Recovering Europe’s Parliamentary Culture, 1500-1700

The authors of this blog may have a claim to the invention of the concept ‘early modern parliamentary culture’. A simple Google search produces only three results, and none of them defines the concept, let alone placing it centre stage. Which is odd, given that political assemblies – parliaments, diets, states, estates, Sejm, Cortes, Riksdag – were common in late medieval Europe and have long been a staple subject of national and international historiographies focusing on the big themes of power and its distribution. But while the cultures of the other major institutions which structured political life – notably monarchies and royal courts – have been the subject of intensive and transnational study, the culture of parliaments, the ideas, habits of mind and routine practice which shaped them, is usually passed by. We believe that by bringing the tools of intellectual, transnational and cultural history to the study of parliaments, we can begin to transform the way in which we think about early modern political institutions.

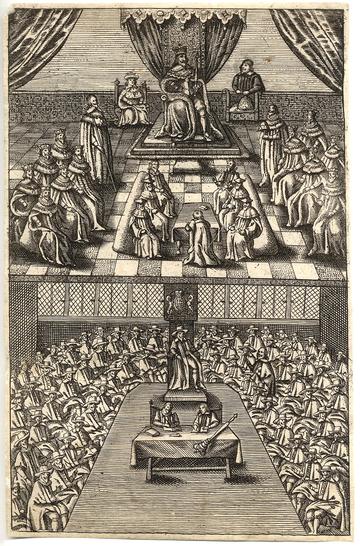

Polish Sejm, in Jan Łaski Statute, Commune incliti Poloniae Regni priuilegium constitutionum et indultuum publicitus decretorum approbatorumque (Cracouie, 1506).

First, through intellectual history. Intellectual historians of the early modern era naturally think in terms of concepts – representation, republicanism, absolutism – rather than institutions. And while they have recognised the importance of understanding the context within which those concepts are wielded as moves in current political arguments, the dominant legal-constitutional approaches to parliamentary history and nation-specific scholarly traditions have, perhaps, tended to put off intellectual historians from thinking more closely about the institutional contexts in which they are wielded.

But political assemblies, especially when they play the role of representative institutions, are at the centre not only of politics, but also of how politics is conceived. They function in the social world and are shaped by language and discourse; and yet they also shape it. The rich and eclectic political language of early modern Europe, indebted to classical antiquity for many of its concepts, categories and comparisons, was deployed to describe or to criticise these existing institutions. What marked the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm in the eyes of Jean de Monluc, the leader of the French envoys promoting the election of Henry Valois to the Polish throne in 1573, was its uprightness and freedom. Addressing the Polish senators and noble delegates whose favour he sought, Monluc stressed that their large assemblies, to which so great a multitude of nobles were accustomed, had always been free from the corruption endemic to Roman assemblies. And upon his election, Henry was required to promise the nobility of Poland-Lithuania that he would convene a general Sejm at least once every two years for six weeks and to acknowledge that as king he had no right to impose new taxes without approval of the Sejm. Thereafter, an oath to uphold these provisions, called the Henrician Articles, was required of every king-elect. The Sejm, composed of the king, the senate and the house of delegates, thus became a constitutionally guaranteed institution, and was situated at the centre of the political life of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Discussion of politics was steeped in, and centred around, its existence.

Something similar might be said of England or of the Netherlands: there has been a lively debate about the existence in England of republicanism, or ‘monarchical republicanism’, and participatory politics in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. This debate is placed remarkably rarely in the context of a vigorous, and intensifying, parliamentary culture. Yet, when thinking about how politics worked, people were thinking as much about interactions in political assemblies as they were of the limited circles of courtly counsel.

Interior of the Great Hall on the Binnenhof in The Hague, during the Great Assembly of the States-General in 1651 (c. 1651) attributed to Bartholomeus van Bassen, Mauritshuis, The Hague.

Second, through a transnational history of parliamentary cultures. Parliaments take different legal forms and different shapes throughout Europe. There are assemblies where the different classes or estates meet together; there are assemblies in which they meet in separate chambers. There are assemblies which consist of delegates of practically sovereign entities; there are assemblies which are directly elected by relatively large bodies of people. There are assemblies whose determinations have the force of law on any subject; there are assemblies which do little more than offer advice, or are brought together just to agree to financial exactions. These distinctions have often dominated discussion, and left us with an impression of infinite variety, and a sense that little can be gained from the comparison of these different bodies.

