The Encyclopédie Nouvelle: The 19th Century’s Magnificent Achievement and Glorious Failure

In his 1745 prospectus to the Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Denis Diderot celebrated the progress of the arts, sciences, and crafts. The general enlightenment conspicuous in French society, he observed, stemmed from the important work of dictionaries, of which the Encyclopédie he and Jean le Rond d’Alembert edited was the most significant and ambitious. By distilling all the discoveries and questions of the sciences, arts, and crafts in the form of a dictionary, they contributed significantly to the development and compass of knowledge. Dictionaries enabled disciplines and practices to complement each other. The Encyclopédie played, according to Diderot, the critical role in building the interconnectedness and accumulation of knowledge. The eight volumes and six hundred illustrations that comprised the Encyclopédie were, as Diderot made clear, the consequence of the great historical chain of all the sciences, arts, and crafts.

Diderot’s confidence in the Encyclopédie’s decisive role in advancing humanity to perfection set the tone for the Enlightenment. Immanuel Kant’s 1784 essay, An Answer to the Question: ‘What Is Enlightenment?’, encapsulated this attitude and the ensuing duty: ‘Enlightenment is man’s emergence for his self-incurred immaturity’, an immaturity that stemmed not from knowledge itself but from humanity’s ‘lack of resolution and courage’ to use that knowledge. Ten years later, and five years after resolution and courage mobilised the French in the storming of the Bastille, Condorcet declared in his Esquisse d’un tableau historique des progrès de l’esprit humain: ‘nature has set no term to the perfection of human faculties; that the perfectibility of man is truly indefinite; and that the progress of this perfectibility, from now onwards independent of any power that might wish to halt it, has no other limit than the duration of the globe upon which nature has cast us.’

These words reverberated into the next century. They resounded in Henri Saint-Simon’s 1810 Esquisse d’une nouvelle encyclopédie, ou introduction à la philosophie du dix-neuvième siècle, which acclaimed knowledge’s role in human perfection and celebrated Diderot’s role in illuminating humanity to that task. Saint-Simon observed that Diderot and d’Alembert’s extraordinary genius, like Bacon’s and Leibniz’s before and Condorcet’s after, made the history of what was, and had to be, learned to free humanity from its fetters. But Saint-Simon believed Diderot and d’Alembert had failed to achieve their stated goal. The new intellectual, cultural, social, and political order stemming from their work broke decisively with the Old Regime, but it failed to achieve the unity of thought that was also fundamental to human emancipation. The Enlightenment had been revolutionary, but it had not been emancipatory. Saint-Simon believed it was his destiny to rethink the eighteenth-century Encyclopédie for a new century. His Esquisse d’une nouvelle encyclopédie sketched the plan for an encyclopaedia that would unify all forms of knowledge and yield a new form of social organisation whose unificatory force was absolute and emancipatory power boundless. He proclaimed: ‘la philosophie du XVIIIe siècle a été critique et révolutionnaire, celle du XIXe sera inventive et organisatrice’ (‘the philosophy of the 18th century was critical and revolutionary, that of the 19th will be inventive and organisational’). For the remaining fifteen years of his life, he, and his amanuenses – first the historian Augustin Thierry, then the mathematician and founder of sociology Auguste Comte, and finally the mathematician Olinde Rodrigue – dedicated their energies to achieving that goal. They failed, but their task was later undertaken by others.

Henri Saint-Simon (1760-1825)

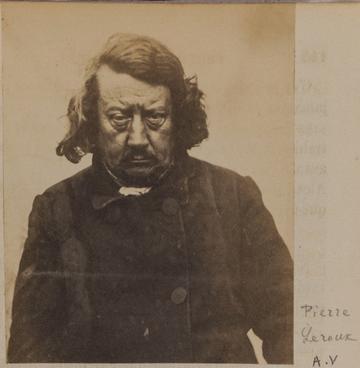

Inventive and organisational: this was the goal set by Pierre Leroux (1797-1871) and Jean Reynaud (1806-1863) for their own eight-volume Encyclopédie Nouvelle: dictionnaire philosophique, scientifique, littéraire, et industriel (1834-1848), a monumental work that, in Leroux’s words, embraced ‘by means of a general doctrine … the entire spectrum of human knowledge’. In combining the critical and revolutionary in Diderot and d’Alembert’s eight-volume Encyclopédie with the inventive and organisational in Saint-Simon’s Sketch, they sought to fulfil both Diderot’s and Saint-Simon’s aims. This made it a work of scope and ambition that surpassed Marc Antoine Jullien’s Revue Encyclopédique (1819-35), to which they were enthusiastic contributors, and all other established nineteenth-century encyclopaediae, such as Eustache-Marie Courtin’s Encyclopédie moderne, or Ange de Saint-Priest’s Encyclopédie du dix-neuvième siècle.

Leroux and Reynaud marshalled an impressive team of leading French, English, Polish, Russian, German, and Italian scientists, economists, philosophers, historians, and women and men of letters. The assembled contributors included the famous authors Georges Sand and Charles Augustin Saint-Beuve, the geologist, mining engineer and social investigator Frédéric Le Play, the historian Edgar Quinet, the philosopher Charles Renouvier, the feminist thinker Pauline Roland, and the scientist Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire. The Encyclopédie Nouvelle’s publisher was none other than Victor Hugo’s and Honoré Balzac’s: Charles Gosselin.

