Thomas Hobbes and the Rejection of 'Objective Being'

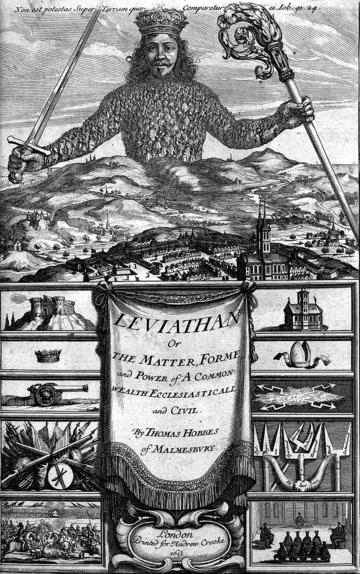

On the lower right side of the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651), we can find a little noted, yet important, detail. Here, on the two prongs of a fork symbolizing the spurious distinctions used by scholastic philosophers and clergymen to ensnare people at large, are inscribed the words “real” and “intentional”. Given the historical use of those terms, we may safely assume that both are meant to qualify “being”. What this detail thus indicates seems to be Hobbes’s wholesale rejection of any distinction between “real” and “intentional being” as the mere invention of ill-willed scholastics. Indeed, next to said fork is another on whose prongs we read “temporal” and “spiritual”, a distinction claimed by Leviathan to have been forged “to make men see double”.

While the rejection of the distinction between real and intentional, or (as we shall see) objective being, is part and parcel of Hobbes’s well-known rebuttal of scholastic philosophy, tracing its origins yields some interesting results. Firstly, it reveals that Hobbes’s engagement with scholastic categories did indeed play an important role in his intellectual development, despite his explicit statements to the contrary. Secondly, the reconstruction of how Hobbes initially sought to dispel any notion of a dual nature of being casts serious doubt on both the view that his epistemology is inherently skeptical and that his materialism is a gratuitous assumption with no philosophical backing. Seeing the development of Hobbes’s theoretical philosophy within the context of the still-dominant late-scholastic thought of his time may, therefore, shed some light on the theses that he ultimately were to maintain.

Hobbes, Leviathan frontispiece, British Museum.

The notion of “intentional being” (esse intentionale) dates back to at least Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) and his attempt at clarifying Aristotle’s views on cognition. According to Aquinas, the human soul receives the “form” of an exterior object in order to sense it. While this form determines the being of the object, say the form of a horse that determines this flesh and these bones as a horse, once received by the soul it no longer alters its being, but makes it sense the object from which it derives. To account for this specific alteration, Aquinas claimed that the received form must have another “mode of being” (modus essendi) in the soul than it did in the exterior object. It was to that end that he introduced the term of “intentional being” (esse intentionale).

Now, Aquinas did not have a concept of “objective being”. It is, however, important to note that the Franciscan John Duns Scotus (c. 1265-1308) equated the two in his Ordinatio. Whereas an accident inhering in a substance can be said to possess “formal being” (esse formale), in that this form determines the being of said substance, once that form is received by the human soul it does not alter its being. Sensing a stone, the soul does not become stone-like. Rather, it sees the stone by receiving its form as endowed with “objective being”, or, as Duns Scotus also called it, “representative”, “diminished” or “intentional being”. Thus, Scotus not only allowed for a distinction of being, but moreover conceived of objective being as something less than formal being. Only “representational”, it seems to have no reality outside a soul to which it represents an exterior object. It is only a “being objected” to the soul so as to render cognition possible.

John Duns Scotus, Studiolo di Federico da Montefeltro.

The distinction between formal and objective being was, although with alterations, inherited by the Jesuit philosopher Francisco Suárez (1548-1617) and, seemingly through him, René Descartes (1596-1650) who used it to argue for the existence of God in the third of his Meditations. As is well known, Hobbes was invited to formulate a series of objections to that same work. What is perhaps less known, is the fact that Hobbes also engaged with Descartes’s philosophy in what it usually called his “Second Optical Treatise”. Here, Hobbes engages with Descartes’s theory of vision and scolds it on several counts. Most importantly, he rejects the Cartesian notion that it is the soul that sees, when the body to which the soul is somehow attached is mechanically affected by an exterior object. Hobbes is thus adamant that “vision [is] formally and really (…) nothing besides motion (visio formaliter et realiter nihil aliud sit praeter motum)”. This in turn entails that “what formally, and strictly speaking, sees is nothing besides that which is moved, that is, a particular body”. Given Hobbes’s later attacks on “scholastic jargon”, his use of the evidently scholastic terms “formaliter” and “realiter” to explain his own views on sensation is rather surprising. Yet Hobbes does not merely reuse an old vocabulary, he subjects it to a serious revision from within the conceptual structures that these terms were originally meant to express. Whereas Descartes had allowed for a tripartite distinction of the concept of “reality” (realitas) into “objective”, “formal” and “eminent”, Hobbes deflates the concept of reality to that of formal reality by equating “formal” with “real” being, given grammatical expression by the coordinating conjunction “et”. Formal being thus exhaust the category of what is, and no room is left any notion of “objective” or “diminished being”.

Crucially, this conceptual operation entails the rejection of a view of cognition in terms of “internal ideas”, that is, the notion that we sense only those ideas or representations that are somehow “in our mind”. While this view is not really Descartes’s either, Hobbes’s also denies that what we see is in fact only an internal idea. Indeed, these representations are not “the things seen, or the object of vision, but the act of vision itself (ipse actus visionis).” Had this been the case, we would have needed another set of “spiritual eyes”, somehow lodged inside our soul, able to perceive these equally internal ideas. Yet this is not, contrary to a longstanding historiographical tradition that insists on the contrary, Hobbes’s view. As he explicitly states: “the appearing thing is the object itself (res apparens est ipsum obiectum)”. What we have epistemic access to is not merely our internal ideas. Rather, those ideas are the very acts through which an exterior object appears as exactly that, that is, as an exterior object. And indeed, as Hobbes was to affirm some 14 years later in De Corpore, “[t]he object is that which is sensed: thus, we say more accurately that we see the sun than light (…) light and color (…) are not objects, but phantasms of the sentient beings.” On both Hobbes’s early and mature view, then, we do not primarily sense an internal phantasm. We sense the exterior cause that initially produced it.

Rene Descartes, Image Attribution: G. Edenlinck.

While his explicit use of scholastic terminology could be ascribed only to Hobbes’s engagement with the categories that Descartes had himself inherited, he does, albeit shortly, point to a wider context of intellectual interlocutors in his critique of Thomas White’s De Mundo, presumably written a few years after the second optical treatise. Here, he criticizes “many of those who philosophize” (plerique philosophantium) for calling our ideas “things insofar as they are in the mind” (res prout sunt in animo) rather than merely “image of the thing” (imago rei). It is not entirely clear to which philosophers Hobbes is referring, but expressions to the effect of “things in the soul” abound in scholastic theories of cognition, from Henry of Ghent, Duns Scotus, and Petrus Aureolus to Hobbes’s fellow novatore Descartes who might not be a scholastic in any straightforward sense, yet still borrowed heavily from that tradition. What such philosophers have in common, then, is to wrongly claim that an idea is a thing in the soul. Seeing that an idea in merely an act of a body, and not a body itself, it has no spatial extension and consequently could not be objected to a subsequent act of sensation through which cognition should take place. What Hobbes thus rejects is the notion that our soul should somehow contain ideas endowed with a reality distinct from the exterior objects to which they stand in an intentional, and that is, on Hobbes’s telling, a causal relationship with. As Hobbes would say during his discussion with Bishop Bramhall: “in all senses the Object is the Agent”. We do not see our ideas as internal objects of our acts of sensation. Rather those ideas simply are acts through which their causal origin appears.

On this hastily sketched view of Hobbes’s engagement with theories of cognition drawing on scholastic conceptual structures, what emerges is the view that he neither confined our knowledge of the world to internal representations, nor assumed that those representations have no necessary relation to exterior reality. Seeing Hobbes as a thinker more seriously engaged with scholastic thought than is usually assumed should thus make us reconsider the pertinence of some of those labels with which his theoretical philosophy is often described. Should we insist on using such labels, and I am unconvinced that we should, Hobbes instead emerges much more of a “realist” than anything else.

Esben Korsgaard Rasmussen has a Ph.D. in the history of philosophy from the University of Copenhagen and is currently a Carlsberg Junior Research Fellow at Linacre College, Oxford.