The End of Enlightenment: A Conversation with Richard Whatmore

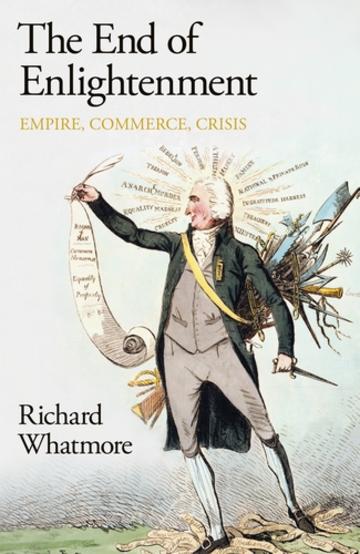

Published earlier this month, Richard Whatmore’s The End of Enlightenment (Penguin, 2023) is based on the Carlyle Lectures in the History of Political Thought which he delivered at the University of Oxford in 2019. Whatmore (St Andrews) spoke to Richard Bourke (Cambridge) to mark the publication of his new book.

Richard Bourke: This is an original, bold, and searching work which poses fundamental challenges to our understanding of the Enlightenment by forcing us to reconsider its culmination. It reflects critically on the common view that Enlightenment ideals were consummated, proposing instead that in the end they were sorely disappointed. Part of the originality of the work is historiographical in character. I see two particular strands of historical thought as underpinning your approach. One is a Pocockian understanding of “Enlightenments” as a diverse set of responses to the Wars of Religion and their aftermath. Enlightenment, from this perspective, is the triumph over superstition and enthusiasm. The other is a Hontian preoccupation with the jealousy of trade, where commerce appears as drawn into the dynamics of international conflict rather than ensuring that deadly rivalries will be resolved. But of course Pocock and Hont were not singing from the same hymn sheet in all respects. Synthesising their insights carries risk. How do you see these two accounts as presenting a coherent picture of the period and are they both, taken together, sufficient for unpacking its principal dynamics?

Richard Whatmore: What a great question to kick-off with. You are right about my acceptance of plural Pocockian enlightenments and the definition of Enlightenment as whatever strategy harnesses or limits superstition and enthusiasm. Neither can ever be vanquished in perpetuity, of course, and one of the points I want to emphasise is that the necessary vigilance made manifest in worrying about the recurrence of superstition and enthusiasm led to accusations that what itself was intended to maintain Enlightenment had turned fanatic. Early drafts of the book were read by Pocock and I think he agreed that Enlightenments amounted to differing strategies for preventing wars of religion. That means that there can be autocratic Enlightenments as well as Enlightenments fostering liberty, the latter being much more difficult to achieve.

Turning to the Hontian strand, jealousy of trade and worries about national debts and rich countries turning poor through competition all loom large in The End of Enlightenment. I think that both Hont and Pocock thought that when commerce became a reason of state, new kinds of chaos were let loose upon already turbulent politics. And commerce itself could become a source of fanaticism, which is one of the points regularly made in debates about luxury, as well you know. So the Enlightenment itself, if it was to continue in different contexts, had to prevent new forms of religious-style conflict from breaking out. Above all, it had to take on the challenge of preventing commerce from destroying states, communities and ranks, turning the world upside down in the same way that religious or republican revolution had done in times past.

What this means is that Pocock and Hont were far closer in their analyses of what was happening in the eighteenth century than might be presumed, something clear from the recent article ‘Liberalism and Republicanism’, written with Lasse Andersen, on Hont’s and Pocock’s papers. Pocock knew that his account of commercial humanism in The Machiavellian Moment was inadequate. He later said that Hont and Michael Sonenscher had developed his insights in ways he could never have imagined, but greatly appreciated. There are differences of focus. Like Pocock I am interested in free states and republics above others and the cultures necessary to sustaining liberty. Like Pocock, I don’t have much faith in jurisprudence or law, especially in times of crisis. But like Hont, I’m interested in fanatic forms of liberty turned nationalistic and xenophobic, unmooring themselves from defences of modern civilisation.

