Parliamentary Government, Whig History, and the Cambridge School

At first glance, it would not appear that parliamentary history has traditionally been all that important to the history of political thought. Yet in the course of writing a book on the history and theory of parliamentary government, I became increasingly convinced that these two fields have been far more entangled than is generally realized. In the short space available to me here, I will try to spell out this intuition. I will do so by offering a new perspective on the so-called ‘Cambridge School’ in the history of political thought. I will suggest that much of the most famous work done by prominent Cambridge School scholars such as Quentin Skinner and J.G.A. Pocock might have appeared, to earlier generations, as a contribution to the history of parliamentary government.

'The House of Commons' by Thomas Rowlandson, in The Microcosm of London, published 1808-1810.

The Cambridge School is usually thought to be defined by a methodology, one which interprets texts and authors within their specific historical contexts. One of the first figures to gesture at such an approach was Herbert Butterfield in his 1931 book The Whig Interpretation of History. For Butterfield, ‘the Whig Interpretation of History’ signified two different things. In the first place, it signified a general attitude to the past. Historians who partake of this attitude fail to recognize the profound differences between their own historical context and the contexts they are studying. Instead of trying to understand the past on its own terms, such historians end up making absurd and oversimplified claims, for instance that Plato was a ‘totalitarian’ or that the English Civil War was a struggle to create modern liberal democracy. But the Whig Interpretation of History also signified, for Butterfield, a specific tradition of English historical inquiry. The seventeenth-century Whig historians wrote the history of England in terms of the loss of constitutional liberty and the decline away from the ancient constitution. For eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Whig historians, by contrast, the history of England was defined by the gradual progressive development of constitutional liberty over time. And, as Butterfield explained in his 1944 book The Englishman and his History, despite his profound opposition to the general mindset of Whig History, he could not but admire the work of England's actual Whig Historians, especially the nineteenth-century historian Thomas Babington Macaulay.

Image of Thomas Babington Macaulay from The Works of Lord Macaulay, published 1898.

Macaulay was an influential colonial administrator and Whig parliamentarian as well as a historian. He began publishing volumes of his most important work, The History of England from the Accession of James II, in 1848, though the endeavor as a whole remained unfinished when he died in 1859. This was a history of England that was indeed Whiggish in both of the senses that Butterfield identified. It begins in the seventeenth century when powerful absolutist states emerged across Europe and, in many places, extinguished the remnants of the mixed constitution. Macaulay contends that England was saved from this fate by the English Civil War and Revolution of 1688, which enabled Parliament rather than the Crown to reign supreme:

In the neighbouring kingdoms great military establishments were formed; no new safeguards for public liberty were devised; and the consequence was, that the old parliamentary institutions everywhere ceased to exist… The introduction of a new and mighty force had disturbed the old equilibrium, and had turned one limited monarchy after another into an absolute monarchy. What had happened elsewhere would assuredly have happened here, unless the balance had been redressed by a great transfer of power from the crown to the parliament. Our princes were about to have at their command means of coercion such as no Plantagenet or Tudor had ever possessed. They must inevitably have become despots, unless they had been, at the same time, placed under restraints to which no Plantagenet or Tudor had ever been subject.

For Macaulay, this ‘great transfer of power from the crown to parliament’ secured liberty without undermining the authority of government. In the eighteenth century, the Crown’s ministers were increasingly drawn from and accountable to the House of Commons. Through this mechanism, Macaulay argued, ‘the House of Commons can exercise a paramount influence over the executive government, without assuming functions such as can never be well discharged by a body so numerous and so variously composed.’ Yet the eighteenth century also revealed a profound new dilemma for parliamentary politics: corruption. As Macaulay explains, ‘the House of Commons was more powerful than ever as against the Crown, and yet was not more strictly responsible than formerly to the nation. The government had a new motive for buying the members; and the members had no new motive for refusing to sell themselves.’ It was only in Macaulay’s own lifetime, with the passage of the Reform Act which he did so much to bring about, that the danger posed by corruption to the independence of the House of Commons had receded. ’The House of Commons is now supreme in the state, but is accountable to the nation,’ Macaulay wrote. In this new context, ‘the best way in which a government can secure the support of a majority of the representative body is by gaining the confidence of the nation’.

I would now like to suggest the following: when we turn to several of the classic texts of the Cambridge School, we find a history which is surprisingly parallel to what I have recounted above. It is, of course, focused much more on ideas than Macaulay’s was. More strikingly, it has an alternate ending: it ends not with the triumph of aspirations to parliamentary rule but with the defeat of these aspirations.

