‘Proximity’ and the Continuities in Parliamentary Representation

In the history departments of many European countries, a division of labour exists between early modernists and modernists. Historians specialize in either the one or the other period. Since at least the 1980s, this practical subdivision of the discipline has been reinforced by historiographical developments. The French Revolution had always been seen as a watershed, but modernization theories and nationalism studies have turned the watershed into an almost absolute rupture. The revolutionary period was when modern politics and modern nations were invented. Even if some would argue that the real breakthrough of modernity was at the end of the nineteenth century, or that the ‘birth of the modern world’ was a protracted process over the whole of the ‘long’ nineteenth century (1780-1914), the effect is the same: modernists turned their back on the early modern period. What happened in the early modern period was not decisive or perhaps not even really important for modernists, since they had to deal with different issues, demanding different perspectives and methods. The modern period appeared to them as a new beginning.

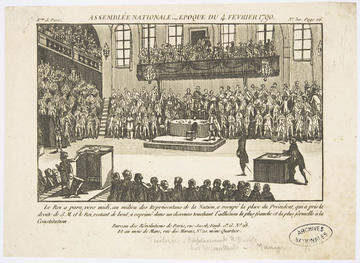

Engraving of the proceedings of the French Assemblée nationale in 1790, from: Archives nationales AE/II/3878. Wikimedia Commons.

The popularity of this idea perhaps reached its peak in the years around the bicentennial of the French Revolution, in 1989, which also saw important new work on the National Assembly, the first modern French parliament, by André Castaldo and Timothy Tackett, among others. The new attention to the culture of politics – the Revolution was now first and foremost seen as the emergence of a new understanding of politics and a new political culture – stimulated interest in parliamentary rhetoric and in parliamentary publicity, which was seen as typical of the modern age. There was no denying, of course, that 1789 and subsequent years saw many innovations. What were called ‘parlements’ in the French ancien régime were not the same as parliaments in the nineteenth century, and were closer to a law court than a representative assembly. The whole idea of ‘representation’, especially, seemed to have changed completely. Whereas the early modern estates defended the provinces and towns before the lord of the country, the French National Assembly was supposed to act as a sovereign in the national interest. This was a new world, was it not? No serious historian would deny that there were connections with the world before 1789, but it was the radical innovations that interested historians most.

The Dutch States General in 1639, creator unknown, London, 1639. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

France is the most famous case of a rupture between the early modern and the modern age, but was it that much different in other countries? Take for example the Netherlands. The Orange family had been connected to the Netherlands since the beginning of the Dutch Revolt in the sixteenth century, but after the fall of Napoleon and the end of their exile, they returned in a new role, not as Stadtholders but as Kings. To this day, the two chambers of the Dutch parliament are called the ‘States General’, the name given to the old regime institution that had ruled the Dutch Republic from the late sixteenth century until 1795. In 1964 five hundred years of States General and an ‘ever more perfected popular representation’ were celebrated. Does this indicate any genuine continuity between the different institutions? Dutch historians have dismissed the claim of continuity between early modern and modern forms of representation as a case of invented tradition, the result of a Dutch version of the Whig interpretation of history in the nineteenth century in which the discontinuities were papered over. Their reappraisal of the period around 1800 suggested that this was when the foundations for modern politics and the modern state were really laid.

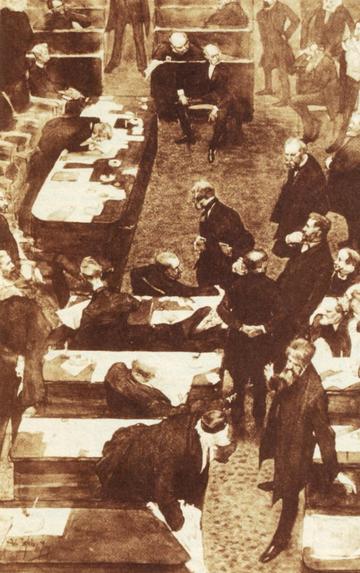

The Second Chamber (Tweede Kamer) of the States General (i.e. the Dutch House of Commons) in 1887, picture by Pieter Josselin de Jong. Wikimedia Commons.

