Ukraine: Between West and Different Easts

‘Ukraine between East and West’ is one of the most common metaphors of Ukrainian historiography. It has been regarded as a stable metaphor, one that is simultaneously productive, open and topical. The ‘West’ in this formula is rather static and obvious—it is ‘Western Europe’ which begins in Poland and whose manifestations in Ukraine are the Magdeburg Law, the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, as well as the Uniate (Greek-Catholic) Church, seen as a synthesis of Western and Eastern Christianity that has managed to survive despite all the efforts of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union to destroy it.

Ukrania quae et Terra Cosaccorum cum vicinis Walachiae, Moldoviae, Johann Baptiste Homann (Nuremberg, 1720)

The ‘East’ in this binary formula can mean a variety of things: the Byzantine Empire, Eurasian nomads, Russia, the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire (sometimes defined all together as the ‘Turkic-Islamic world’).

As for Byzantium, historians mostly agree with Ivan L. Rudnytsky’s argument that ‘Ukraine, located between the worlds of Greek Byzantine and Western cultures, and a legitimate member of both, attempted, in the course of its history, to unite both traditions in a living synthesis’. If the ‘East’ was understood as the world of the nomadic non-Christian peoples of the Middle Ages and/or the Turkic-Islamic world of the early Modern Age, the connective ‘between’ was usually transformed into a political tool: on the one hand, asserting Ukraine`s underestimated achievements in defending Europe and, on the other, explaining the alleged ‘backwardness’ of its historical development.

Crimean Tatar squadron of the Russian Empire (1920).

In 1980 Omeljan Pritsak, one of the most thought-provoking Ukrainian historians of the twentieth century, the founding director of the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, suggested rethinking Ukrainian history as ‘crossroads of various cultures and religions’. He saw the historian’s task as an obligation to study the past of all human communities and states on the territory of present-day Ukraine without limiting it to the Ukrainian core. As Pritsak argued, ‘within such an approach, the Tatars are no longer alien robbers, but on a par with the Zaporozhian Cossacks, our ancestors’.

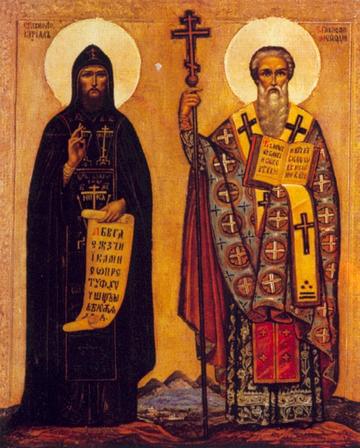

An Eastern Orthodox Icon depicting Equal-to-apostles Cyril and Methodius brothers as the Christian Saints.

In post-Soviet Ukrainian historiography Pritsak’s suggestion was supported by Yaroslav Dashkevych, who offered an interpretation of the ‘Great Frontier’ of Ukraine from the fourteenth century to the eighteenth as ‘a zone of diverse ethnic contacts, which functioned on the principle of selective filter (but not sanitary cordon)’ and claimed that historians ‘have no reason to contrast settlement and nomadism in the border zones of the Great Frontier: they did not oppose each other, but were mutually complementary’.

Broadly speaking, the success of the formula ‘between East and West’ has to do with a general redefinition of borderlands. At the beginning of the twentieth century, many historians still viewed this notion as rather derogatory and even tragic. Such approaches, however, were replaced by newer conceptualizations of “frontierness” as a blessing. In his programmatic article of 1995, Does Ukraine Have a History?, Mark von Hagen formulated a new motto for Ukrainian studies: ‘Ukraine represents a case of a national culture with extremely permeable frontiers, but a case that perhaps corresponds to postmodern political developments…In other words, what has been perceived as the ‘weakness’ of Ukrainian history or its ‘defects’ when measured against the putative standards of west European states such as France and Britain, ought to be turned into ‘strengths’ for a new historiography. Precisely the fluidity of frontiers, the permeability of cultures, the historic multi-ethnic society is what could make Ukrainian history a very ‘modern’ field of inquiry’.

