Rituals of Consent or Procedures of Decision-Making? Assemblies of Estates in Early Modern Europe

Assemblies of estates have usually been considered as standing at the basis of modern parliamentarism. Exactly because of that supposed continuity, historians have usually concentrated on (what they presume to be) “actual politics”, and they have conceived of these assemblies as legislative bodies of decision-making. My thesis is that this narrative of continuity is misleading. Early modern assemblies of estates should not primarily be described as procedures of decision-making but rather as symbolic-ritual performances: rituals of identity and consensus.

By “ritual”, I am referring to a repetitive, formally standardized, staged, performative, symbolic sequence of collective acts. Rituals are performative in that they bring about what they represent and usually commit the participants to what they enact. They are symbolic in that they refer to something beyond the individual act: they evoke a larger context of order, which they symbolize and simultaneously reinforce. Because rituals are performed in specific, repeatable, solemn forms, they place the individual act within a larger context and connect it with the past and the future. In this way rituals yield structure and continuity – and they do so in a way that transcends the change of individual agents and their intentions.

Opening of the English Parliament in Westminster during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, 1584. Engraving by Renold Elstrack, c. 1600.

By “procedure”, I mean a sequence of collective acts that are formally standardized as well (usually in writing). The procedure aims at producing collectively binding decisions. The precondition is that the participants submit themselves to the outcome of the procedure in advance, regardless of whether they like it or not. In contrast to rituals, decision-making is contingent here; that is, one could always decide otherwise. No one can know in advance whether a decision will be the “right” one. The key point is that this contingency makes collective decision-making risky. Open decisions don’t come without costs, they easily cause social tension and need justification. A decision is often divisive in social terms. Where there may have been a vague consensus before, an open decision makes dissent visible. This is why, from a historical point of view, explicit decision-making is by no means the rule, as we tend to think, but rather the exception.

Assemblies of estates – as a theoretical construct or ‘ideal type’ in the vein of Max Weber – were a common feature of pre-modern European monarchies. Beyond the considerable individual differences, they characterized a common political culture. Contemporaries themselves seem to have realized the common features as well; at least, they used the very same iconic patterns to depict these assemblies.

Political “estates” existed in almost every early modern European monarchy or principality. The rulers summoned the intermediate powers of each province because they required recognition, support, and, most of all, money. The noble vassals, church dignitaries, representatives of cities, and so forth used the situation of the ruler being dependent on their support to have certain liberties and privileges guaranteed to them collectively in written form. To defend these collective rights in the future they characteristically consolidated themselves into corporate bodies of estates. The rulers had an interest in making the assemblies’ collective decisions binding upon the country as a whole and all of its subjects (which was by no means undisputed). When this succeeded, the participants of the assembly merged into a unity capable of acting collectively.

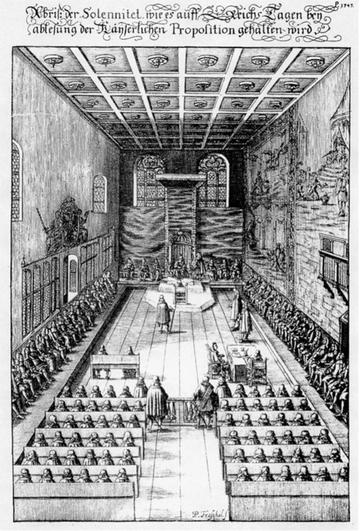

Opening Session of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire in Regensburg, 1654.

Despite all the differences, one can observe a general procedural and symbolic grammar of these assemblies. They evolved from occasional feudal court diets; that is, as personal assemblies of the vassals and the highest councilors at the ruler’s court. My thesis is that most of them basically retained crucial elements of this courtly character as long as they were summoned at all (the English House of Commons being a significant exception in many respects). The estates were convened ad hoc on special occasions. Thus, these were events (diets, days, Tage) rather than permanent institutions. As long as assemblies of estates existed, they were staged as monarchical invitations. The entire symbolic framing was that of an audience. Only the ruler could legitimately summon them; the estates had no right to assemble themselves spontaneously. Usually, a new ruler’s first assembly of estates was accompanied by splendid courtly spectacles, banquets, dancing, hunting, tournaments et cetera: events that served both the staging of the social-political community as well as the ostentatious self-presentation of the individual participants.

