Intellectual History and the Problem of Incest

In the earliest stage of my doctoral research, I was interested in exploring traditional concepts of early modern intellectual history such as ‘liberty’ and ‘right.’ It was probably not a bad way to start, but back then this seemed like the only approach. As time proceeded, I was liberated from my preoccupation with those grand concepts, finding other exciting ways to work on the history of ideas. The crucial moment for me was when I came upon the mid-seventeenth-century English controversy over the definition of incest. Although it may seem like a peculiar subject, the problem of incest opened rich avenues for exploring important questions of religion, law, and obligation.

The idea of incest is worth the consideration of intellectual historians in general, because there is in fact no universally agreed definition of incest—and this in turn raises the question of who determines it. While many people in our times might think that the basis of the prohibition of incest is the high probability of negative genetic effects, this approach is a twentieth-century one. Moreover, since science alone does not determine morality anyway, the definitions of incest in many countries and regions are still influenced by non-scientific authorities. Among them, religious ones play important roles in determining incest, or prohibited degrees (i.e. the list of people whom one is prohibited to marry). Especially in Abrahamic religions, it was religious institutions which defined marital ethics on the basis of their understanding of their scriptures. In short, the definition of incest is far from self-evident and has a long history of intellectual contestation.

Frontispiece to the King James' Bible, 1611.

Given that religious authorities were central in defining incest, mid-seventeenth-century England offers a particularly interesting case. In the wake of the English Civil War, the overarching system of national church and ecclesiastical courts was abolished, and the civil power introduced an alternative set of marital ethics. With regard to the definition of incest, the parliament radically reduced the number of prohibited degrees from thirty to eleven, without a clear justification [Figures 1 and 2]. This new definition of incest troubled those who were familiar with the previous rules, which had been authorized by the former Church of England. However, since the old decrees had been outlined under different intellectual assumptions almost a century ago, they could not simply reassert these antiquated rationales, especially as they now lacked the institutional support of an established church. In these circumstances when the authorities peculiar to England seemed uncertain, some Anglican theologians started to consider the kind of rules that might oblige all human beings, rather than the English people specifically.

Figure 1: The thirty prohibited degrees in Parker’s Table (EGO is proscribed from marrying all those in the yellow shapes).

Figure 2: The eleven prohibited degrees under the 1650 Adultery Act.

In the context of urgently seeking a guide to universal human obligation, the ideas of universal divine positive law and natural law loomed large. On the one hand, universal divine positive law refers to a divine command by which God—as an external lawgiver—intended to bind all mankind. On the other hand, natural law is the internal moral instruction that is innate to all human beings. Discussions of these ideas were not new at all, but crucially in this period, some writers started to inquire more explicitly why certain laws in historical texts were still obliging and to what extent they could be binding. This development is central to the writings of two Anglican theologians, Henry Hammond (1605–1660) and Thomas Barlow (1609–1691), on the definition of incest.

Hammond was a staunch defender of the traditional Anglican order, and so insisted upon the thirty prohibited degrees. There, the main challenge for him was that the thirty degrees were originally derived from Leviticus 18. By the 1650s it was quite difficult to uphold the contemporary validity of the Old Testament commands in the wake of new historical scholarship of Scripture. Except for some particularly enthusiastic millenarians, few scholars thought that Mosaic law could be directly applied to contemporary England. Hammond tried to overcome this difficulty by suggesting that Leviticus 18 was in fact universal divine positive law. He argued that the prohibitions in Leviticus 18 were given to Adam and Noah despite the lack of such a record in Scripture. For Hammond, the fact that the fathers of all mankind had received these commands meant that contemporary English people were also obliged to follow them.

Portrait of the English churchman Henry Hammond, D.D., by Sylvester Harding in the British Museum, London.

While Hammond’s position did save his fellow Anglicans from losing their conventional morality, it implied that all human beings were obliged to the thirty prohibited degrees, which were, to be fair, rather extensive. Thomas Barlow, one of Hammond’s contemporaries, spotted this implication and pointed out how ‘irrational’ Hammond was in imposing such an extensive obligation on all mankind. Barlow criticized Hammond’s argument for universal human obligation by divine positive law. Instead, he endorsed the Catholic theologian Francisco Suárez’s exposition of law. Suárez had stated that the obligation of law arises only when the lawgiver’s intention is sufficiently promulgated for those who are under it. On this basis, Barlow found it very difficult to accept Hammond’s argument that Leviticus 18 was a divine positive law obliging all mankind, when there was no reliable evidence that the lawgiver God had intended to bind all human beings with these commands. Moreover, even if Scripture had declared that the Levitical degrees were universal human obligation, Hammond’s view was still problematic because there were ‘poore Americans in West Indies’ and pagans who had no access to Scripture.

The Plague of Thebes: Oedipus and Antigone (1842), Charles Jalabert

Barlow’s alternative was a minimal set of prohibited degrees by natural law, to which all rational human beings were bound. Closely following Hugo Grotius’s account of natural law and the minimal prohibited degrees under it, Barlow suggested that only marriage between the people in the direct lineage (primarily parent and child, but also grandparent, grandchildren, etc.) should be universally proscribed. Even here Barlow did not fail to acknowledge that the obligation of natural law did not extend to mentally challenged people. Clearly, Barlow’s suggestion was by no means designed to preserve pre-Civil War Anglican morality. For him, it was more important to clarify the limit of any alleged universal human obligation than to give a sense of security to a particular religious group.

Painting of Thomas Barlow (1608/99–1691) by an unknown artist, c. 1672–5 in the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

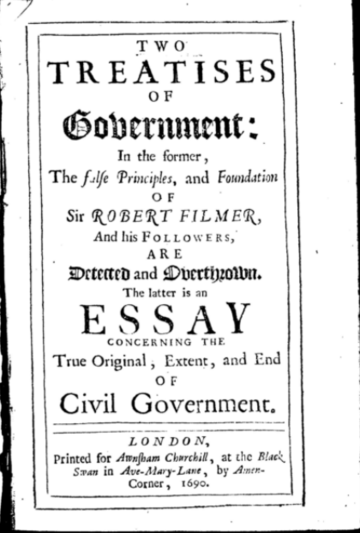

While this discussion of universal human obligation was triggered by the particular circumstances of the Civil War, the effort to determine the extent of obligation continued after the Restoration. As for the definition of incest specifically, it does not seem to have provoked much debate immediately after the Restoration. Parker’s Table was re-instituted without much dispute (we can still find it on the last page of the modern Book of Common Prayer). After experiencing the collapse of old certainties, however, divines and scholars realized that many aspects of conventional moral and ecclesiastical codes in fact fell short of addressing contemporary human obligation. The limit of natural law obligation also came to be mentioned more explicitly than before, as most famously presented in John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1689). The rise of moral theology in Restoration England can in part be explained as an endeavour to rethink the relationship between the conventional sources of morality and actual human obligation.

The Title Page of the First Edition of John Locke's Two Treatises of Government.

Though the definition of incest was no longer a problem after 1660 in the same way it had been before, it nevertheless provides us with a window into the way that the Interregnum divines grappled with the questions of morality, Scripture, and human obligation. I would not have been able to see this interesting contact point, where theology, political thought, and practical human concerns came together, had I insisted on narrowly digging into ideas of ‘liberty’ or ‘right.’ The idea of incest has a history as rich as those grand concepts. Studied in the light of mid-seventeenth-century England's deep crisis of authority, the debates that surrounded the concept of incest have the potential to reveal some fundamental shifts in intellectual history.

Hannah Dongsun Lee is reading for a DPhil in Early Modern History at St. Edmund Hall, Oxford.