Liberalism, Conservatism, and Reception History

In February, the Rothermere American Institute hosted a panel on ‘Liberalism, Conservatism, and Reception History’ with three leading scholars working in the field of ‘reception history’, generously conceived: Dr Claire Rydell Arcenas (University of Montana), Dr Glory Liu (Johns Hopkins), and Dr Emily Jones (University of Manchester). The session explored how writing the ‘reception histories’ of John Locke, Adam Smith, and Edmund Burke informed how each panellist thinks about (writing) the histories of liberalism and conservatism more broadly.

Together, the papers revealed when, how, and why Locke (1632-1704), Smith (1723-1790), and Burke (1729-1797) gained their current reputations as thinkers inextricably linked with certain (relatively narrow) political ideologies and traditions. In all cases, the three thinkers underwent dramatic transformations in the twentieth century: Locke became “liberal,” Burke became “conservative,” and Smith became “libertarian.” Generally understood as multifaceted, complex authorities in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Locke, Smith, and Burke were reinvented through processes that narrowed and constrained their influence in the twentieth, as each thinker was reinterpreted to align with (or made to represent) a seemingly consistent set of political goals and commitments. As a result, the earlier richness and messiness of their lives and legacies were obscured or forgotten.

The papers also explored a range of methodological issues connected to writing ‘reception history’ and the histories of various ‘isms’. For example, they emphasized the importance of considering non-traditional source bases, ranging from novels and cartoons to curriculum records and textbooks, when writing about the history of political ideologies. In addition, they called attention to the changing and malleable nature of categories like “Lockean,” “Burkean,” and “Smithian”—that what these categories signal is most often not an “authentic,” stable interpretation of what Locke, Burke, or Smith actually meant or intended, but rather the ideals of their readers being projected (or rather retrojected) onto the historical figure. Through this attention to sources, methods, and approaches, the panellists stressed that ‘myth-busting’—seeking simply to complicate or contextualise a thinker’s present-day public significance by refuting anachronistic interpretations—is insufficient. Instead, they argued that we also need to understand—through the study of history—when, how, and why ‘myths’ of the ‘liberal Locke’, ‘conservative Burke’, or ‘free-market Smith’ came to be.

In a paper exploring Locke’s relationship to liberalism and the Liberal Tradition in the United States, Dr Arcenas underscored how easy it is to forget entirely about liberalism or, for that matter, any “ism” when thinking historically about Locke’s influence in American intellectual life before about 1940. She traced how and why Locke became ‘liberal’ in the twentieth century and revealed that Locke was of a very different relevance to earlier generations of American men and women who knew the philosopher best for his penetrating insights into human understanding and his ability—as exemplar and model—to inculcate in Americans virtuous character development.

Locke’s American story, Arcenas argued, reveals the payoffs of interrogating rather than simply acknowledging or identifying moments of ‘invention’ or ‘becoming’ in liberalism’s history. Furthermore, she emphasized how researching and writing about Locke across three hundred years of American history clarified for her liberalism’s potential to serve not only as an object of inquiry and investigation but also as a heuristic tool—something that, precisely because it is an invented construct, we can use to better understand the past. Such work, she explained, entails simultaneously “letting go of” liberalism—freeing oneself from the bonds of categories, concerns, and priorities of the recent past to investigate a deeper past—and “holding on to” liberalism as a point of reference and comparison to make sense of what separates but also unites past and present.

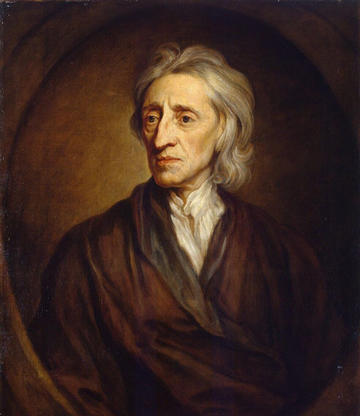

John Locke (1632-1704).

In the second paper, Dr Jones reflected on her experience of writing the afterlives of both Edmund Burke and Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881), and how these historical figures were transformed into respective ‘founders’ of a modern conservative tradition at the turn of the twentieth century. Burke, an Irishman and Whig politician, was generally chastised after his death in 1797 as an inconsistent madman who split his party over the French Revolution. Disraeli, meanwhile, was widely criticised during his lifetime for his supposed opportunism, slipperiness, and lack of principle—often rooted in ideas of orientalism and antisemitism. Thus, later recoverers of Burke had to explain not only how a Whig could become a Conservative (and so aligned with Toryism) and from there be seen as relevant to modern politics, but also address Burke’s Irishness, ‘madness’, and inconsistency so that he could instead be widely understood to be a significant, consistent political thinker.

