Parliaments as Meeting Places for Political Concepts

Conceptual, Digital and Parliamentary Turns in Intellectual History

Intellectual history has traditionally based its interpretations of the history of political thought on the works of great philosophers. Conceptual history shares with intellectual history an interest in how the meanings of key political concepts such as sovereignty and representation have evolved through history. Both genres of historical research focus on active uses of language and conceptual innovation aimed at affecting policy. Conceptual historians start with the assumption that we create, (re)define, evaluate, (ab)use and reject concepts to construct much of our social reality and that human interpretations of the world and consequently the exact meanings of political concepts are unavoidably contested. Historical analysis should hence focus on the use of concepts by past political actors themselves and not so much on concepts formulated by canonical thinkers or on the analytical concepts of present-day social sciences applied to the past.

Thanks to the mass digitization of parliamentary records in several European countries and comparative studies in the history of political discourse based on parliamentary debates, conceptual and intellectual history have recently experienced a parliamentary turn. We can approach parliamentary debates analytically as nexuses of past political discourses – as meeting places in which multi-sited and potentially transnational political discourses have intersected in the same time and space. Digitization has created opportunities for conceptual analysis based on the language of everyday politics: text-mining techniques can be applied to observe long-term trends in the use of political concepts, to compare different national contexts, and to locate political disputes that may have previously gone unnoticed. As well as analyzing general trends in conceptualisations quantitatively, it is possible to investigate qualitatively specific meanings assigned to concepts by individual politicians in particular political struggles.

‘Put it to the People’ march, London, 23 March 2019

Exploring Long-Term Changes in “political representation” with a Focus on Parliament

Tensions between the people and parliament have been central for the legitimacy of political decision-making at least since the eighteenth century. In the project Political Representation: Tensions between Parliament and the People from the Age of Revolutions to the 21st Century, we are making a conceptual, digital and parliamentary turn in writing the history of political representation. We have adopted an empirical, source-based and language-sensitive approach to political history, reconstructing competing conceptualisations of popular sovereignty and representation in their historical contexts. As we explore how members of parliament have understood representation and participated in its redefinition, we may qualify the way in which extra-parliamentary media and philosophical debates have been regarded as decisive for changes in political representation. At the same time, the availability of digitized newspapers and theoretical writings allows us to consider them as major contexts for parliamentary debates on political representation.

Towards Transnational Comparisons

In our interdisciplinary project, historians of political discourse, political scientists and digital humanities specialists cooperate to study parliamentary debates as nexuses of political discourses moving in time and space. We are interested in the history of popular sovereignty, political representation and parliamentary legitimacy in ten Northwestern European states – considered nationally, comparatively and transnationally. We challenge methodological nationalism by analyzing parliamentary debates from several countries instead of writing parallel histories of national exceptionality. It is time to move towards writing entangled parliamentary histories.

An obvious challenge concerns bridging close reading in national contexts with computer-assisted distant reading. As we make use of existing digital humanities methods rather than develop new ones, we have started to construct a comparative interface in cooperation with the Utrecht University Digital Humanities Lab who have developed I-Analyzer, a web based text and data mining application. We expect visualizations of extensive digital datasets to help us to get an overview of the big data, detect patterns and anomalies, formulate new research questions, and select cases for qualitative, contextual content analysis.

While building the interface, we recognize challenges in converting, cleaning and editing the data, especially with regard to the eighteenth and even much of the nineteenth century. We cannot rely on perfect interoperability between the different national datasets; debates in national parliaments need to be analyzed side by side rather than intermixed. The comparative database will nevertheless provide us with input for more conventional historical analysis. Contextualizing close reading of micro-level cases – for which we can use national interfaces such as Historic Hansard, Hansard Corpus and Hansard at Huddersfield (HaH) – will focus on political struggles surrounding political representation. Particular parliamentary debates and speech acts in them illustrate how rival political actors have exploited discourses on popular sovereignty and representation in political action.

Visualizations Lead to Hypotheses

We are thus interested in the dynamic relationship between intra- and extra-parliamentary political discourses in national contexts as well as in possible cross-national transfers. At the level of national parliaments, our research questions concern timing of debates, tensions over parliamentary representation and the representatives’ own conception of their parliamentary role.

As for timing, visualizations of relative word frequencies (ngrams) help us to see where and when political representation has been debated and how some typical representative claims have changed through time. Collocations, ngrams and close reading reveal tensions over representation, i.e. debates on who or what has been represented. As we wish to learn how these tensions have been manifested discursively and conceptually, it remains to be seen to what extent word embeddings, cluster analysis or word associations, for instance, will be helpful as opposed to traditional contextual content analyses.

To understand the relationship of discursive changes to structural change, we need to build on previous research. In order to estimate why certain discourses succeeded or failed to (re)construct parliamentary legitimacy, we need to discuss theoretical literature. Also in order to locate relevant debates for the representatives’ own conception of their parliamentary role, we need to complement distant reading with cases covered in research literature and with searches in digitized newspapers. The reconstruction of these conceptions calls for attention to how parliamentarians have dealt with competing claims of sovereignty from outside parliament, to how perceptions of extra-parliamentary interference have changed over time, and to what kind of representative claims representatives have used to legitimize their conduct.

Waves of Representation in the British House of Commons

As we have only just started, I cannot present any conclusions yet. Let us speculate a little on the basis of data from the House of Commons, however. HaH’s relative word frequency tool gives rise to several hypotheses on the history of political representation that need to be tested with contextualizing close reading and comparisons to other national parliaments.

