The Estates General and the King of France: The Imperfect Union

The king of France, though an absolute monarch, was no tyrant, but a judge and mediator, his power limited not only by the fundamental laws of the kingdom, but also by representative assemblies and courts of justice. He received petitions and grievances, sent them to be considered by his council and, if he found them reasonable, he put appropriate measures in train. In this way, from the Middle Ages, the king governed ‘through his great council’. These assemblies might be representative of the whole kingdom (e.g. the Estates General), of one of the orders of society (e.g. assemblies of the clergy), or of a single province or pays (e.g. the provincial estates). Here, we are mainly concerned with the Estates General – the best known of these assemblies.

The Estates General brought together delegates elected from each of the three ‘orders’ of French society: the clergy, the nobility and the third estate (which incorporated representatives of the countryside as well as of the towns). Their duty was to allow the sovereign to exercise power, but also to oversee that he did so in a just way. The Estates General were an occasional institution: they were called by the king just eight times between 1484 and 1614, after which they were not called again until 1789.

The Estates General of 1561, from Le Portraict de l'assemblée des estatz, tenuz en la ville d'Orleans, au mois de Janvier, mil cinq cens soixante, unknown artist, 1570.

The Estates General were first convoked by King Philip the Fair in 1302, yet the term was not used until the end of the fifteenth century (before then, the word used was just ‘estates’). Their primary function was to ratify the taxes that were to be given to the king – this was, in fact, why the estates were originally instituted. Indeed, when King Philip brought together the first assemblies in the fourteenth century, it was to demand additional resources because those gathered from the royal demesne were no longer sufficient.

Also, the Estates General were a means for the king’s subjects to make their voices heard. The Estates representatives wrote and submitted petitions, remonstrances, and grievances, which were transmitted in so-called cahiers (‘quires’) from 1484 onwards. The role of the institution was purely consultative, however. What is more, representatives who were deputised to the Estates General were limited by an imperative mandate: they were bound by the contents of the cahiers and by the instructions that accompanied them. Their power, in other words, was limited.

The Estates General were called by royal mandate. The nobility was represented by noble fief-holders, peasants were assumed to be represented by their lords, while representatives of the third estate consisted of royal officials, members of town councils, lawyers and notaries, doctors of medicine, and occasionally merchants. The delegations of the clergy consisted of archbishops and bishops, abbots, a large number of canons (chanoines), and a few priests.

Each bailiwick (bailliage) or ‘shire’ (sénéchaussée) was supposed to be represented by three deputies, one for each of the three orders of society. Each order chose their representative by a voice vote, by simple majority. Once these representatives of the Estates came together, the separate cahiers de doléances were bound together in one volume each per order. The associated debates could be initiated either by the king or by these Estates deputies. After the plenary opening session, which was presided over by the king, each order would meet separately – a change of practice which was introduced in 1560. Three cahiers were presented to the king in the formal ceremony closing the assembly. Deputies were only permitted to leave with the permission of the king.

At the end of each session, the cahiers were considered by the royal council. The king could, if he thought fit, use them as the basis for an ordonnance or an edict, but he was under no obligation to do so. King Henri III, who planned to reform a kingdom which was universally regarded as in crisis, promulgated a great ordonnance in 1579, the so-called Ordonnance of Blois, which was intended to restore the principal tasks and responsibilities of the Estates representatives (as demonstrated in the study by Mark Greengrass).

Each meeting of the Estates General took on its own particular character, according to its specific circumstances. In the sixteenth century, the Estates General were always held in the context of a crisis, either because of the Wars of Religion between Catholics and Protestants and/or because of periods of weak royal power, all the while the sovereign seeking the support of his subjects to overcome these problems. In response to requests for subsidies, the assemblies always responded with a categorical refusal. They regarded the Crown’s poor financial state as the result of extravagant expenditure and mismanagement of its revenues.

King Henri III at the Estates General in Blois, 1577, from Carmen de tristibus Galliae, Bibliothéque Municipale, Lyon, ms. 0156, f. 33v.

