Parliamentary Culture, 1500-1700: The State of Research

Research into representative institutions has a long history. Starting in the nineteenth century, newly established national states have supported their legitimacy by promoting the publication of extensive source material concerning the prehistory of their parliaments. That is still happening, for example in commission from the regional parliaments of Catalonia and Sardinia, and for the kingdom of Aragon. Portugal, too, celebrates the parliamentary democracy it acquired in 1974 with a richly sourced publication about the medieval Cortes. Since September 2021 the resolutions of the Dutch States General in the 18th century are accessible online; this resource should be extended to the 16th and 17th centuries by 2023.

Numerous studies that described institutions in a regional or national context followed. The multiplicity of the institutions’ names is linked to regional differences in their composition and activities. This makes the comparison among countries rather difficult. Researchers therefore exhibit a tendency to interpret the institution that they are describing as a unique phenomenon and in any case to treat it as a special occurrence. On the other hand, there is a tendency in the historiography to elevate one specific concept to a general model, as often happened with ‘three Estates’, while reality exhibits a lot of diversity.

Mural of the Diputación del General in the Palau de la Generalitat, Valencia. Photo by Wim Blockmans.

In his impressive comparison of the Estates in the countries ruled by the Habsburg monarchy, Petr Mat’a points to the inhibitions (he refers to ‘blinders’) imposed by historical or contemporary regional or national boundaries (Habilitation thesis Vienna, 2020). Moreover, national traditions exhibit very different dividing lines: in Bohemia and Moravia the Battle of White Mountain in 1620 is held to be an absolute break with the past, as a result of which continuity is lost from sight. Furthermore, Mat’a rightly criticizes the explicitly dualistic approach that particularly marks German-language research, whereby rulers and estates were supposed to be engaged in a zero-sum game in which each aimed solely at the other’s downfall. The centuries-long functioning of monarchies with representative institutions points at variable forms of interpenetration. The intermediary power of representative institutions could be functional in both directions without necessarily annihilating the other side, as the King of Denmark could stop summoning the Rigsdag after 1660.

The vision from the point of view of the monarchy characterizes the most recent overview published by Michael Graves in an educational series in 2001. He deals principally with the formal aspects of representative assemblies at the level of a large number of European states, from the earliest reports in the twelfth century to the end of the seventeenth. It is unclear why the eighteenth century is excluded, but he does allow the longue durée to appear to full advantage and he processes a lot of information. The brief handbook by Alec R. Myers, dealing with all of Europe in the ancien régime, offers the best concise overview of the subject but is by now half a century old. Back in 1975, he observed that:

in the last forty years much research has been done on particular parliaments and on special aspects of their organization and role; but this is the first comprehensive study of their rise and progress as a phenomenon of Western Europe.

One year later, his German colleague Gerhard Oestreich called for comparative research on this matter, applying ‘fundamental categories’ as analytical tools:

the essential problem is the fact that each national evolution developed in its own way, differently from the others. Consequently, most researchers until now considered it nearly impossible to attain a comprehensive vision of the European development. […]

A new analysis [is needed] of the fundamental categories […] forming the precondition for the comparative work which remains the aim of our research.

Since then, many sources and partial studies have been published, mostly focussed on normative frameworks and confined by current state boundaries, but a comparative study that tries to explain the evolution of the actual influence of these institutions is still lacking. The book Parlementer by Michel Hébert (2014) supplies this magisterially for western Europe before 1500, but central and northern Europe remain outside its consideration. These regions are dealt with in a much shorter overview that he published in 2018.

It is my conviction, however, that the chronological division between the ‘Middle Ages’ and ‘(early) Modern period’ neglects the continuity of representative institutions to the end of the ancien régime. They perpetuated the institutions that had been formed in the Middle Ages, but in the course of time they also developed new functions and working methods. Some of them, notably in the Swiss Confederation, the United Provinces, Great Britain, and partly also in Sweden, even played a decisive role during the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, precisely because of their unbroken continuity from the Middle Ages onwards. The Swiss Tagsatzung, the Dutch States General and the Provincial States exercised sovereign power, from the late 14th century and the 1570s respectively; after 1689 the English King and Parliament were joint bearers of sovereignty. Aside from these cases, in the 16th and 17th centuries, representative institutions generally lost power, were side-lined or reduced to a role of symbolic self-assertion.

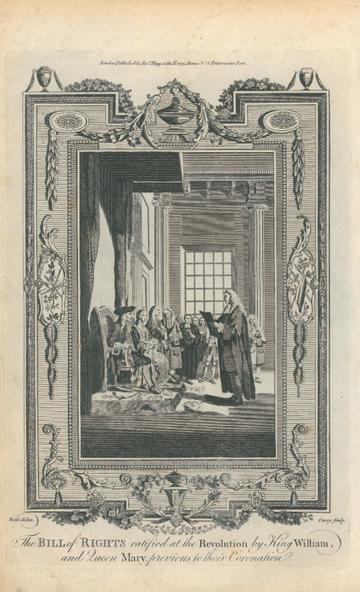

Eighteenth-century engraving showing the Bill of Rights (1689) being presented to King William III and Queen Mary II of England, created by a certain "Carey", c. 1797 (Public Domain).