Generally, an assembly of estates differed from a ruler’s council in that the ruler could not simply invite whom he wanted, but there was an established circle of participants which could be more or less fixed in a register. The boundaries were fluid, though, and often a subject of dispute. As long as the law was shaped by precedence and tradition, the factual and uncontested appearance of a noble or city mayor at the assembly could determine to which territory they belonged. In many respects the social-political status and rank of a noble (with corresponding rights and obligations) depended on his factual participation in the assembly of estates, also because these were the occasions on which new members were ceremoniously admitted into their respective corporate bodies by means of the ritual of swearing-in.

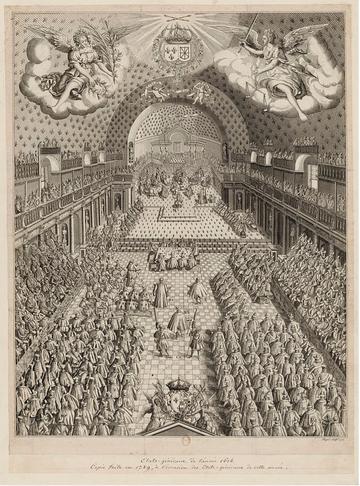

Opening session French Estates General, in the Hôtel du Petit-Bourbon in Paris 1614.

The participants were of extremely varied social status. On the one hand persons of high aristocratic rank had the right to participate as individuals, mostly as vassals of the ruler or church dignitaries. On the other hand, representatives of corporate bodies participated; that is, of cities, administrative districts, counties, ecclesiastical orders, universities, and so forth. The heterogeneous status of the participants was meticulously reflected and reinforced by their ceremonial treatment during the diets.

The opening ceremonies were probably the most formalized elements and had the greatest symbolic power (see also images 1, 2, and 3). The assembly always began with a church service, during which the assistance of the Holy Spirit was called upon and the entire event was provided with sacral legitimacy. Usually, a ceremonial procession through the streets took place as well, during which the estates accompanied the ruler to the church and then to the assembly place. In times of religious schism, the opening masses could become a central site for the symbolic staging of the confessional conflict.

Time and space of the assembly had to be marked symbolically in order for the event to be elevated demonstratively from the everyday life of the court. The variety of symbolic means ranged from cannon shots, bells, drums, and trumpets to armed militias, to symbols of presence such as royal insignia, heralds, coats of arms, swords, staves, scepter, baldachin, throne, and – if the ruler was absent – by his portrait. All possible objects, gestures, and choreographic arrangements could assume symbolic significance in this context, and literally anything could become the object of contention – up to the texture of the carpet or the decorations on the horses’ blankets. All of these signs served to define the event as a formal act of the entire political body and thus capable of making resolutions that were binding for the entire land – in contrast to just a spontaneous gathering.

Portrait of Emperor Francis I (1745).

The choreography of the participants during the solemn opening session of the assembly was of constitutive significance for the structure of the whole body politic. It was here that the central categories of the political and social order were staged and became manifest: by means of benches, steps, barriers, and the order of the seating. The spatial order was oriented towards the throne; the participants’ distance or proximity to the throne indicated their rank. The social barrier between the noble and communal participants was a barrier in the literal sense; the representatives of the cities and the rural districts were usually not even permitted a seat.

The plenary opening session was framed as the ruler’s request for the counsel and assistance of the estates for the benefit of the entire body politic. The ruler set the agenda in the form of a ceremonial proposition. As a rule, he did not recite it himself, but rather had his chancellor or another high officeholder speak on his behalf. The opening speeches were highly ceremonialized and left little leeway for surprise, let alone controversy. This was just as true for the answers of the estates, which were represented by their highest-ranking member. The estates presented their grievances and bade the ruler “most humbly” to remedy them. Both sides – ruler and the entirety of the estates – symbolically corroborated the welfare of the realm as the common basis of their actions and their desire to reach agreement. Mutual consensus and reciprocity, not dispute, was the ritual message.