However, that was not the end of the story. Recently, the attention to continuities has grown again amongst historians in many countries. Was the role of court of appeals, which some senates still played in the nineteenth century, not reminiscent of the function of the regional French ‘parlements’ in the eighteenth century? Should historians, in a wider sense, not investigate the likely influence of an older political culture on modern political practices? Not in order to deny innovations or real discontinuities, let alone advocate complacent conservatism, but to do justice to the long-term effects of cultural habits. In the Netherlands, it turned out that, despite the obvious and glaring institutional discontinuities, the old meeting practices of the States General had a lasting effect on the sober rhetoric and administrative flavour of nineteenth-century Dutch parliamentary politics. Moreover, although institutions and representation came to be attached to the national, rather than the provincial level, practices of the representation of local and regional interests survived and persisted throughout the nineteenth century.

From the British perspective, these continuities may not come as a surprise, since British parliament has not known the ruptures of continental parliaments, has cherished Burkean ideas of representation since the eighteenth century, and has retained a strong notion of local engagement by MPs. Still, the weaknesses of the Whig interpretation show that it is easy to overestimate continuities.

The recent brutal murder of the Conservative MP David Amess has put the exceptional, although not completely unique, British habit of constituency surgeries or interviews at the centre of international attention. As Paul Seaward has suggested, this habit started to grow a century ago – probably, I would think, as an accompanying feature of democratization. Under the conditions of general suffrage, the worries of ordinary people counted and should be taken care of. The surgeries are a very practical element of an MP’s calling. They tie in with what, at a very theoretical level, French political historian and philosopher Pierre Rosanvallon has called the longing for ‘proximity’ among voters: politics not as a distant, abstract matter, but as a practice that is relevant for their own lives, and that belongs to ordinary people, too. Rosanvallon argues that this longing is typical for the contemporary age. I doubt that. It seems to me that this is a perennial feature of politics, but that its form has continually changed. To see this, it helps if we abandon the old idea that (parliamentary) ‘representation’ changed around 1800 from representation of local particular interests to representation of the general interest. It has probably always been both. This may be more difficult to see in France or the Netherlands, where the rupture with the ancien régime seems more radical than in Britain, but even in Britain, Edmund Burke’s famous description of the role of the MP – not a member for Bristol but a member of parliament – has often been used to describe or advocate a distinctively modern conception of parliamentary representation. That Burke was clearly also promoting the interests of Bristol and those of important private persons from his constituency has often been ignored or seen as a mere practical and biographical, if not opportunist, aspect of his politics. It is true: Burke did not sit every week for a surgery, and if he promoted the interests of individual people, they may have belonged to the privileged class of voters or the local elite. Even for him it was apparently self-evident to take local interests into account, and not choose between either the general or particular interests. Proximity counted for him, too.

Statue of Edmund Burke on Colston Avenue, Bristol, in 2012. Wikimedia Commons.

Today, the surgeries stand out as a sign that politics should be concerned with individual constituents and their interests. This is more than a compromise with the practices of ordinary people who could not fathom the general interest: it is a crucial element of politics. In his analysis of American democracy, Alexis de Tocqueville came to the conclusion that it was an advantage for the development of democracy that local politics started in your own backyard. Local communities were the basis for healthy politics. You needed the engagement and participation that only local politics could provide for everyone. This is common knowledge for many early modernists, such as Maarten Prak. His Citizens without Nations, about citizenship in the world of early modern towns in the Low Countries and elsewhere, argues that local citizenship could make politics more democratic than the distant modern representative system. Perhaps we should conclude that in order to have fair, democratic politics, we need to distinguish between particular and general interest, but we also need to connect them in some way. To see how this could be done, historians of the modern age should profit from the work by early modernists. Rather than interpreting the history of politics as a development from particular interest (a form of proximity) to a more distant general interest, it should perhaps be seen as a process of continuously calibrating the two.

Henk te Velde, Professor of History, Leiden University.