The Reception of Confucianism in Early Modern Britain

The reception of Confucian philosophy in early modern Britain provides an interesting case study of the ways in which global philosophies and religions newly encountered by early modern Europeans were accommodated by, and also interrogated through, the lenses of Europe’s own intellectual preoccupations. In the case of the British reception of Confucianism, we can see how Chinese philosophy added a new, Chinese battleground for the fighting of local confessional and polemical disputes, most notably questions of natural reason and materialism.

The first mention of Confucius in an English text is most likely in Richard Hakluyt’s famous travel compendium of 1598/9-1600, Principall Navigations. However, it was not until the late‑seventeenth century that Confucius became a name more widely familiar to British readers. This was chiefly the result of the proliferation of Jesuit texts about China, most notably the publication in Paris of the 1687 Confucius Sinarum Philosophus, a translation of three key Confucian texts including The Analects (論語, Lunyu).

Confucius Sinarum Philosophus (1687)

The Jesuit interpretation of Confucius as a natural moral philosopher seems to have at first been fairly widely accepted within orthodox Anglican circles. Indeed, its most common use seems to have been as a weapon of critique against the supposedly amoral materialism of Hobbesian philosophy. The first English translation of a Confucian text, uncovered by Matthew Jenkinson, was Nathaniel Vincent’s little known 1685 partial translation of the Great Learning (大學, Daxue), taken from the Jesuit Prospero Intorcetta’s Sapientia Sinica of 1662, a very rare work published in China itself. Vincent’s translation fully reproduced Intorcetta’s narrative of a virtuous Confucianism compatible with Christianity, translating the first line of the Great Learning (大學之道,在明明德) thus: ‘The intent of great Men in Knowledge and Instruction, does consist in the enlightening of our Spiritual Power conveyed to us from Heaven, by the virtues.’ Vincent’s use of the word ‘Heaven’ (天, tian), which does not appear in the original Chinese, follows the Jesuit interpretation of Confucianism in which heaven is a deistic entity comparable to the Christian God, and thus reproduces their vision of Confucianism as a form of natural theology. Most interestingly, Vincent’s translation of the Great Learning was appended to a sermon he had given in 1674 as Charles II’s royal chaplain. The sermon focused on the dangers of Hobbism, decrying the ‘Leviathan-philosophy’ which sees honour as merely being based on ‘Power alone’. For Vincent, Confucian philosophy was a rebuttal of this Hobbist political cynicism, and he even refers to China within the sermon itself by drawing on ‘the Religion and Learning’ of ‘an old Pagan Empire on the further side of Asia’ governed by ‘the Son of Heaven’ (天子, tianzi), to show that a proper, non-Hobbesian understanding of honour can be deduced from natural reason.

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679)

The first documented English language response to Confucius Sinarum Philosophus follows a similar anti-Hobbist line. In a letter by Christopher Cratford, undated but established by William Poole to have been from 1687, just months after the first publication of the Sinarum Philosophus in Paris, Cratford discusses his readings of the work. Just like Vincent, he contrasts the ‘extreame’ philosophy of Hobbes with the ‘more modest’ writings of Confucius and follows the Jesuits in his interpretation of Confucius as a philosopher focused on using ‘right reason’ to prove the importance of ‘universal charity’ and to ‘decerne good from evil.’ In this way, the initial reception of Confucianism in England seems to have followed the Jesuit interpretation of Confucian natural theology, seeing virtuous Confucius as being opposed to the cynical Hobbes.

