details we now associate with literary criticism—such as a text’s metaphors, similes, diction, rhetorical figures—rather than explicitly stated as argument. What does it mean, for example, for Milton’s Areopagitica to describe the English in their moment of revolutionary fervor as “a noble and puissant nation rousing herself like a strong man after sleep”? How does a “Nation… herself” become “a strong man,” and how does Milton’s self-representation underpin this transformation of a nation into a man, and vice versa?

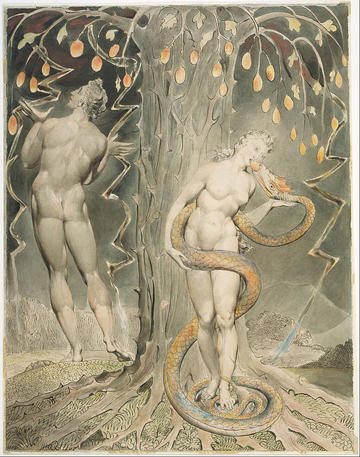

William Blake, 'The temptation and fall of Eve illustration to Milton's paradise lost', Google art project.

I explore similar questions in my own work by asking how poetry repurposes theological doctrines to imagine idealized versions of political community. Milton is a crucial figure in this story because he repurposes key words, such as grace and the Trinity, to present himself as the paradigmatic example of what the political nation could become if it were educated in the right way. In my work, as in the other studies I have mentioned, Milton is a window into a larger history of how metaphor and style bridged politics, religion, and literature in a time of crisis.

Similar questions could be asked of virtually any early modern writer, and the most fruitful approaches are likely to remain those that weave literary and historical methods. Different institutions have developed unique ways to promote this kind of collaboration, and their efforts will be more fruitful if they share their most successful strategies with one another. Oxford is an excellent place for interdisciplinary efforts, for example, because its traditions and college structure stimulate conversations between faculties and collaborative research. This approach to interdisciplinarity is not only good scholarly practice, but also the attitude that is demanded by early modern texts themselves at their most provocative and ambitious. Milton will remain part of this conversation not simply because he was ambidextrous in his writing, but also because in his work we confront our own critical desire to step between the boundaries that divide literature from history, political thought, and theology.

Deni Kasa is a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow at Wolfson College, Oxford.

More from the Blog

Follow us on Twitter @OxfordCIH