Revolution, Republicanism, and the End of Empire: Latin America in Victorian Intellectual History

Nineteenth-century Latin America was one of history’s great political laboratories. The post-revolutionary successor states of Spanish America, inheriting the shell of a defeated seaborne empire, conducted an extraordinary range of oligarchic, constitutional, and dictatorial experiments. Independent Brazil pursued a parallel series of studies in monarchical, imperial, and ultimately republican rule. Along the way, the region generated reams of evidence which could be used to support or to contest contemporary political and social theories. Historians of Spain, France, and the United States have been attentive to this dynamic for some time. But Latin America’s impact on intellectual culture in Victorian Britain—the great engine of European Liberal thought, and of trans-Atlantic ‘informal imperialism’—remains obscure.

Accounting for this historiographical blind spot is easy enough. Work on Britain’s ‘informal empire’ in Latin America has tended to treat it as a robustly practical enterprise, driven by appetites for trade, influence, and profit, in which ideological claims played a strictly limited role. Historians of Victorian ideas about global order have, accordingly, concentrated on regions which seemed to raise more profound questions, mainly Europe, the United States, and the ‘formal’ empire. This piece suggests that nineteenth-century British arguments about Latin America need to be taken more seriously. Not only do they provide new angles on most of the Victorian era’s headline debates about government and societal order, but set in their international contexts, they indicate that nineteenth-century historians may need to think differently about the forces which shaped European attitudes towards the wider world.

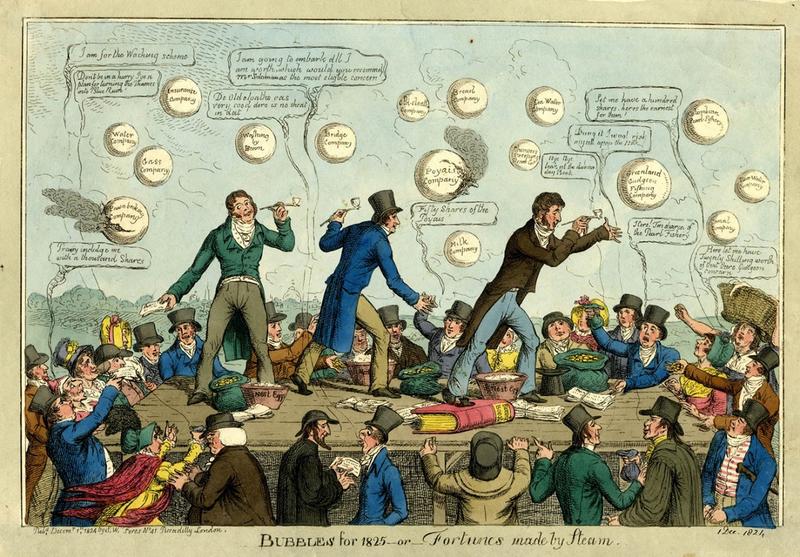

A satirical representation of the superheated speculative atmosphere in Britain in the mid-1820s, which was driven in significant part by Latin American investments and loans.