J. G. A. Pocock (1924-2023)

Richard Bourke: One of the most important consequences of the book, it seems to me, is the fact that it refocuses attention away from specific doctrines that we might associate with the Enlightenment – or, indeed, with various Enlightenments – and towards problems and their solution. For me at least, this implies criticism of earlier accounts which selected thinkers on the basis of their religious and ideological commitments. For instance, this approach can be found in Peter Gay and Jonathan Israel. By comparison, you bring together a highly diverse set of figures confronting a common dilemma. In their different ways, they value Enlightenment but they fear its demise. If this is a fair depiction, what are the assorted “ends” of Enlightenment envisaged by your cast of characters?

Richard Whatmore: Again you’ve very neatly captured this author’s intentions. What is significant to me about the late eighteenth century especially, meaning the period after the Seven Years' War, is the extent to which so many political thinkers and actors saw themselves to have failed, to be living in times that had shifted, and where they had to adjust to new circumstances, often changing their beliefs in the process. Hence what I’m fascinated by is not a figure’s ideological or theological identity but the way that they applied their beliefs to real challenges, found themselves to have failed, and then readjusted. It is sometimes said that Turgot or Condorcet were advocates of ‘progress’, for example. But if Turgot thought it had never been achieved in practice, because of the nature of the French state, and Condorcet argued ultimately that human nature had to change, then I’m not sure that either of them thought progress to be possible in their time. The same goes for Godwin and Wollstonecraft, the latter being remarkable because she lived through the collapse of republican virtue and equality, embodied by her relationship with Gilbert Imlay, while attempting repeatedly to pick up the pieces, finding new solutions. Some, like Paine, said that reform or the creation of free republics is impossible because of a cancer in the system, Britain, and ended up arguing for perpetual peace by means of the transition mechanism of global war.

Regarding Jonathan Israel, I think that free states were in crisis in the eighteenth century to the point of becoming endangered species, so projecting democratic futures from the United States or France and after does not capture what contemporaries were thinking, doing or worrying about. But I have much more sympathy with Peter Gay. For a time, I was entirely perplexed by his association of the Enlightenment with ‘the party of humanity’. But then I realised, partly through the papers of post-war intellectual historians we’ve collected at the St Andrews Institute, that what Gay was trying to do was to work out what could be salvaged from European history after World Wars and the Holocaust, and whether there were antidotes to fanaticism in the eighteenth century. So Gay, with his ongoing interest in preventing superstitions and enthusiasms from turning violent, was much closer to the approach I’ve adopted. Back to Jonathan Israel. I don’t like ‘Democratic Enlightenment’ for the reasons given, and I think everyone was ‘radical’ because they all thought that what existed would not last; the point was to adapt to change. Strategies to prevent wars of religion from breaking out afresh were contested, but I think that the strategies themselves were the Enlightenment in action, and that is what we ought to be studying. Now something very positive about Jonathan Israel: a publisher once said to be me they could only publish a book of mine (not The End of Enlightenment), which would not sell many copies, because it was effectively being subsidised by Israel’s books, the sales of which were always enormous. This is worth bearing in mind.

A short answer to the question of ‘ends’. The general end is preventing fanaticism but it takes different forms. I think everyone hated the outbreak of war and civil violence and the establishment of rapacious and plundering imperial endeavours (Smith’s mercantile system), but they were divided about the means of preventing fanaticism, especially on the issue of whether republican communities fostered liberty or fanaticism.

Richard Bourke: The book concentrates on French and British figures. I take this to be indicative rather than exhaustive. For example, Kant is mentioned in the final chapter of the book. Since the most explicit debate about the prospects for Enlightenment took place in Prussia in the 1780s, I wonder what the case of Germany might add to your overarching thesis?