With the Crown in difficulty, the Estates General of 1588 attempted to increase their own institutional power. A majority of the deputies belonged to the ultra-Catholic League party. They forced the king to bind himself by oath to the Edict of Union, which established Catholicism as the only religion of king and kingdom, and to declare that the Edict was henceforth a fundamental law of the kingdom. Another demand contained in the Edict was that a decision taken unanimously by the three orders should become a fundamental and unrepealable law (which was not a new idea, incidentally, as it had already appeared in some form in 1560 and 1561). It was clearly formulated by the three orders in 1576 and 1577, repeated by the third estate in 1588 and proposed once more by the clergy to the other two orders in 1614. This reform also entailed that the assembly meet every five to ten years. The deputies of 1588 further demanded a right to review the consideration of their cahiers by the king’s council, and proposed that twelve deputies from each estate should be allowed to sit on this council.

Believing his authority to be in danger, on 23 December 1588 King Henry III determined to have the Duke de Guise, the head of the ultra-Catholic League, executed. Several deputies from the third estate were also arrested, as was the Count de Brissac, the presiding representative of the nobility. This was unprecedented. And so, the iron fist of the Estates was brought to an end by the majestic stroke of Henri III.

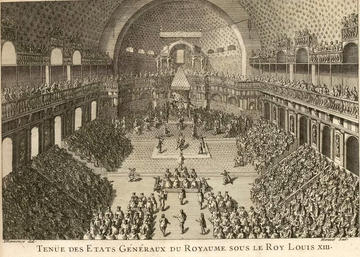

Estates General of 1614, from an engraving by Hérisset, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, 1728.

As Arlette Jouanna has written, ‘in formulating their demands, the Estates general above all regarded themselves as the incarnation of the king’s body – in other words, a collective expression of sovereignty’. They were the limbs of a body politic whose head was the king. They also relied on the old Latin adage quod omnes tangit, ab omnibus approbari debet – what touches all should be approved by all. This principle of a legislative function for a representative assembly was revived in the eighteenth century. But at that time, it was based on new ideas which fundamentally altered what it meant. In June of 1789, the Estates declared themselves to be unassailable. (And then a new, national Assembly took its place and appropriated royal sovereignty for its own means.)

The 1593 assembly of the Estates General is the least well-known. This was the only time the Estates were not summoned by the king, but by the head of the League, the Duke de Mayenne, who from 1589 planned to hold a meeting to legitimise the new institutions established by the ultra-Catholics. The Estates General were seen as the only way to find a solution to the major political crisis in which the kingdom of France had been engulfed since Henri III had died without leaving a direct heir. His heir according to Salic Law was Henri IV, yet he was a Protestant, not a Catholic. The assembly was opened on 26 January 1593 at the Louvre. Its aim was to elect a new king. And it ended in confusion following the abjuration of Protestantism by Henri IV.

The journal of Guillaume de Taix, canon of Troyes, reporting on the proceedings of the Estates in 1577, shows that the deputies were well aware that the issue was one of sovereignty. This assembly posed questions such as whether collective disorder would be overcome if sovereignty were exercised collectively, or whether it was possible for an assembly to fall into the hands of a radical minority. The deputies of the first estate meeting held at Blois (1576-7) regarded the risks of a powerful crown to be outweighed by those of an unlimited assembly. Such attitudes prevented an evolution along the lines of the English parliament or the Polish diets – examples which were explicitly referred to by the third estate in 1588.

The English parliament, in fact, brought together the functions of the Estates general and those of the Parlement of Paris, the premier court of justice of the kingdom, which was composed purely of magistrates. This combination was what gave it its ability to withstand the English monarch. What all these institutions had in common was that they were founded in custom, rather than in some formal act of creation.

Historians have been concerned with two avenues of research: the social composition of the assemblies (in the work of Neithard Bulst and Manfred Orlea), and the study of the contents of the cahiers de doléances, a rich source of information on economic, religious, and political history. The problem in studying the Estates General is that most of the key texts remain unpublished, including the cahiers and the formal minutes of the assemblies. Much, therefore, remains to be done. Another rich field of study which deserves more attention is the political thought on the role of the Estates General, as articulated by jurists such as Guy Coquille and Jean Bodin. One would very likely discover that their writings are soaked in an admiration for ancient Rome…

Sylvie Daubresse, CNRS, Centre Roland Mousnier, Sorbonne Université.