With Disraeli, critical recovery not only focused on reimagining the ways in which Disraeli’s politics ‘spoke’ to modern political issues and legitimated particular policy proposals but also encompassed the reinterpretation of his Jewishness and the extraction and canonisation of his novels–especially Sybil (1845)–as significant historical, literary, and political texts. Through this process, Burke and Disraeli were mythologised as respective ‘founders’ of complementary but distinct ‘strands’ of conservatism, which could be used together, or picked up and put down according to the demands of both intellectual and political national and international climates.

Hence, Jones highlighted three main points regarding what she has ‘learnt’ about conservatism. First, the fundamentally relational and historically contingent nature of the traditions she has studied, and thus the insufficiency of ‘vertical’ accounts of either ‘ideologies’ or political movements. Second, the importance of broader, cross and non- or less explicitly partisan contexts and sources in shaping ideas about, in this case, conservatism–including, for example, Liberal debates over Irish Home Rule, which invoked Burke or influential ‘pessimistic’ socio-economic histories which drew inspiration from Disraeli’s Sybil. Finally, Jones stressed the overarching significance of historical reconstruction as a fundamental means of cementing individual and group political and intellectual identities for much of the two centuries that her work has covered, and the seeming decline of this capacity in recent decades.

Dr. Liu’s paper drew on a theory of canonisation from Stefan Collini’s seminal 1991 work Public Moralists: Political Thought and Intellectual Life in Britain to both highlight some of the features of Adam Smith’s American reception as well as to challenge the very idea of a generalisable, linear “model” of canonisation. In the eighteenth century, Americans engaged with Smith’s two published works, The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), as “living resources”. They sought an enlightened approach to practical morality, the development of critical moral faculties, statesmanship and political economy, and used these works as vital but by no means exclusive resources. But treating Smith as a resource stood in great contrast to what was to come–that is, the creation of discipleship and authority around Smith’s name and ideas.

In the early nineteenth century, the development of political economy as a science–rather than a branch of politics–led academic and popular writers alike to define themselves as either following or departing from Smith’s ideas. Ongoing debates about free trade politicized these positions further; by the last quarter of the nineteenth century, Smith’s authority was fully established as little more than a totem or symbol of one’s partisan position on trade. In the mid-twentieth century, in the wake of the Great Depression, Smith’s authority was reinvented again as the father of the Chicago School’s approach to positive economics and unique brand of free-market advocacy. The Chicago version of Smith eventually became so powerful and recognisable that most people (outside of Smith scholars) assume it to be the version of Smith.

Liu’s telling of Smith’s American reception underscores what she has called the “politics of political economy”: that ideas about the economy and economic life–even and especially those from Smith–need to be understood as products of their time. But they are also languages of authority used to make claims on how political and economic life ought to be arranged. Hence, Smith’s canonisation is not politically neutral, nor is his significance confined to purely scholarly matters as Collini suggests. The most recent wave of revisionist Smith scholarship, Liu argued, shows how amidst contemporary anxieties about the stability of modern liberalism, Smith is used to articulate both its deficits as well as alternative possibilities. Yet rather than cynically attributing this to scholarly trends, Liu suggests that we ought to continue to examine the present more critically, through the eyes of reception: that the proliferation of so-called “Smithian liberalisms” tell us something more about our demands and the limits of the language of liberalism, rather than something about Smith himself.

During the Q&A that followed, audience members and the panellists engaged in a robust conversation on several historical and methodological themes that emerged over the course of the session. Audience questions invited panellists to reflect on how and why they all arrived at their projects at roughly the same moment in time—in the early 2010s; the opportunities and challenges that arise from pursuing projects with such broad chronological scopes; and whether there are certain moments in history when the public is more or less receptive to complex renderings of and engagement with thinkers and their work. The evening concluded with a reception that allowed further conversation with undergraduate and graduate students.

Dr Claire Rydell Arcenas is Associate Professor of History at the University of Montana. Her first book, America's Philosopher: John Locke in American Intellectual Life (Chicago, 2022), received the 2023 István Hont Book Prize. She is currently writing a book about the Declaration of Independence, American Democracy, and Civic Education in the United States, 1776-2026. At Oxford, she is a Fellow-in-Residence at the Rothermere American Institute and a Plumer Visiting Fellow at St Anne’s College.

Dr Emily Jones is Lecturer in Modern History at the University of Manchester. She is the author of Edmund Burke and the Invention of Modern Conservatism, 1830-1914: An Intellectual History (OUP, 2017), which won the 2018 Longmans-History Today Prize and was a Financial Times ‘Book of the Year’. She is currently completing a monograph provisionally titled One Nation: The Disraeli Myth and the Making of a Conservative Tradition.

Dr Glory Liu is the Assistant Director for the Center for Economy and Society and Assistant Research Professor at the SNF Agora Institute at Johns Hopkins. Her first book, Adam Smith’s America: How a Scottish Philosopher became an Icon of American Capitalism (Princeton, 2022), was named a Top 5 Biographies of Economists by the Wall Street Journal and received the 2024 Best Monograph Award from the European Society for the History of Economic Thought.