Representation without a Parliament: How Latin America’s Colonial Cities Thrived without Cortes

When the future Charles I arrived to be proclaimed King of Castille in 1518, he was presented before the Cortes assembled in Valladolid. Back then, the Cortes still consisted of the three estates – Clergy, Nobility and the Commons represented by the cities. The occasion was of major importance, for the Cortes would swear in Charles as their new sovereign. Charles had been born in the Flemish city of Ghent and this was the first time he had set foot in Castille. He barely spoke the language and his entourage was composed entirely of Flemish courtiers with little comprehension of the Peninsula’s political culture. Therefore, it was expected that the Cortes should remind the new King – and later Holy Roman Emperor – of his main duties as sovereign. A representative from the cities took the stage and started the lesson. The new king was expected simply to “rule well”, and, as was explained to him, “to rule well is to dispense justice, giving to each what is owed”. Charles should not forget that he was linked to his people through a “tacit contract” that required him to “keep a watchful eye on his subjects while they sleep”. The lesson ended with a powerful metaphor: the King was “a mercenary of his vassals”. In essence, the cities assembled in the Cortes would impress on Charles that his power as king was conditional. It emanated from the kingdom – represented by the cities – and was transferred to him through an unwritten and unbreakable pact.

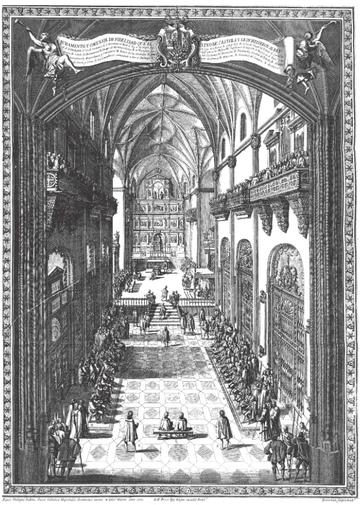

Philip V is received by the Cortes in Madrid, 1701", from Antonio de Medina y Ubilla, “Sucesión del Rey don Felipe V a la Corona de España”, 1704. Biblioteca Nacional de España.

The Castilian political system of the 16th century relied on a balance of obligations and privileges between the cities (as autonomous political bodies) and the King (as the source of justice). This relationship was based on an individual negotiation between the cities – that is to say, the city councils which made political decisions on behalf of urban interests – and the Crown, with the latter obliged to be sensitive to local particularities, acquired privileges, and traditions. The Cortes, since 1538 the assembly of 18 cities without the clergy and nobility, was a central actor in this negotiation of power. A long tradition of Castilian urban culture, starting in the early Middle Ages, had led to an institutionalization of political representation through the Cortes. Each city represented in the Cortes discussed the main problems of the Kingdom locally, after which their decisions were communicated to the assembly by two procuradores (representatives). The Castilian cities were, in fact, the stage on which political consensus was negotiated and renewed.

However, when the Spanish colonial system in America developed, this Castilian parliamentary system was not exported. Even important cities such as the viceregal capital Mexico City, or Lima capital of Peru, were never represented in the Castilian Cortes. Although proposals to create a common body of representation for all the cities in Latin America were made in 1559, 1570 and 1609, these were never seriously considered – neither by the Council of the Indies (the major governmental institution for Colonial Latin America), nor by the King, nor by the cities back in Spain. The reasons for this refusal lie beyond the institutional framework of the Spanish Empire. Although there was no institution that represented all the cities in the New World, each one found ways of defending their interests at the Court in the Old World.

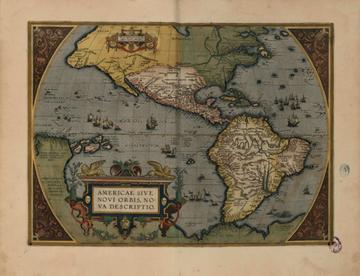

Map of Latin America (1570), from Abraham Ortelius, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, 1570. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid.