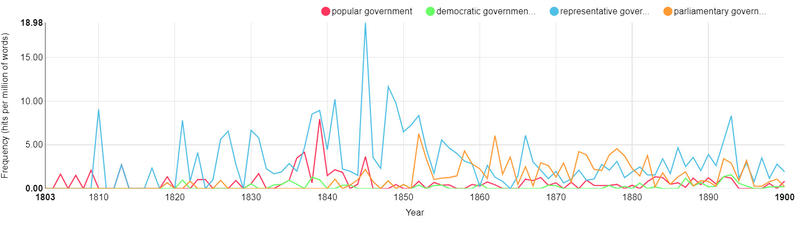

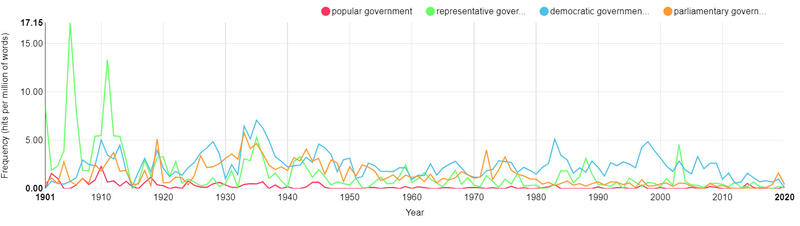

One observation on the bigrams provided by HaH is evident: In attributes qualifying the (British) government there have been major transitions from the essentially eighteenth-century ‘mixed government’ to the nineteenth-century ‘representative’ and ‘popular government’ and increasingly towards ‘parliamentary’ and finally to ‘democratic government’. More recently all of these would seem to have been placed with other terms (Figures 1 and 2). These transitions are confirmed by parallel shifts in the objects of representation from ‘popular’, ‘parliamentary’ and sometimes ‘national representation’ in an age of parliamentary reforms to ‘democratic representation’ in the twentieth century.

Figure 1. Hansard at Huddersfield (2019). “Popular/democratic/representative/parliamentary government, 1803-1900” [Figure]. University of Huddersfield. Available from: https://hansard.hud.ac.uk.

Figure 2. Hansard at Huddersfield (2019). “Popular/democratic/representative/parliamentary government, 1901-2020” [Figure]. University of Huddersfield. Available from: https://hansard.hud.ac.uk.

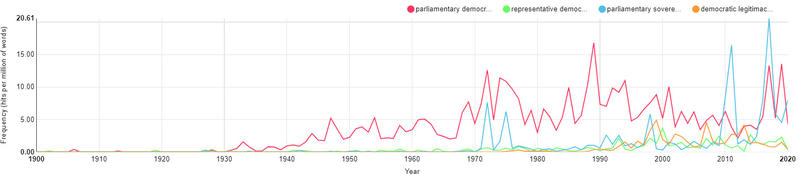

The transitions demonstrate the relatively short history of democracy as a parliamentary concept, something that historians of earlier eras should keep in mind. The bigrams suggest that it was first Nazism (like in the Nordic countries) and then European integration, the fall of the Eastern bloc and devolution within the British polity that provoked waves of discourse on ‘parliamentary’ and ‘representative democracy’. It has been only since EEC-membership and the 1990s that ‘parliamentary sovereignty’ and ‘democratic legitimacy’ have been debated more intensively and explicitly – in the context of devolution, a parliamentary expenses scandal and the Brexit referendum (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Hansard at Huddersfield (2019). “Parliamentary/representative democracy, parliamentary sovereignty and democratic legitimacy” [Figure]. University of Huddersfield. Available from: https://hansard.hud.ac.uk.

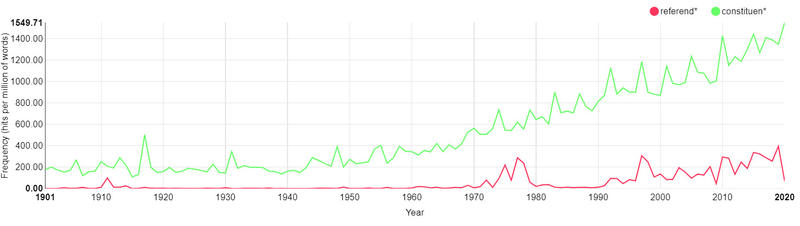

Simultaneously with more open reflections on the sovereignty and legitimacy of parliament, British MPs have also referred to their ‘constituencies’ and ‘constituents’ more frequently than ever before, which suggests that they have become more responsive to the voters. Remarkable is how the preceding terms for the representative political system have been at times totally eclipsed by references to ‘referenda’ -- first around 1975 and again between 2013 and 2019 (Figure 4). As Justice Secretary and Lord Chancellor Robert Buckland (Con.) put it in 2019: “It is time for all of us who believe in representative democracy to accept the fact that the whole concept of parliamentary representation is itself on trial.” A question we need to ask is whether such discourse on the crisis of representative democracy is a purely British phenomenon or whether similar trends are visible in other Northwest European countries as well.

Figure 4. Hansard at Huddersfield (2019). “Referend* and constituen*” [Figure]. University of Huddersfield. Available from: https://hansard.hud.ac.uk. NB the radically higher frequencies compared to the terms discussed above.

It may be that the fragmentation of older identities and the rise of individualistic discourses supported by the new media are changing parliamentary institutions in historic ways. If that is the case, it is ever more important to investigate the early modern roots and the modern evolution of parliamentary institutions. It is worthwhile to do that by appreciating the concepts used by parliamentarians themselves, by making use of the big data tools in our possession to analyze their meanings, and by comparing national parliaments and considering cross-national transfers between them – by writing entangled histories of parliamentary institutions.

Pasi Ihalainen, Academy of Finland Professor, University of Jyväskylä.