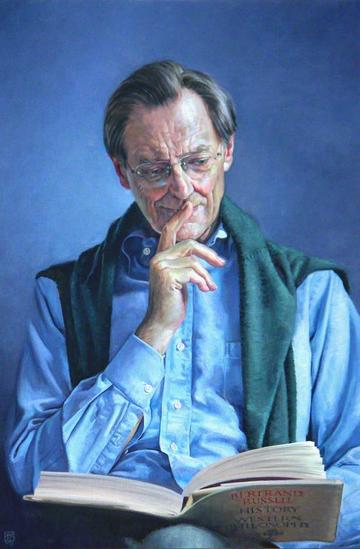

Professor Quentin R. D. Skinner by David Hugh Cobley, Christ's College, University of Cambridge (2012)

If we turn to Quentin Skinner, for example, at the very center of his historical work we find a struggle between Hobbes’s account of the modern state, and the argument developed by the parliamentarian side in the lead-up to the English Civil War, which specifically asserted that liberty required a ruling position for the House of Commons. It is not an exaggeration to say that this confrontation is of as profound historical significance for Skinner as it was for Macaulay: it is a struggle over the meaning of liberty, representation, the state, and the human sciences. We are still living with the consequences of it today. Yet according to Skinner, the ideals of the parliamentarians were ultimately defeated. It is Hobbes who has proven victorious. Indeed, it is worse even than that. Not only have the aspirations of the parliamentarian side been lost, there has been no synthesis of liberty and authority such as Macaulay perceived in the mechanism of parliamentary government. We are without either true liberty or the true benefits of a Hobbesian state, trapped between vague and dangerous aspirations to popular sovereignty on the one side, and the harsh reality of a powerful oligarchical governing apparatus on the other side.

If we turn to J.G.A. Pocock’s The Machiavellian Moment, we see a parallel story, extending into the eighteenth century. Whereas Macaulay celebrated the reform of the House of Commons and the decline of corruption, Pocock is clear that it was corruption—the managing of the House of Commons through patronage and interest—that heralded the future of modern politics. It was David Hume and Alexander Hamilton, with their forthright defenses of this practice, who correctly saw where things were headed. The ideal of an independent legislative assembly, in which virtuous landholders held sway, was overpowered in Britain. This ideal was briefly triumphant in the United States, only to be defeated there in turn, leading to ‘the greatest empire of patronage and influence the world has known.’

Unsurprisingly, given that he was a student of Butterfield, Pocock’s writings have more traces than Skinner’s of the kind of Whiggish narrative we saw with Macaulay. In several notable essays Pocock sketches the emergence in the nineteenth century of a reformed parliamentary monarchy in Britain, and he emphasizes that this was a unique modern political regime, quite distinct from the ‘republican empire’ of the United States. He also emphasizes that under this regime, Britain was able to eliminate the ‘most classical and familiar forms of patronage, influence, and corruption.’ Indeed, a reformed parliamentary monarchy may be the best answer we find anywhere in Pocock’s writings to the explosive conflicts of the Machiavellian Moment. Yet a reader can easily overlook this answer. For the much larger story Pocock has to tell is about these explosive conflicts and what they represent, namely the rise of a ‘a strong executive, with a base in public credit and a supply of political patronage’ and associated with both extreme oligarchic and populist political styles.

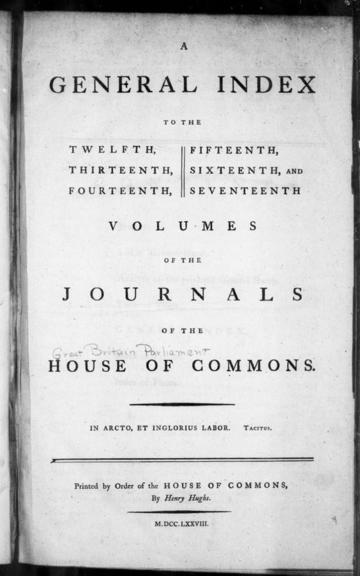

Title page of a General Index to the Volumes of the House of Commons, encompassing volumes twelve to seventeen, published 1778.

These are certainly not Whig Histories. But they are histories which are fundamentally about the legitimacy of parliament as an institution and the appropriate practices of parliamentary government. As a contextual matter, this is perhaps to be expected. They come out of an era when parliamentary history loomed very large in British history departments, indeed this was the era when Lewis Namier was a household name. But I don’t think this is the whole explanation. There has clearly been a resurgence of interest in these themes of late (as evinced by this very series) with young scholars exploring the history of political thought and parliamentary history in tandem. Nor are these studies limited to Anglophone contexts: they extend to the parliamentary traditions of many other nations, which have had equally rich debates about the nature and legitimacy of parliaments. To a significant extent, one cannot understand the intellectual history of such themes as liberty, corruption, sovereignty, representation, deliberation, executive power, or political parties without attending to the vicissitudes of parliamentary history. One of the key legacies of the Cambridge School was to link these fields together in a particularly powerful way, creating a tragic history of modern self-government.

William Selinger, Lecturer in the Department of History at University College London.