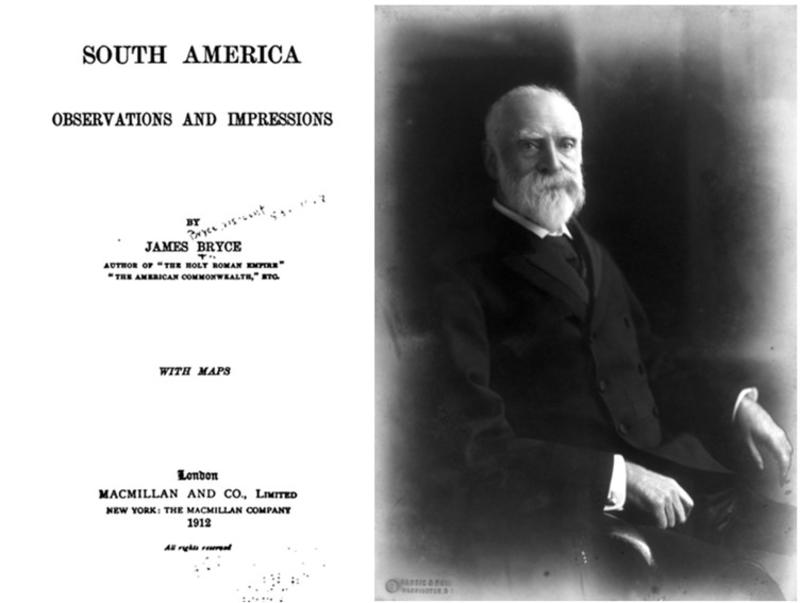

For historians preoccupied with the most rarefied reaches of nineteenth-century British intellectual culture, first of all, Latin America is unquestionably a topic which demands more attention. It is well known that, among the luminaries of the age, Jeremy Bentham and James Mill were seriously interested in Spanish American independence. It is less often observed that they were far from alone. In fact, nearly all the most celebrated political thinkers in Victorian Britain used Latin American evidence in support of wider arguments about modern politics and sociology. A tour of collected works is instructive. Liberals especially were prone to reflecting on the region—all the most prominent usual suspects can be ticked off in this connection, including J.S. Mill, T.B. Macaulay, Walter Bagehot, Lord Acton, Herbert Spencer, J.A. Hobson, and (in the Edwardian years) James Bryce—but so too can Conservatives including Lord Salisbury, Positivists including Frederic Harrison, and uncategorisables like Thomas Carlyle. These figures contributed to a vastly larger mass of analytically ambitious elite and middlebrow commentary on Latin American matters, spread between periodicals, pamphlets, newspapers, tracts, histories, institutional anatomies, memoirs, and travel literature.

Among other accomplishments, the Liberal politician and intellectual James Bryce was one of the great (post-) Victorian interpreters of South America.

This interest in Latin America is hardly surprising. Developments in the region had obvious consequences for many of the most pressing questions in nineteenth-century British political and social thought. Spanish America’s revolt against Spanish colonial rule was one of the most spectacular revolutionary episodes of modern times, and became a central piece in later attempts to puzzle out the causes and consequences of modern revolutions. In the same connection, Latin America offered the great contemporary example of imperial decline and fall, and in the case of Brazil, of the translation of a colony into a (self-proclaimed) empire. After the 1820s, moreover, most of the world’s republics were concentrated in Spanish America. Working out why so many of them seemed so unstable involved entering into virtually all the era’s major debates about government and political economy, not to mention thinking about the role played by the United States in the region, and about the diffusion of North American values and ideas. Arguments about the condition of Latin American republicanism, in turn, raised even wider questions about how best to secure social progress in less developed (and sometimes Roman Catholic) communities. Discussion of all these problems was partly reflective and theoretical, but for many in Britain there were hard-to-miss practical implications in relation to Ireland and the colonies, especially when it came to the forces accelerating the ends of empires. In addition to all this, there were numerous efforts to conceptualise and rationalise what Britain and other European countries were seeking to achieve in their nineteenth-century intercourse with Latin America. That is to say, there is also a substantial intellectual history of ‘informal empire’ to recover.

Articulate interest in post-revolutionary Latin America tended to be organised around more spectacular regimes, figures, and developments, as was typical of nineteenth-century British engagement with the wider world. Any number of high-profile case studies might be picked out. In the 1820s and 1830s, the uniquely rigorous dictatorship erected in Paraguay by Dr José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia—later made famous by Thomas Carlyle—was adopted as a mascot by British commentators who sought to assert the superior merits of ‘order’ over ‘liberty’, and who considered themselves properly attuned to the gritty realities of imperial power. Their claims contributed to broader disputes about the character and merits of the distinctive, militaristic, personalist form of caudillo government which took hold across much of independent Spanish America. In the 1850s, commentary on the war between the Argentine Confederation and the secessionist State of Buenos Aires anticipated some of the British debates over the US Civil War.