To understand this peculiar system of representation, we must consider its genesis. How was the balance of political power established from the outset of the Spanish Empire, and how did it shape political culture? After 1492, and especially since around 1510, the Spanish political system in Latin America was constructed on the basis of the cities. During the 16th and 17th centuries there were around 200 new urban foundations in the continent, each of them with their municipal government and capacity for self-representation. This fast urban development resulted in what can be labelled as an empire of urban republics, reflecting the strong autonomous nature of cities within the Spanish Monarchy. Cities created and extended their own jurisdiction on the ground through their capacity to “pacify” indigenous populations and, therefore, accomplish one of the main objectives of the monarchs: the conversion of indigenous peoples to Christianity. Cities incorporated indigenous people in their communal lives by involving them in urban “conversation”, a feature of the civic communities adapted from the classical concept of civitas. This ability of cities to promote the conversion of indigenous people helped them to defend their jurisdiction, and their capacity to exercise political and legal power. Its extension equated to the extension of empire itself: as new cities were founded, more jurisdiction was created, and more power could be claimed. Cities did not just represent royal power on the ground; in fact, cities were themselves the power on the ground.

This state of affairs was beneficial for both the newly created cities and the crown. The latter did not perceive this urban development as a loss of its sovereignty. Quite the contrary: cities generated political power on the ground, and would later feed the King’s sovereignty. Helen Nader brilliantly defined this system as “the more [numerous/powerful] the communes, the greater the king”. Therefore, the Crown encouraged the foundation of more urban centres, thus expanding its capacity for control and conversion of the indigenous population. The cities and their citizens (vecinos, literally ‘neighbours’) were highly aware of their own importance within the system and constantly demanded, and almost always obtained, fiscal, economic, or labour benefits from the King. Each city engaged in individual negotiations with the Crown, thereby counting on their leverage as the actual bearers of jurisdictions.

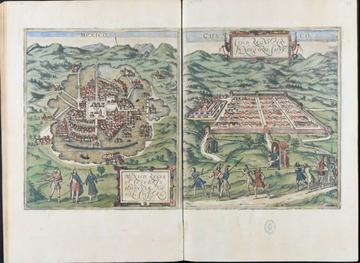

Map of Cuzco and México (1575), from Georges Brum, Civitates Orbis Terratum, 1575. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid.

This individual negotiation was accomplished through the dispatch of procuradores from the city to present their demands at the royal Court in Spain. No matter how small a local community was, it would be ready and willing to send an ambassador to the Peninsula. These emissaries would transmit to the highest levels of the imperial administration the demands agreed on by their local councils, and would ask the King for his grace in conceding them. In 1534, the city of Acla, founded in 1514 in the eastern limit of the Isthmus of Panama, had fewer than 200 inhabitants. Their presence in the territory had allowed a fluid and peaceful commercial relationship to develop with different cacicazgos of the area. For that reason, the city had been attacked by a rival Spanish town which had brought the city to the brink of depopulation. In this context, the small, but proud, city dispatched a procurador straight to Madrid. This urban representative acted in the name of the whole “republic and its citizens”, defending their privileges and seeking protection from the Crown. As Acla was the oldest town in the region, it was the key to maintaining the peace with the indigenous populations and, therefore, maintaining the colonial jurisdictional claim in the area. Typically enough, the King granted all the demands of the emissary to avoid potentially serious problems in a strategic region of the Spanish Empire. As in this case, no matter how small a city or town was, it could receive attention and obtain benefits from the Crown. These urban settlements formed an interconnected system of republics within the Spanish Empire.

This explains why neither the Castilian cities nor the Crown were ever really interested in creating a common body of representation like the Cortes for Latin America: there was simply no need. Castilian political culture had the instruments to allow for an effective representation of overseas cities beyond the institutional framework of the Cortes. The cities could keep their relationship with the Court on an individual basis and obtain more benefits without intermediation. In Castile only the 18 largest and most prominent cities were represented in the Cortes and they had limited political influence. Every colonial city, by contrast, had the real capacity to reach the Court and present their individual business directly. To ensure that they survive and keep jurisdictional control of the continent, the King continued to grant privileges to these cities. Even if it was tacit, and outside the institutional structure of the Cortes, the contract between the Crown and the American cities as individual corporations within the empire is the central instrument that facilitated over 300 years of colonial control in Latin America. Given the benefits that all the political stakeholders obtained from a more informal and individualized form of representation, there was no need for representation through the Cortes.

Jorge Díaz Ceballos, Postdoctoral Researcher, Universidad Pablo de Olavide.