The Challenge

The most intriguing question to be asked about the period from roughly 1500 to 1700, is why representative institutions flourished in four countries while elsewhere they went into decline, un largo sueño as it was called in Castile. Large historical processes as these cannot be explained by any form of reductionist argument, limiting the relevant factors to either materialistic or idealistic categories, or to political events and processes. Following Gerhard Oestreich’s call for an analytical framework for comparative research, I propose an outline of such an approach. Let me list here my ‘fundamental categories’ in a schematical way.

First, some structural features need to be considered; within their context, political interaction, contingencies, external interventions, and processual changes lead to a variety of outcomes.

Among the structures, the conditions of the natural geography are fundamental, offering opportunities in the form of natural resources, facilities of transport and communication, a maritime or land-locked location, space for expansion. On the other hand, challenges may include natural obstacles, such as marshlands, forests and low soil productivity, aggressive neighbours. Landscapes favour the formation of communities, sharing language, beliefs, customs, and law. Depending on the population density and social interactions, political communities become stabilized, which may imply direct participation in decision-making on the local level in tings and Gemeindeversammlungen. Regional association from the bottom up may lead to Landschaften, waterboards, leagues, Hermandades. Top-down organization by the military estate led to lordships, hundreds, counties/shires, principalities, monarchies. The tension between community and lordship is a key issue in European history, up to the present day. Once a political structure has been established for a long period of time, it tends to be perpetuated, as the positions of power become entrenched in traditions, privileges, law, and institutions.

Second, human interactions change the initial settings from within or from outside, in various ways and rhythms. Monarchs’ successes and excesses, dynastic (dis-)continuity, imperialism, social and economic effects of warfare, revolts: all such contingencies may reshuffle the power balance. Preponderant resources and cohesion of the established elite(s) strengthen central power, weaker concentrations challenge it. Parliamentary systems based on representation by mandate from the political communities and accountability to them, typically flourish in situations where various types of resources are controlled by diverse collective actors.

Long-term processes trigger changes in the power balances between social classes and within institutional settings. Economic and demographic trends lead to redistributions and the rise or decline of particular categories of people. Institutions may slow down the effects or accommodate in order to maintain the attained positions as much as possible. The rise of the fiscal-military state was one of the major developments in the early modern period. Its effectivity depended on the available resources and the organizational capacity of the elites. Existing structures may become inverted through collective and individual egoism, shifting their goals from representation towards patronage. Within representative institutions, oligarchizing, institutional inertia, rent-seeking, incorporation of local elites into the state apparatus, tended to gradually corrupt or dissolve the system.

Satirical painting by William Hogarth ('Chairing the Member') about the election of a member of parliament in Oxfordshire, 1754. Part of the Humours of an Election series, 1754-55. Sir John Soane's Museum, London (Public Domain).

Parliamentary Culture

Representative institutions could only emerge and continue functioning in polities in which no single category (e.g. the monarchy, a metropolis) or estate was predominant. The key prerequisite for the functioning of such a political system was the preparedness to negotiate, with minds open to other people’s interests, and the capacity to compromise. Such attitudes are more likely to emerge in communities interacting with others, within cities, regions, and typically in trading relations.

A second essential feature of representative systems is the concept of a common weal, transcending the individual, class or local interests. This notion was repeatedly mentioned in the context of a dynastic crisis in Flanders in 1128, and became widely circulating in the European learned circles since Thomas Aquinas formulated it around 1250. Monarchs as well as cities used the argument for their own purposes, in the awareness that they would have to meet other interests than their own.

A third general aspect is that representation brought people together from all parts of a polity, linking the centre with the periphery, which should be beneficial for both sides. That helped to spread formal as well as informal information. The mere fact of having to spend weeks or months together, dealing with others and listening to other arguments than one’s own, socializing even, was highly instrumental in enhancing the understanding of the complexity of political decision-making.

A fourth characteristic of parliamentary culture in the ancien régime is that it was fundamentally based on social hierarchy and inequality, on individual and collective privileges. The structure in Houses, Chambers, and Estates, counties, cities and boroughs, and the permanent attention paid to precedence were just expressions of the deeper understanding of the limits of each participant’s agency.

Finally, the 16th and 17th centuries widely demonstrated the limits of dissent tolerated in religious matters.

Wim Blockmans, Emeritus Professor, Leiden University.