Re-imagining Democracy and the Parliamentary Cultures Project

During the past fifteen years, I’ve played a leading role in an international collaborative project looking at the process of ‘re-imagining democracy’: that is, the process of taking this ancient word, with ancient associations, and refitting it for modern use. We suggest that this process mainly unfolded in the later eighteenth and first two thirds of the nineteenth century. By the end of that time, the word had well-established modern referents, and was becoming a routine item in the lexicon of everyday political life, though its meanings and uses continued and of course continue to change. This project has so far given rise to two books: one looking at the North Atlantic (America, France, Britain and Ireland) the other at the Mediterranean (Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece and the Ottoman world). We’re now working on a third, on Latin America and the Caribbean, which we hope to submit for publication early in the new year. A fourth and final book, on ‘central and northern Europe’ – the realms of Germanic, Slavic and Scandinavian languages – is in prospect.

Why focus on a word? We decided to make the word central in order to avoid teleology. In the past, people did not assemble in quite the same way the concepts, aspirations and institutional templates that someone now might assemble under the name of ‘democracy’. We don’t think it’s helpful either to measure up the past against these constructs (which are themselves subject to change) or to disaggregate them and trace the histories of their components (though that approach has a bit more to recommend it). Instead, we set out to look at how people in the past talked about ‘democracy’, and what work they used the concept to do – because we think this puts their understanding and their actions in central focus. Of course, that means we’re not writing the history of any single project: the story we tell jumps around a bit. But, from our experience of applying this approach, we do think that it provides an interesting perspective on changing and varying aspirations and practices, loosely associated with two core ideas. As we expressed those in our first book: ‘that no one person is intrinsically worth more than any other person, and that everyone should have a voice in shaping the rules that enable us to live together.’

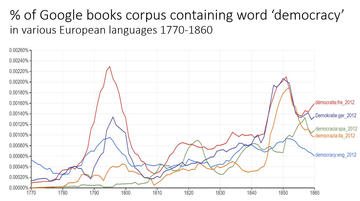

Google Ngram charting the uses of the word democracy in various European languages, 1770-1860.

The Re-imagining Democracy project stands at an angle to the Recovering Parliamentary Culture project for two main reasons. First, because it focusses on a different, somewhat later time period. It would be possible to argue that the Re-imagining Democracy project starts too late: the word gained a place in many modern European vernaculars before the end of the seventeenth century, and during that century, was sometimes employed, not just in scholarly writing, but in real live political argument. Yet (we report) the first French Revolution enormously raised the profile of the word (while also reinforcing existing negative connotations), and during the middle decades of the nineteenth century it became mainstream, a name which people of many ideological shades sometimes saw merit in appropriating for their own causes, while from this time democracy was increasingly identified as the necessary form of modern governance (even though it remained contentious how, and indeed whether it could be given stable and constructive institutional embodiment).

A second reason why our project stands at an angle to the Parliamentary Culture project is less obvious. In the present, ‘democracy’ is understood by many to be intrinsically and importantly linked to parliamentary culture (though plebiscitary democracy is also rising in favour). The association between ‘democracy’ and representative institutions was much weaker in the past. Parliaments, estates systems and so forth could be conceptualised as democratic elements within ‘mixed’ systems of government. But ‘democracy’ was also sometimes used as a name for a greater whole, effectively a synonym for republic: a state oriented to the common good. Or it was taken to characterise any state channelling the people’s will, perhaps through an authoritarian leader. Or it was associated with extra-parliamentary culture. Estates bodies (with some reason), and later (perhaps more surprisingly) elected representatives, were, indeed, sometimes conceptualised as aristocratic.

Granted that our project is at an angle to the parliamentary culture project, nonetheless, work that I have done setting the background to our project, looking at the early modern period, does suggest to me some observations and questions.

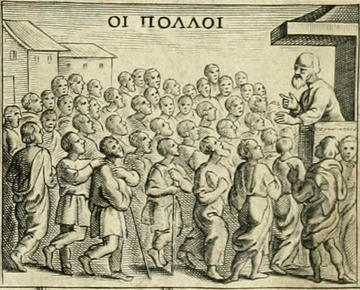

The people and a demagogue. Detail from the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’s 1634 translation of Thucydides, from Eight Bookes of the Peloponnesian War, Wikimedia Commons.