Dr José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia, Dictator of Paraguay, the subject of a celebrated 1843 essay by the historian Thomas Carlyle.

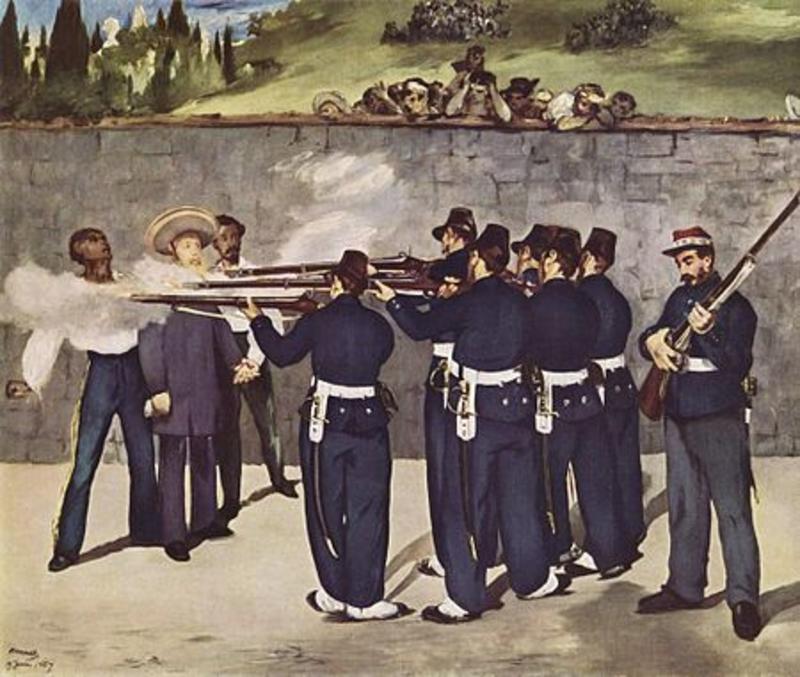

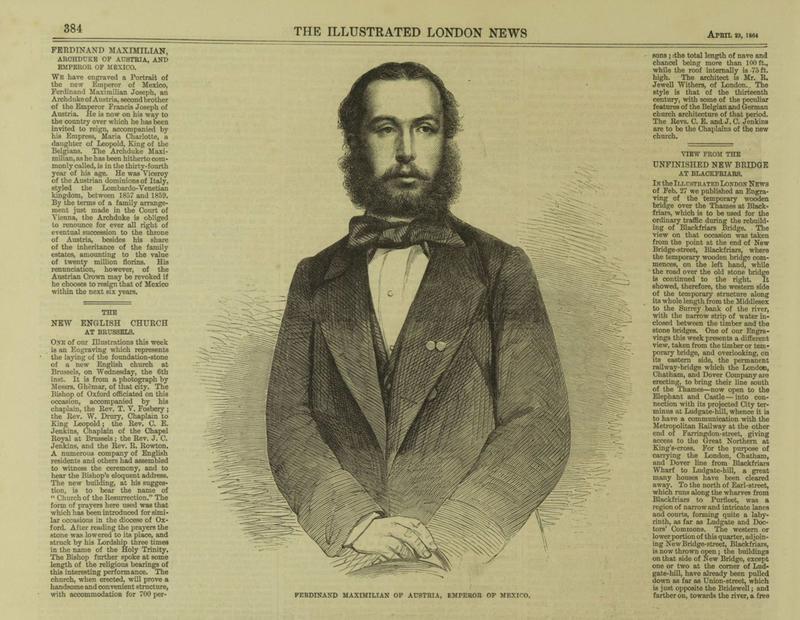

In the 1860s, the French Emperor Napoleon III’s invasion of Mexico, and creation of a new imperial state under the aegis of the Austrian Archduke Maximilian—whose eventual execution by a Mexican firing squad Manet’s famous painting imagined for posterity—precipitated heated arguments in Britain about the duties of European civilization and the future of global order. From the 1870s and 1880s, as Latin American politics began to appear less endemically unstable, reflections on what had underlain the transition from disorder to something approaching solidity began to appear much more widely in mainstream public debates about empire and Home Rule, and in studies of the ‘science of politics’. There were few major issues in nineteenth-century British political and social argument in relation to which Latin America was not, at one time or another, found to be relevant.

In terms of substance, then, there is plenty to gain by injecting the subject of Latin America back into the study of Victorian political thought and intellectual life. But the topic also encourages broader conceptual and methodological reflections. In particular, it helps to illuminate the patterns of international connection and exchange which lay behind Victorian arguments about foreign politics. Most students of the period realise, if only in the back of their minds, that most controversies about foreign politics in nineteenth-century Britain had counterparts overseas. If pressed, they might acknowledge also that these debates must often have rested on precisely the same texts and sources of information, especially in Western Europe and the United States. Thinking more systematically about these circulations, and about the relations between the responses they inspired in different national contexts, may help move us towards a form of comparative and connected intellectual history which can do justice to an increasingly (albeit inconsistently) integrated nineteenth-century world.

'The Execution of Emperor Maximilian', (1868-9), by Édouard Manet, held at the Kunsthalle Mannheim.

Take, for instance, the debates over Francia’s Paraguay in the 1820s and 1830s. These rested, for a time, almost entirely on a single text, a personal and historical narrative by a pair of Swiss doctors. Published initially in French in 1826, it was rapidly translated (with slightly different titles) into a range of other European languages. Responses to the work in the contemporary public presses of Britain, the United States, France, Germany, Austria, Spain, and Italy discussed it in relation to different issues in their respective