Paradoxically, however, the solemn opening was also the public forum in which – already before any deliberations – conflicts could break out, the hierarchy of the estates could be contested, questions of status raised. For what was enacted here on the public stage would become a precedent, and legal claims could build on it in the future. But the ways to oppose what was publicly staged were very limited. There were basically two options for dissenters: they could either protest in solemn form, or they could leave the assembly. Mere presence would be taken as tacit consent. The reason why precedent was so dangerous was that there were no written statutes of procedure: the order rather arose from customary practice. In some cases, however, so much time passed between two assemblies that no one could remember the last one, and it was necessary to laboriously reconstruct from the archives how the ceremony had been held in the past. Whoever had an archive and historiographers at his disposal – usually the ruler – thus had a procedural advantage and could construe the tradition in his favour.

Seventeenth-century cabinet formerly containing the archives of the Dutch States General.

The actual deliberations began with the separation of the various corporations of estates into separate spaces (chambers, houses, Kammern et cetera). These bodies assembled in strict seclusion, often outside of the princely palace. This manner of proceeding was crucial, for it not only symbolized, but also generated, the boundaries and the independence of the different estates as separate corporate bodies. In these sessions the ruler himself did not take part. Usually, the participants were obliged to take an oath of secrecy. The secret of the deliberations was meant to secure the boundaries between the estates (which for the most part, however, was a fiction).

In general, each chamber had a common procedure of polling. All of the participants submitted their votes on the content of each point of the proposition in turn. They did so in hierarchical order, generally from the highest- to the lowest-ranking participant (although in some assemblies it was exactly the opposite). The head of the assembly had the final word and summarized the tenor of the votes. Usually, votes were cast as many times as necessary for a majority opinion to emerge. In this process, deliberation and decision were not separate but merged fluidly together. This was not a majority vote in the strict sense, which would presuppose that each vote had the same weight. Rather, the procedure had a symbolic character in that it simultaneously illustrated and reinforced the social position of the participants. The casting of the votes followed rank and was a sign of it. The role one took in the proceedings was thus hardly distinguishable from his role in the societal hierarchy.

However, there were important exceptions to this hierarchical procedure. Almost every assembly of estates established committees for special concerns in which representatives of the different chambers deliberated together. The most prominent exception is the procedure in the English House of Commons. Here, there was no seating order whatsoever: everyone simply sat down where there happened to be an available seat (except the representatives from London and York). Unlike almost everywhere else, the deliberations were clearly separated from the voting. During the debate each member was permitted to express his opinion on a matter once and only once. The voting then took place by acclamation, and if the speaker could not determine which group was in the majority, he had both groups counted. This procedure essentially meant that social differences of rank ought not to play any role and that each vote had the same weight. Not surprisingly, foreign observers saw nothing but disorder and confusion in this. In their eyes, the procedure was not at all in keeping with the gravity and prestige of such a glorious assembly. Actually, though, it was exactly this procedure that strengthened the House of Commons’ political homogeneity and capacity for action; it was the precondition for the unique political weight it attained from the end of the seventeenth century.

A meeting of the English House of Commons in the 17th century.

Communication between the different chambers was also strictly hierarchical and highly ceremonialized; it symbolized and strengthened the fundamental distinctions between the estates. There are ubiquitous examples of symbolic humiliation: the nobles would make the communal delegates wait outside the door, or kept them standing during the negotiations, or they would just ignore them altogether. The fundamental goal, however, was a unanimous resolution of the chambers (amicabilis compositio). Usually, complicated negotiation procedures would lead to a collective decision, which in the end would be presented to the ruler and accepted by him. In the end, the ruler’s requests were generally fulfilled. The estates could not simply refuse the ruler’s request without massively violating the conventions of due reverence. They could only, for their part, present “humble petitions” and hope to have their grievances settle in the future.