But this has obscured a bigger picture of a common culture, in which assemblies across Europe operated in similar ways and faced similar pressures. During the ‘Long Reformation’, roughly between 1500 and 1700, all of Europe’s political assemblies encountered transformative change. Many became both site and subject of urgent debates about religion, the royal succession, and the relationship between monarchs and subjects.

Members of European assemblies were not only political actors but also political thinkers, divines, historians, and imaginative writers. In seeking to understand the changes and the conflicts they dealt with, they and others reflected on their own institutions and compared them with foreign ones about which they learnt firsthand, or from diplomats or travellers, or from books. They recognised a common inheritance from their Roman, post-Roman and ecclesiastical counterparts: they developed a comparative procedural political science, founded in the admiration and emulation of Roman or Venetian institutions. They shared common languages of national and institutional privileges and freedoms, of proceedings by precedents and customary rules; a common concern with rhetorical culture; common practices of record keeping, of engagement with questions of publicity and secrecy. Quasi-parliamentary assemblies were transplanted beyond Europe, to the Anglophone colonies of the Caribbean and of North America, and continued to look to Europe’s, particularly to England’s, parliamentary culture. Yet we continue to think of parliaments as above all specifically national institutions. There is an ever-proliferating literature on political, legal, diplomatic, and civic culture. But no attempt has been made to reconstruct this rich transnational parliamentary culture or to chart its change over time.

And finally, through a recognition that parliaments lie at the intersection of so many aspects of the lives of the territories and populations they aim to represent. It is not just in political assemblies, of course, that people from all geographical corners of an early modern political society routinely came together to transact business: royal courts and legal tribunals, even, to a lesser extent, commercial exchanges, are also places where connections are made and conflicts played out and (sometimes) resolved. But it is only in political assemblies that they do so in a way that is claimed to be explicitly reflective or representative of and responsive to, a population as a whole.

That claim can of course ring hollow. While their aim is in some sense to be inclusive, metaphorically to bring together a whole people, representative political assemblies may also explicitly exclude some (such as Catholics, in England after the imposition of the oaths of allegiance and supremacy). And, while they treat non-voters – including virtually all women – as implicitly incorporated in the community, their physical absence means the absence of many of the preoccupations of a large proportion of it.

But compromised though the system may have been, and ambiguous as the concept may be, those who were sent to a diet or parliament or Estates recognised a responsibility to represent their communities in a way that brought together in an exhaustive and exhausting period of physical interaction the multifarious activities of the inhabitants of a political entity. Those they represented had high expectations that they should articulate their grievances, or intervene in their problems. Everyone who could, watched: the meetings of these assemblies are among those moments when a lot happens.

Charles I in the House of Lords, and the House of Commons, frontispiece from, ‘An exact collection of all remonstrances…’ (London, 1643).

This is not simply that parliament is a ‘point of contact’ between court and country, in G. R. Elton’s famous phrase about the English parliament of the sixteenth century – although the characterisation is perfectly valid. It is that meetings of political assemblies are where the institutions and political structures of a country, and the aspirations and fears of its inhabitants all meet: court and country, city and country, church and the secular state, reformers and anti-reformers, absolutists and democrats. They react to and communicate with the nation’s culture at all levels.

We hope in this blog series to open up new ways of approaching parliaments and other consultative and representative institutions. We hope to view them not simply as legal and constitutional structures, and not just as the stages for the political competition either of individual politicians or of social forces, but as these extraordinary intersections of political and other cultures. We want to think about them as cultural phenomena, a focus of attention that is reflected in drama and other literary works, as well as in buildings, archives and rhetorical practice; as ideas, to recognise that they are themselves political concepts of key importance in the formation of states and the modern mind; and as a European phenomenon, shared and discussed as a common intellectual inheritance across the continent. The blogs will run alongside a pilot project which will compare the Dutch States-General, the English Parliament, and the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm – the period’s most robust national assemblies. And ultimately, we hope, they will encourage a broader interest in these phenomena, and everything that they represent.

Paulina Kewes, Jesus College, Oxford

Dorota Pietrzyk-Reeves, Jagiellonian University

Paul Seaward, History of Parliament Trust