nations’ politics; but the fundamental philosophical dividing lines about the merits of Francia’s regime were strikingly similar across these very different states. These responses were all independent, but the international dynamic was usually more complex. In the case of public arguments about the French invasion of Mexico in the 1860s, for example, Mexican agents sought to manipulate European presses and business associations to declare for or against the Emperor Maximilian; French, British, Spanish, and American newspapers entered into spats with one another about the morality and legality of the operation; and texts produced by writers close to the architect of the scheme, the French Emperor Napoleon III, were pulled apart across Europe for hints about France’s ultimate ambitions. The point here is not only that much ‘British’ public political argument about Latin America was not, in its international contexts, terribly distinctive, but also that it was sometimes barely ‘British’ at all. In many cases, it reflected or simply replicated arguments made in other countries, under other pressures, for other purposes.

Maximilian, the Austrian Emperor of Mexico, in the Illustrated London News in 1864.

Latin America, then, has the potential to lever open new ways of understanding the international and transnational dynamics within Victorian intellectual history more broadly. Other case studies of political thought and debate on the internal politics of other regions might serve similar purposes. But the distinctive Anglo-European-North American circuits and exchanges which bore upon attitudes towards Latin America represent a particularly valuable starting point. For modern historians, surfeited with sources, the question of how to handle the international connections between political arguments is one which demands answers distinct from those proposed by students of the medieval and early modern eras. It is straightforward enough to examine how particular international influences impacted upon particular well-known writers and thinkers. The problem for historians of British thought who want to reach beyond the intellectual aristocracy is to find ways of holding British political and social arguments structurally in tension with ideas, theories, and patterns of representation generated and circulated overseas. There will be different solutions to this conundrum. A world in which the issue is taken more seriously, however, will be one in which historians have to think quite differently about the character of British exceptionalism, and about the processes by which it was constructed. The implications—for Victorianists, for modern British historians in general, and for other modernists as well—will be significant.

Alex Middleton is a College Lecturer in Modern British History at St Hugh’s College, Oxford.