An assembly of estates generally ended as formally as it had begun, namely with a formal “conclusion” in the literal sense of the word and a ceremonial “leave-taking.” Just as the ruler had invited the estates, he also dismissed them. Without his formal permission, they were not supposed to leave. In fact, however, it sometimes happened that individual estates departed ahead of time in order to protest against the resolutions or even to reject them as binding. In cases of conflict therefore, the usual way was to leave or even circumvent the assembly entirely: either on the part of individual estates, who simply did not comply with the invitation, or on the part of the ruler, who just did not convene the assembly at all. As is well known, for various reasons many rulers were less and less in need of their estates’ support in the course of the seventeenth century. In some countries, the assemblies were replaced by standing committees. In other cases, they were summoned anyway. They must have had another function than just making decisions.

To return to my initial question: were the assemblies rituals of consensus or procedures of decision-making? As always with this kind of complex question, the answer is, of course, yes and no – it depends. On the one hand, assemblies of estates can be called procedures of decision-making. And they usually did pass resolutions in the end. On the other hand, much stood in the way of a clear and unambiguous decision-making process: the high value of social harmony and consent, the great weight of rank and honour, and, last but not least, the lack of power to force the minority to accept a decision which they did not agree with. Under these circumstances, compositio, agreement, was more appropriate than decisio, decision.

Unanimity, unanimitas, had a high spiritual value, since harmony was a sign of divine inspiration, while disharmony was considered the devil’s work (In scissura mentium deus non est). Unanimity was also desirable for pragmatic reasons, since dissent could hardly be articulated publicly, face to face, without personal loss of honour and the threat of an escalation into violence. In addition, the large weight of hierarchical rank clashed badly with the majority principle, since votes of different social weight could not simply be counted. The key point is that, as long as there was no monopoly on legitimate physical violence and no effective sanction mechanism against dissenters, it was difficult to deal with dissent.

A conflict over rank during the Imperial Diet in Regensburg, 1702.

This is why assemblies of estates were regularly staged as theaters of consensus and reciprocity. The customary negotiations and their symbolic framing hardly allowed for open contradiction. They offered very limited room for open-ended decision-making and made it difficult to settle conflicts between ruler and estates. At the same time, however, and paradoxically at first glance, it was precisely the assemblies of estates at which the great constitutional conflicts broke out – especially the harsh religious conflicts, which were simultaneously constitutional conflicts about the relationship between ruler and estates. Not surprisingly, the spectacular cases in which the diets became a scene of open conflict have been most intensively researched by historians: the German Reichstag of the Reformation period, the French États généraux during the wars of religion, the English parliament during the Civil War, and so on. But this is an optical illusion, as it were. Conflicts always attract more attention, if only because they produce much more documents. But conflicts between ruler and estates were the exception rather than the norm. So, there is just a seeming contradiction here: diets were a theater of consent and a site of dispute. Precisely because the forms of procedure provided very little room for settling open conflicts in a formal and legitimate way, they could quickly escalate and become uncontrollable once they had broken out.

Yet if the assemblies of estates fulfilled the function of decision-making only in a limited way, why did they take place at all? The answer is, because they were also significant social and political rituals. They represented or embodied the political whole in the sense that they made it sensually perceptible – visible, audible, tangible. In the ceremonial convening of ruler and estates, the entire political body, consisting of head and members, came into existence. As long as there was no written constitution of the modern kind, it was these ceremonial assemblies that ritually generated the political body as a whole and its fundamental internal structural principles anew over and over again. By attending the assembly, the participants accepted and reinforced the leading values and ordering principles of the body politic: namely, the estates-based structure as such, the hierarchy of the participants and their respective privileges, the principle of reciprocity and the ideal of consensus between ruler and estates, and, last but not least (and which is easily overlooked), the tacit exclusion of all the other subjects. Some of these principles were explicitly reassured each time, some of them were not fixed in writing at all but just ritually staged again and again. This made them appear self-evident, almost natural, beyond any need for justification, and therefore all the more effective.

It was not only the unity of the political body, but also its internal structure that these assemblies made manifest, they were the central arenas, the “theaters”, where status, rank and honor of each individual actor and the relationships between them became manifest. In this sense the assemblies served not least to maintain the privileged social status of the participants. This is why the estates were interested in them – even if there was not much left to be decided.

Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger, Rector of the Berlin Institute for Advanced Study.