The State and Intellectual History: The Hartlib Circle and the Forgotten Reform of English Education, 1649–53

It is uncontroversial to suggest that gunpowder is more interesting than committee minutes, a scientist more obviously relevant to scientific history than a venial clerk. And so, it is the case that a network of scientists, mathematicians, and scholars such as the Hartlib Circle of the mid-seventeenth century, overtly pursuing schemes and projects—including the production of saltpetre—to transform learning have attracted some of the finest works of the finest minds of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Members associated with the group ranging from John Dury to John Milton proposed breath-taking schemes to transform England’s educational landscape, from its curriculum to accessibility of schooling. As the fresh treatment of the issue by Howard Hotson in his excellent new work on post-Ramist thought shows, the Hartlib Circle and the intriguing figure of the great intelligencer himself, Samuel Hartlib (1600–1662), continues to entrance and enthral.

Front Cover of Howard Hotson's The Reformation of Common Learning: Post-Ramist Method and the Reception of the New Philosophy, 1618-1670 (Oxford, 2021)

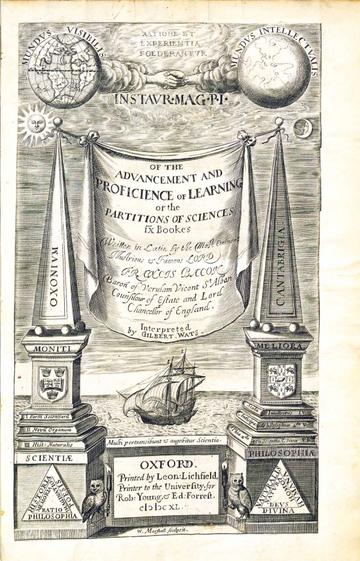

Yet, there remains an unread verso to this well-thumbed page. Hartlib and his allies were not statesmen. Throughout the period of the English Revolution, they attempted to persuade various regimes to change the nature of pedagogy in England by implementing schemes inspired by the likes of Francis Bacon and Jan Amos Comenius. It is easy to forget that in this role the Hartlib Circle were petitioners to the authority of the time. Change, if it were to arrive, would be delivered by the various parliamentary and protectorate regimes of the 1640s and 1650s. That change did not come is well known to historians of education in the period. But why? There is a disinclination to consider seriously what the English government at the time wanted to do with England’s learning. As a result, the MPs and bureaucratic officials devoted to the administration of education—such as the Committee for Regulating the Universities—have been as visible historiographically as leaves in winter.

Title Page of Francis Bacon's Advancement and Proficience of Learning (Oxford, 1640)

In contrast, my doctoral thesis takes seriously the attitude and thought of the English state regarding education in a period not short of climacterics. While it is easy to be seduced by the attractive proposals of pioneers outside of government, the approach and importance of those in authority should not be dismissed, nor should a lack of innovation be conflated with dull inaction. The English Parliament during the mid-seventeenth century was a government rooted in post-Reformation monarchical attitudes to education: namely, that the primary purpose of education was to instil religious and obedient uniformity with the state in a supervisory role. Alongside this general principle was a concurrent focus on producing an educated clergy who would offer a different type of education by sermonizing and catechizing throughout the nation. The universities had always been seen as the fountains of the ministry, and in an age when the profession of schoolmasters was nascent at best and heavily dependent on the ministry, the ties between education and the church were very tight.

For the Interregnum governments, educational policy was to a great degree dominated by the religious context in the tumultuous period following the collapse of the Stuart regime. The governments were concerned with ensuring the nation’s children were raised in obedience and piety. As Oliver Cromwell, between convivial feasting and bucolic games of bowls, said to the scholars of Oxford in May 1649, “noe Com[m]onwealth would flourish without learninge” and the Parliament “meant to” promote it. This aim required good teachers, clergymen, and the bureaucracy to police them. It also required a clear sense of what was pious, which was, in turn, dependent on whatever role a religious settlement envisioned for the clergy. Parliament, therefore, approached questions of education with a pre-existing mindset and in that mentality educational reform intersected with church settlement. The Hartlib Circle’s various schemes to reform English education met with disappointment not because Parliament was uninterested but because they were dedicated to a different approach.

Portrait of Oliver Cromwell by Samuel Cooper 1656

The Hartlib Circle, therefore, can be interpreted as a warning, a reminder to remember the importance of the governing authority in intellectual history. Parliament’s attitude to education is often treated as a blunt, conservative reaction typical of those in power: lumbering, conforming statesmen unwilling to accept the ingenious proposals from minds plugged not into Westminster but into intellectual networks. But this is only partly true. What was as much a problem as the distractions of rule, or a tendentious attitude, was that Parliament was wedded to a very different approach to education. This influenced its actions and made the fate of education frequently dependent on contextual developments in, and debates over, the English Church. The 60 or so free schools established in Wales by the English government between 1650–3 were founded by commissioners for the propagation of the gospel—a group primarily attempting to settle problems with the provision and quality of preaching—not by disciples of pansophia.

Engraving of Parliament during the Commonwealth 1650

The idea of promoting the gospel throughout the kingdom was crucial to the English Commonwealth (1649–53). Since schoolmasters were often considered in the same bracket as ministers, and because education was necessary for the propagation of the gospel, it was entirely natural that an attempt to solve a dearth of godly ministers in Wales should also lead to parliamentary commissioners intervening in Welsh pedagogy. Ultimately, intellectual historians must not equate conservatism with narrow mindedness, nor forget the all-important role of the state as an agent of intellectual development, even if it initiated a gradual change, rather than an explosive break.

Alex Beeton is reading for a DPhil in Early Modern History at New College, Oxford.

Follow us on Twitter @OxfordCIH