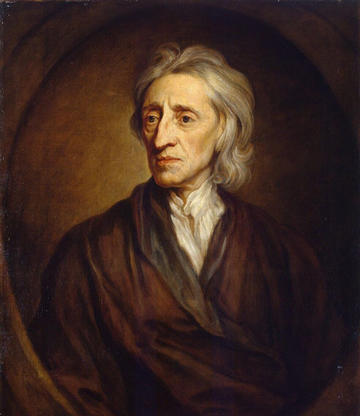

However, the Jesuit interpretation of Confucianism as natural theology was receiving increasingly vigorous attacks in the late‑seventeenth century as the Chinese Rites controversy began to deepen, a dispute which was partly concerned with whether Chinese reverence for Confucius should be regarded as religious worship. John Locke was closely following this debate: although his reading notes on China have been surprisingly rarely used in scholarship on early English sinology, they reveal a keen interest in the rites dispute. Most of Locke’s notes came from staunchly anti-accommodationist interventions in the controversy, particularly the Dominican China missionary Domingo Navarrette’s work and the 1700 compilation Historia Cultus Sinensium. These works led Locke to write in his notes that ‘the [Chinese] Literati have noe other Deity but the material heaven.’ Locke is quite clear what this materialism means for the idea of Confucian natural theology, drawing on neo-Confucian metaphysics to show that the ‘literati admit noe true spirits’ and believe that after death souls become ‘a part of that matter which they call Li [理, pattern] or Taikie [太極, taiji, the supreme ultimate].’ There is no doubt in Locke’s mind, therefore, that Confucianism is utterly opposed to Christianity, both in terms of devotional practices and in the issue of a matter-spirit distinction, and indeed, the vast majority of his notes on Confucius himself focus chiefly on the worship Confucius receives in his temples. For Locke, therefore, Confucius represents an atheistic idol rather than a figure of virtue. The attitude displayed in his notes filtered through into his published work, most notably in the posthumously published 1706 fifth edition of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding, where Locke added a passage claiming that ‘the Literati, or Learned, keeping to the old Religion of China [Confucianism]…are all of them Atheist.’

John Locke (1632-1704)

This hostile interpretation of Confucianism as materialistic, and therefore atheistic, was then made use of by Europeans who saw in neo-Confucian metaphysics a tool which could be used for their own ends. Locke’s close friend, Anthony Collins, followed Locke in his interpretation of Confucianism as a materialist ideology, writing in one of his responses to Samuel Clarke in 1711 that, just like ‘Ancient atheists’ such as ‘Strato and Xenophanes’, as well as modern ones like Spinoza, the philosophy of ‘the sect called the Literati in China’ also claims that ‘there is no other substance in the universe but matter.’ But, instead of sharing Locke’s hostility, Collins followed Pierre Bayle in using materialist Confucianism as evidence that it was possible to believe in a materialistic philosophy and still be virtuous. In his 1727 published commentary on John Rogers’ sermons, Collins approvingly quoted Leibniz’s argument that the Chinese ‘certainly…surpass us…in practical philosophy, that is, in the precepts of ethics and politics adapted to the present life and use of mortals’, and even copied Leibniz’s claim that China ought to send missionaries to Europe to teach Europeans the ‘use and practice of natural religion.’ Confucianism’s supposed marriage of materialist philosophy and moral virtue fitted with Collins’ wider aim, often categorised as “Deistic”, of defending a materialistic view of emergent properties in matter. Regardless of labels, Collins’ materialistic metaphysics was certainly regarded by many as deeply heterodox. His appeal to Confucian philosophy was thus an inversion of the previous arguments: Confucius could be both virtuous and a Hobbesian materialist.

By the mid-eighteenth century, this interpretation of Confucius as both materialistic and moral became seemingly more mainstream, albeit with what might be termed a more “Epicurean” focus on luxury and the senses. In Oliver Goldsmith’s epistolary novel, A Citizen of the World (1762), a Chinese philosopher is presented as arguing that rather than being motivated by reason, our pursuit of knowledge is instead motivated by ‘sensual happiness’ and thus since ‘the senses ever point out the way’, luxury is a useful motivating power for improvement in society. This is then rounded out with an invented quotation from Confucius: ‘that we should enjoy as many of the luxuries of life as are consistent with our own safety; and the prosperity of others, and that he who finds out a new pleasure is one of the most useful members of society.’ An article in the Critical Review was quick to raise the spectre of Hobbism, accusing ‘this Chinese philosopher’ of being akin to the ‘Philosopher of Malmesbury [i.e. Hobbes].’ But the same reviewer nevertheless went on to praise the Chinese philosopher’s ‘excellent remarks upon men, manners, and things.’ This seems to mark the quiet acceptance of Confucianism as a philosophy not necessarily in agreement with mainstream British religious and philosophical thought, but nevertheless deserving of respect. In less than a century, Confucius the austere spiritual theist had been turned quietly into an Epicurean, materialist atheist — the very thing he had initially been invoked to combat.

Ross Moncrieff is a DPhil candidate in history and examination fellow at All Souls college, Oxford. His research focuses on early modern British understandings of China.