Temple Synagogue in Lviv, Ukraine, first built in the 17th century and then rebuilt in 1845. This photo was taken in the early 20th century before it was destroyed by the Nazis in 1941.

Nowadays ‘borderlands’ and ‘multi-cultural communities’ are discovered and described virtually everywhere. What brought about the broad acceptance of this recent historiographical commonplace? One may argue that various non-Ukrainian ethnic and religious groups have obtained a much more visible place in the histories of certain cities and regions. The complex and stereotype-overloaded Jewish-Ukrainian history became a major theme in some exemplarily nuanced publications on the history of revolutionary years of 1917-1921, in thought-provoking narratives about Ukrainian writers of Jewish origin and images of Jews in Ukrainian literature, as well as in powerfully argued essays on the Holocaust and its diverse legacies.

SS paramilitaries murder Jewish civilians, including a mother and her child, in 1942, in Ivanhorod, Ukraine.

The political contexts and subtexts of the openness/closure of the national narrative and the integration of this or that non-Ukrainian history are manifest in the example of the Crimean Tatars. Aggressive rhetoric about the Crimean Tatars as ‘robbers’ and ‘traitors’ was widespread in both Soviet and diasporic Ukrainian historiographies. Recently, the Russian annexation of Crimea triggered the deconstruction of anti-Tatar stereotypes and the myths of their ‘irreconcilable enmity’ with the Cossacks.

Starved peasants on a street in Kharkiv, 1933.

The notion of being situated ‘between East and West’ became one of the key metaphors in accounts of Polish-Ukrainian and Russian-Ukrainian relations. In the first case, Ukraine tended to be identified with the ‘East’, and in the second case with the ‘West’. The main difficulty in the construction of a reconciled Polish-Ukrainian narrative was the fact that, on the one hand, Poland was presented as a ‘gateway to the West’, whence Renaissance, Reformation and Counter-Reformation came to Ukraine. On the other hand, the Cossacks, a central phenomenon of early modern Ukrainian history, were mostly hostile to the Polish state, declared themselves the defenders of Orthodoxy, and played an important role in the weakening of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and in the turn of Cossack autonomy towards Moscow. In other words, the price to pay for the ‘Europeanization’ of Ukrainian history through the adoption of a positive image of the Polish-Lithanian Rzeczpospolita (even as a ‘prototype of the European Union’) should be a profound rethinking of the image of the Cossacks as one of the foundational myths of the Ukrainian national movement.

People cross a destroyed bridge as they evacuate the city of Irpin, northwest of Kyiv, during heavy shelling and bombing on March 5, 2022, 10 days after Russia launched a military invasion of Ukraine. (Aris Messinis/AFP/TI).

Probably the most difficult task was to construct a historical narrative of Ukrainian-Russian relations. And it became even more difficult in the context of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russian troops that started on 24 February 2022 with all its accompanying atrocities. It is indicative that so far, the most significant edited volumes, monographs and synthetic overviews of Ukrainian-Russian relations have been published in English or German, not in Ukrainian or Russian.

In the context of Russian-Ukrainian history, or more precisely, the history of the Russian Empire, the question of colonialism has been raised more than once. The topic, which initially seemed progressive and unconditionally Marxist, had been redefined by the mid-1930s as ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism’. The colonial and post-colonial themes re-emerged in post-Soviet times, interestingly, in the publications of Ukrainian historians who made their careers in the west and who argued for the integration of recent post-colonial frameworks within the Ukrainian context. In 1997 Serhy Yekelchyk observed: ‘Not a classic colony, Ukraine produced an ambiguous postcolonial condition. Some of its salient anxieties, like the obsessive and ultimately impossible elucidation of the precise location of the nation between Europe and its definitely non-Ukrainian but elusive “Other”, may constitute a paradigmatic postcolonial concern, possibly not so noticeable in “classic” cases’.

Further elaboration and critical analysis of the potential for post-colonial readings of Ukrainian-Russian relations is one of the most important tasks for future historians.

Andrii Portnov is Professor of Entangled History of Ukraine at the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder).