Parliamentary Culture and Library History in Britain

How did provincial men and women in the early modern period (roughly from 1600 until 1800) experience parliamentary culture? The history of the ‘public sphere’ will direct us towards pamphlet literature and newspapers in coffee houses and taverns. A different eighteenth-century institution which has received less attention – but one that became increasingly important for allowing the middling sort to educate themselves about politics, debates and political institution – was the subscription library.

The Lending Library, by Isaac Cruikshank, between 1800 and 1811.

Inspired on the one hand by rising literacy rates and the increasing cultural capital of reading amongst the middling sort, and on the other by the continuing high price of new books, the subscription library was essentially a book club which allowed members to pool their resources to acquire a larger permanent collection of books than any of them could afford individually. As we shall see, these collections often included parliamentary records and history.

Certain kinds of library were already reasonably familiar in British towns of the mid eighteenth century. The earliest ‘public’ libraries were founded in Norwich in 1608, Ipswich in 1612 and in Bristol in 1613, the latter in a building donated to the city for the purpose by Bristol merchant Robert Redwood and supplemented subsequently by books bequeathed by Bristol-born Tobias Mathew, Archbishop of York. Founded generally by philanthropists, these early “public libraries” aimed to preserve knowledge and make it publicly available to scholars and clergymen – but with little expectation that ordinary people would have any desire or need to use their books. Elsewhere, books could be read in situ – and occasionally borrowed – from several Cathedral libraries, while commercial book lending (initially from coffee shops and taverns, and increasingly from formal ‘circulating libraries’ run by booksellers on a profit) was also becoming a familiar – and not uncontroversial – part of the urban book scene in the early decades of the eighteenth century. The subscription library model was fundamentally different to existing models.

Whereas the choice of books – and the means of accessing them – was generally controlled at other types of library by a single individual (by the philanthropist responsible for endowing a public library, for example, or the bookseller operated a commercial circulating library for profit), these decisions at the subscription library, crucially, lay in the hands of subscribers, who determined the rules of the institution, its membership fees, opening hours and acquisitions policies on a collective basis.

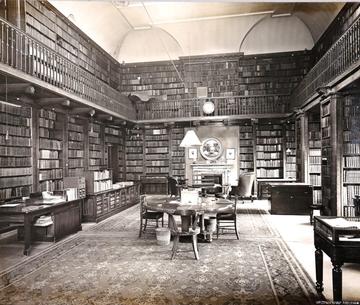

The library room at the Athenaeum in Liverpool.

The subscription library model was first pioneered in Philadelphia in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin’s famous ‘Junto’ debating club as a pragmatic solution to the practical difficulties of accessing new books in a colonial city far from the centre of British book publishing in London. This model proved a great success on the colonial seaboard, before spreading first to the Scottish Borders, and then to the rapidly growing industrial towns of northern England. The first formal subscription library in Liverpool was founded in 1758, followed by similar libraries founded in Warrington (1760), Carlisle, Halifax and Leeds (all 1768), Macclesfield (1770), Sheffield (1771), and Bristol (1772/3). Some were exceptionally exclusive social institutions, charging prohibitively high subscription fees and blackballing undesirable prospective members, but many more encouraged members from quite far down the social scale – so that we can occasionally access through their records the reading lives of tailors, millers, students, artisans, and bakers, as well as wealthier members of the landholding, mercantile, or professional elites. And while the merchants and manufacturers who tended to lead libraries were sometimes fabulously wealthy, they often lacked formal education, and may indeed have been the first generation of readers of books in their families. Most subscription libraries also had a smaller number of female members.

The connection between subscription libraries and parliamentary culture extends to both books and people. In the first place, many of Britain’s and Ireland’s subscription libraries were actively supported by local members of parliament, who were frequently library members, as at the Norwich Public Library, Stamford, the Huntingdon Book Club, and the Liverpool Athenaeum in England, the subscription libraries in Wigtown and Kirkcudbright in Scotland, and at Cork and Dublin in Ireland.

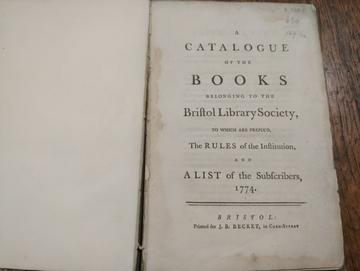

The Bristol Library Society Catalogue from 1774.

A particularly well-documented example is the Bristol Library Society. On 2 February 1773, only two months after the first meeting of the library was held, the library’s chairman presented a letter from Robert Nugent, known in Bristol as Lord Clare after the title of his Irish peerage, who had represented the city in the House of Commons since 1754. The letter expressed Clare’s intention of becoming a member of the library. At the same meeting, a letter was presented from Matthew Brickdale, Bristol’s second representative since 1768, – most English constituencies had two representatives at this time – who ‘desir[ed] to be informed, whether an annual subscription or for Life would be most acceptable.’ The committee instructed the chairperson ‘to inform him that the Committee return him thanks for the alternative, and that a Subscription for Life would be most eligible.’

In the event, both Clare and Brickdale became members for life of the library, a status that was obtainable for the price of fifteen guineas or more, fifteen times higher than the regular entrance fee at the time. Importantly, Brickdale also donated his own very respectable collection of books to the library, which was attached as an appendix to the first printed catalogue of the Library Society, published in 1774. In the early years of the library, Brickdale’s books comprised a high proportion of the library’s lending. Since Brickdale came from a political family who were prominent members of the Steadfast Society, representing the Bristol Tories, among his books were many of parliamentary and political interest, including a large collection of law books.

Edmund Burke, MP for Bristol in 1774-80.

Both Clare and Brickdale lost their seats at the general election held in the autumn of 1774. Their example to become members for life was followed by one of the city’s new representatives, Edmund Burke, though not by Burke’s fellow MP, Henry Cruger, who remained a regular member. This is probably due to the fact that Burke’s close supporters and local agents in Bristol were leading members of the library, especially Richard Champion and Joseph Harford. The library’s first printed catalogue includes four asterisked donations from Burke: a quarto edition of Burke’s Speech on American Taxation (1775), and the octavo editions of his Vindication of Natural Society (1756), Observations on a Late State of the Nation (1769), and Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents (1770).

In addition to these association copies, the Bristol Library Society – in common with other subscription libraries – held a comprehensive set of volumes on parliamentary history, including The Parliamentary or Constitutional History of England; from the Earliest Times to the Restoration of King Charles II. ... By Several Hands (24 vols., 1763), Debates of the House of Commons, from the Year 1667 to the Year 1694 (10 vols., 1769), The History and Proceedings of the House of Commons from the Restoration to the Present Time (12 vols., 1742), and sixteen volumes of The Statutes at Large, collected by Owen Ruffhead.

These parliamentary sources were not nearly as popular as travel literature, narrative history or sentimental novels, which we know thanks to the high number of surviving borrowing records at Bristol. However, their presence gave members of the middling sort an opportunity to familiarise themselves with parliamentary sources at a time when many of them were franchise holders in urban settings, including in Bristol with a diverse electorate of around 5,000 voters. These library records – which are currently being collated into a major open-access database by the AHRC-funded Libraries, Reading Communities and Cultural Formation in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic project at the University of Liverpool – helps us understand the role of reading in the political education of members of the middling sort beyond the metropolis in the pre-democratic age.

Max Skjönsberg, Postdoctoral Researcher, and Mark Towsey, Professor of Book History, University of Liverpool.

*Max Skjönsberg and Mark Towsey are currently editing the committee minutes of the Bristol Library Society in the eighteenth century for the Bristol Record Society. The volume is forthcoming in 2022, coinciding with the 250th anniversary of the library’s founding. The C18 Libraries Online database will be published open access in the summer of 2022, offering membership records, holdings and borrowing records from around eighty subscription libraries from North America and the British Isles between 1731 and 1801.