My first observation and question arise from a chapter that I recently wrote for the Bloomsbury Cultural History of Democracy, vol. 5, 1650-1800 (2021). In that, I tried to contrast ways that people talked about ‘democracy’ in a practical political setting at the start and end of the timespan covered by the book: around 1650 and around 1800. My impression, from some admittedly hasty and shallow research, was that in 1650 the word was recurrently applied to intermediate bodies, poised between rulers (usually monarchs) and people: such bodies being characterised as democratic elements within government. By 1800, though, the word more rarely meant those bodies alone. More often it carried with it the implication or expectation that such bodies, in order to be democratic, must be aligned with and responsive to the people out of doors; the expectation was that the people at large must be truly empowered for an institutional arrangement to qualify as democratic, and experiments were undertaken to find ways of empowering them. That’s the observation – open to challenge and correction. My question is, in the seventeenth century, what lexicons were employed when people spoke or wrote about the relationship between members of parliamentary bodies and the people at large – or what were already in England at least termed their ‘constituents’, given that these interactions were not being characterised as central to the functioning of ‘democracy’. Parliamentary culture surely wasn’t constituted only by relationships among parliamentarians. How were their relationships with wider publics represented, and how did their substance and the terms in which they were discussed vary from place to place, as well as from time to time?

Baruch de Spinoza, in his unfinished Tractatus Politicus, conceptualizes aristocracy and democracy in terms of access to office, from Tractatus Politicus, published in Opera posthuma, Amsterdam, 1677.

I was also struck in my reading for that chapter (though I didn’t make much of it in the piece) by an alternative seventeenth-century understanding of what a ‘democracy’ was – an understanding certainly warranted by Aristotle’s account, though one that would later drop from use. That is, that it was a system of government in which commoners, or ordinary people, were eligible to hold public office. Here is a conception of what it might mean for the people to take part in ruling that did not entail any requirement that the person in question should operate as any kind of delegate; such people ‘represented’ the people at large only in the sense that they originated among them. That’s my second observation. The related question is, to what extent and in what ways was being a member of one of the parliamentary bodies under scrutiny in this project conceptualised in terms of holding a public office, and, as such, akin to holding other, for example executive offices? What ideas, representations and practices sprang from that association, or need to be interpreted in its light?

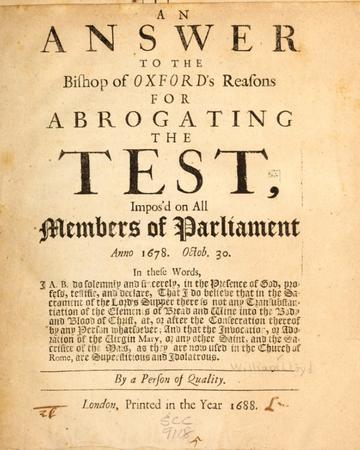

My third and final observation and question don’t relate to the history of the word ‘democracy’ but rather to my readings in mid seventeenth-century English primary sources about qualifications either for voting or for holding office. Whereas modern commentators on these sources have often been mainly concerned with qualifications relating to status or property, possibly also to gender or age, what often strikes me is that in the sources themselves those issues may be dwarfed by concerns about people’s political reliability. How to ensure that rights to choose or serve are vested in the right-thinking and loyal was often the main consideration, sometimes the subject of pages of discussion, which historians sometimes disconcertingly skip over to focus on what is said about status. Here’s a case where more modern preoccupations seem to frame the narrative – though actually, keeping the disloyal out of power has often been a preoccupation in the modern world too, thus during the French revolution, in the aftermath of the American Civil War and in post-war Germany, to name only a few of many possible examples. My question arising from this observation is, when, where and how did concerns about the loyalty of members of parliamentary bodies manifest themselves in the bodies to be studied here?

Religious and loyalty ‘tests’ for officeholding were controversial in England until the early nineteenth century, from An Answer to the Bishop of Oxford’s Reasons for abrogating the test, impos’d on all members of Parliament anno 1678. Oct. 30., anonymous author, London, 1688.

I expect that the directors of this project will be sympathetic to the tenor of my observations and questions. They will probably agree that, though ideas arising from modern political cultures can help us to frame questions and to interpret the past, at the same time we need always to be careful not to see the past only through lenses provided by the present – while also keeping in mind the heterogeneity of ideas and practices in the present. Sometimes the past is best illuminated by under-noticed elements of the present, and can in turn illuminate them.

Joanna Innes, Professor Emeritus of Modern History at Somerville College, Oxford.