As one of France’s leading editors, whose other notable authors included Walter Scott, Alfred de Vigny, Alphonse de Lamartine, and Alexis de Tocqueville, Gosselin was captivated by Leroux’s and Reynaud’s Encyclopédie, and it is easy to see why. Reynaud and Leroux were remarkable individuals with formidable reputations and winning personalities. Reynaud was a top graduate of the famous École Polytechnique. He was an impressive scientist and philosopher with a penetrating mind and highly organised and systematic way of thinking. Leroux, by contrast, was a printer by trade and entirely self-taught. He was original and quick-thinking; his ability to generate ideas with speed and originality held those around him in awe. He was seen by many as the Rousseau of the nineteenth century. He had co-founded, with the academic and journalist Paul Dubois, what became France’s most important and influential newspaper of the first decades of the nineteenth century, Le Globe. Marx called Leroux a ‘genius’, and it is little wonder he did. The Encyclopédie Nouvelle challenged fundamentally and at the outset the Hegelian encyclopaedia whose ontological structure announced a totalising knowledge and the end of history. Instead, the Encyclopédie Nouvelle incorporated an important change in philosophy – one that in many ways reflected what Marx would later call for in his 1840s critiques of Hegel and the Left Hegelians. It advanced a total yet not totalising or closed understanding of knowledge and reason. Rather, it was attentive to feeling, sentiment, nature, and faith. These were explored in ways that Leroux and Reynaud believed could lead to new forms of social solidarity and an inclusive humanity.

Pierre Leroux (1797-1871)

The Encyclopédie Nouvelle’s scope was vast, mirroring the comprehensive science it set out to promote, and its entries were original in both extent and intent. The topics stretched from the letter ‘A’, ‘the vowel that occupies the first place in the alphabet of nearly every nation on earth’, to the dense fifty-page entry ‘Zoroastre’. Expressions of the fundamental philosophical change that Marx would call for appeared in articles on ‘conscience’ (consciousness), ‘sommeil’ (sleep) – a complex piece that, unlike any other encyclopaedia article of this time, focused on dreams – and a book-length entry on ‘eclectisme’. They were also central to two sprawling articles, ‘économie politique’ and ‘Adam Smith’, and all the other related articles on political economy, written by Jules Leroux (1805-1883), Pierre’s younger brother.

The extent to which the Encyclopédie Nouvelle’s ambition to achieve new forms of social solidarity and a genuinely inclusive humanity is, along with Jules Leroux’s articles on political economy, perhaps reflected best in the entries on Eastern religions: Leroux’s entries on Brahmanism, Buddhism and Orientalism, alongside Reynaud’s on Zoroaster. These essays fundamentally challenged established opinion on Orientalism. The entry Orientaliste, written by Leroux, defied the much-vaunted view of the Orient, as generalised by Benjamin Constant and confirmed by Hegel and Victor Cousin, the leading philosopher of the July Monarchy. They characterised the Orient as backward-looking, excluded from History’s march of progress, arrested in time. Instead, Leroux insisted that the Orient was characterised by a profound and ‘entirely modern’ erudition whose results were, in Leroux’s words, ‘so many conquests for philosophy’, and whose ‘progress is linked to the very history of the progress of modern philosophy.’ While Hegel and Cousin saw the Orient as the modest starting point of the intellect’s course of development, with the West achieving its self-conscious and triumphant conclusion, Leroux sided with Friedrich Wilhelm Schlegel and judged the Orient to be ‘the first source of all ideas and spiritual development.’ In short, Leroux argued, with Schlegel, that ‘the whole of higher human culture lies indisputably in the Orient.’

In emphasising feeling, sentiment, nature, and faith alongside reason, understanding, and consciousness, Leroux and Reynaud sought to expand the scope of what knowledge meant. Thereby they paved the way to new and inclusive forms of social harmony, something Leroux developed fully in his De l’humanité, de son principe et de son avenir (1840). Though Leroux and Reynaud had, from the outset, important ideological and philosophical differences – differences that stemmed from two contrasting visions of socialism, one hierarchical (Reynaud’s), the other egalitarian (Leroux’s) – they understood how these differences worked through a series of internal articulations as a common thread of the entire theoretical fabric of the Encyclopédie Nouvelle. This strength proved a weakness too. And though Leroux and Reynaud completed the eight volumes they had designed for their Encyclopédie, whole sections remained incomplete. While this attempt to unite ‘the entire spectrum of human knowledge’ failed, the Encyclopédie Nouvelle achieved a notable success. It transformed nineteenth-century understandings of knowledge, achieving ‘the mutual encouragement’ of the disciplines promised in Diderot’s 1745 Prospectus at the same time as suggesting new and inclusive forms of social organisation, as outlined in Saint-Simon’s Esquisse. That the Encyclopédie Nouvelle remained unfinished detracts in no way from its singular intellectual and political achievement: a revolution of thought and a reorganisation of knowledge aimed at bringing about an inclusive humanity.

Michael Drolet is Senior Research Fellow in the History of Political Thought, Worcester College, and Visiting Researcher at the Maison Française d’Oxford.