Richard Whatmore: I think that Hont and Sonenscher, and most recently Béla Kapossy, Avi Lifschitz and many other scholars, are right in describing Europe’s monarchies as the locus of some of the most imaginative and innovative reform strategies of the century. In part of The End of Enlightenment I refer to Hume’s optimism about civilized monarchies. It proved to be brief. I have always thought that the relationship between small and large states is key to understanding the eighteenth century. Scotland after the Union proves a model for the incorporation of a smaller and poorer state into a larger empire. The process was watched closely, as Franz Fillafer has recognised, across the Holy Roman Empire and beyond. But the reason I’m less interested in Germany is because I think the most remarkable change in the world was the rise of free commercial states like Britain and the Dutch Republic. The latter fell, as everyone expected. Britain ought to have fallen too, allowing the advanced reform strategies of the French to restore a natural political order. Somehow, for the first time in history, a free commercial state proved better at fighting wars than any other form of state. This shattered France and the resulting perception of living in a disordered world makes French political thought singularly rich. By the time of the French Revolution, Burke was justifying the British subsidising the autocracies of Europe to better battle the French disease. James Mackintosh, however Burkean his apology for Vindiciae Gallicae, could never forgive such a stance. So the story of the German, Russian and Austro-Hungarian response to the rise of a highly peculiar free state like Britain is significant. But I’m not the person to do such work.

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804)

Richard Bourke: A pivotal part is played in the book by the recrudescence of “enthusiasm” after 1789. Is there a danger here of equating political with religious fanaticism, thus in effect establishing a continuum between the sectarian conflicts of the seventeenth century and the upheavals of the 1790s, or do you want to argue that, whatever the differences, there are essential continuities?

Richard Whatmore: I think that so many Whigs from the late 1770s and through the 1780s believed that they were living through the 1630s and were about to arrive at 1642. This was certainly the view of Shelburne, Price and their ilk, for whom George III was likely to become the worst of the ‘Stuarts’. And Hume too thought that justifying murder on the grounds of religious enthusiasm was akin to justifying it by enthusiasm for liberty. That liberty could easily turn fanatic and obsessed contemporaries is one of the central themes of The End of Enlightenment. Many contemporaries called the French Revolution a secular war of religion. Everybody knows this, but I think it is interesting to see the French republican fraternities establish themselves and then divide, having found true liberty, and then split further. I call the process the Protestantisation of France. The bottom line is that creating a republic has a great deal in common with the creation of an evangelical church.

Richard Bourke: How categorically did the Enlightenment end? After all, crucial accomplishments survived the mayhem of the late eighteenth century – like the authority of rational criticism, the regulation of church-state relations, the ideal of accountable government, the achievement of economic growth. Was the “end” that you highlight not just as much transitional as it was terminal?

Richard Whatmore: The gargantuan shock that accompanies the end of the eighteenth century/early nineteenth century is that Britain survives as a free state. It survives mainly because it is so good at war. Thoughts of abolishing empire are soon forgotten. A remarkable transformation occurs as Britain becomes a model free state for the following generation. This is depressing for former republicans who had far higher aspirations, people like Germaine de Staël, Benjamin Constant and Simonde de Sismondi (many others could be mentioned). The positive element is that Britain is a free state. But it also remains for many a mercantile system. I think that once this is recognised, the nineteenth century looks different and so does Romanticism. It means that everyone is living ‘after Enlightenment’, however powerful the strategies that still exist for making free polities tolerant and peaceful (at least domestically).

Richard Bourke: The book ends with a constructive vision of the vocation of history in which the past is viewed as a potential source of instruction rather than an object of blanket condemnation. I think of this as a defence of the discipline against pervasive moralism in research. Is this a fair assessment of your underlying approach?

Richard Whatmore: I’m running out of words, so the short answer is yes, that is a very good way of putting it. I think that if you study ideas in action, and the way they fail or succeed, you can learn a lot. And you tend not to moralise because there are never easy solutions to problems. Indeed, one of the things you cannot help but be struck by in the era of the end of Enlightenment is the passion with which people like Wollstonecraft stick to their principles, while being fully aware that they have failed to make them real, that their personal reputation is in tatters, and that they are ever more alone in their crusading quest. Wollstonecraft was most interested in the transition mechanism to equality. It was not enough to posit the vision. A dull sentence to finish: we don’t spend enough time on transition mechanisms from one reality to another, although they obsessed our ancestors.

Richard Bourke is Professor of the History of Political Thought and Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge. Richard Whatmore is Professor of Modern History at the University of St Andrews.