When is a Parliament not a Parliament? The Polish-Lithuanian Sejm and Parliamentary Culture

The English have never thought much of the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm. Already in 1598 John Peyton, identified recently as the author of an extensive report on the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth prepared for James I, observed that the Sejm was faction-ridden, and marvelled that ‘according to the auncient custome of the Northern nations, whose power is in their fyste, they come into the Senate armed’. Peyton expressed surprise that ‘considering the deadly feude of greate familyes and the virulent inveighing against them they comme not to strokes to the manifeste ruine of the state’. He scoffed at the slowness of deliberations on account of ‘tedious orations in both howses’—the Senate and the Chamber of Envoys—and that, on account of the principle of unanimity that governed debate, ‘matters for the publike goode (especially yf they bringe with them any charge) are not very easeley concluded’.

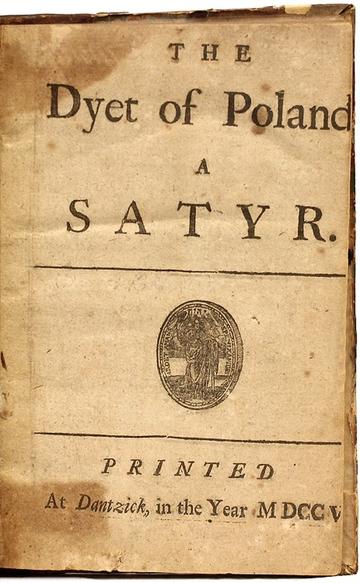

By 1700, when the notorious Liberum Veto—the logical extension of the principle of unanimity, by which the objection of one envoy could not only block legislation, but could break the Sejm—had become institutionalised, the Sejm was a laughing stock. Daniel Defoe’s 1705 The Dyet of Poland. A Satyr was an allegorical attack on the high Tories, above all the Earl of Nottingham and the Duke of Buckingham, who had been instrumental in sending Defoe to Newgate Prison in 1703. The target is English politics, but the satire works on account of Defoe’s adroit use of the Sejm’s reputation as a chaotic apology for a parliament: ‘How little some Men said, how some too much/How some….Cavil, Contrive, make speeches, and Debate,/And Jest too much with Poland’s dang’rous State./Prespost’rous lawes, absurd in their Design,/And made in Purpose to be broke, bring in;/Divide in order to Consolidate,/And tack Destruction to the wounded State.

Title page of Daniel Defoe’s The Dyet of Poland. A Satyr, London (and not Danzig, as the title page suggests), 1705.

Poland was just an extreme example. English historians have traditionally been rude about all parliaments, except their own. Lewis Namier, founder of the History of Parliament, was himself a Pole before he became a British subject in 1913, but his opinion of European parliaments was low:

Parliamentary government has been tried in every country on the European Continent and practically everywhere has broken down. Counterfeits of organic creations do not work: the bones may be brought together bone to bone and be covered with sinews, flesh and skin; but no breath will breathe upon them. Nations and individuals can borrow and use devices of a more or less mechanical character. They cannot usefully borrow and properly use institutions which depend for their life and functioning on the social organism which…has produced them.

For Namier, the Westminster Parliament was unique ‘because “organically” generated in the people’s past’.

Here is an example of the British exceptionalism that has bedevilled the study of parliaments. The idealisation of the self-appointed ‘Mother of Parliaments’ created a tradition in which proper parliamentary government was discovered on the banks of the Thames and exported to the British Empire, to flourish—in the USA and the white dominions at least. Europe, as Namier suggests, did not have proper parliaments. It had ‘diets’. The French even called their law courts parlements, but they were not proper parliaments, and the Estates General did not meet after1614 in the most famous example of the ‘eclipse of the estates’ as absolute monarchs across Europe supposedly crushed or abolished their estates bodies. Only in Britain was Parliament capable of resisting, decapitating one monarch who dared to try the continental recipe, and gloriously driving his son from the throne in 1688.

This distinction appears in the title of A.R. Myers’s 1975 Parliaments and Estates in Europe to 1789. Myers writes off the Sejm, which he presents as: ‘a particularly telling example of the evils of government by Diets’. ‘Diets’, note, not ‘Parliaments’. And ‘a particularly telling example’, suggesting that there were others. The implication is clear: if an assembly does not do things as the English do things, then it cannot possibly aspire to the lofty title of ‘parliament’, and can only be termed a ‘diet’ or an ‘estates body’. This distinction justified Namier’s dismissal of the Sejm. He suggested that in 1789, apart from what he insisted on terming ‘England’ only two nations in Europe could look back on an unbroken parliamentary tradition: Poland and Hungary. ‘These, however, were of a single Estate or caste: the gentry, a very numerous body…yet an exclusive, privileged class’.

Jacub Lauri, The Polish Sejm in 1622, Wikimedia Commons.

The landed classes in Britain, which Namier venerated, in stark contrast to his attitude towards the Polish landed classes of which he himself was a product, dominated the eighteenth-century British parliament, as he scrupulously demonstrated, yet that reality did not disturb him. It is high time, however, to question the assumptions behind this Anglocentric history of parliaments, in which the very word may be unhelpful. For assemblies were embedded in political systems across Europe in this period in a kaleidoscopic variety of forms, all of which grew organically out of societies that were often very different from that of England. In a period in which the concept of communities of the realm emerged to challenge notions of patrimonial kingship, these assemblies sought to embody the Roman Law principle of quod omnes tangit ab omnibus tractari et approbari debet: ‘that which touches all should be discussed and approved by all’.

‘All’ did not, of course, mean ‘all’. It meant the populus, those deemed citizens, which in Poland-Lithuania or Hungary meant nobles; in England it meant those who owned landed or urban property above a certain value: the famous forty-shilling freeholders in the countryside. To avoid the problem of the positive and negative connotations of the terms ‘parliament’ and ‘diet’ in the traditional scholarship, and of anachronistic claims concerning the origins of modern democracy, it might be better to talk of consensual systems, in which assemblies of various types sought the consensus that was necessary for the exercise of power. Inevitably their cultures differed, for the manner in which that consensus was reached varied as widely as the social and political systems of early modern Europe.

The origins of the Sejm were very different from the origins of the Westminster parliament. Myers, whose account is littered with misconceptions and errors, is wrong to talk of the Sejm as the embodiment of the ‘evils of government by Diet’, for although parliamentary government was indeed the solution to the problem of securing consensus that emerged in eighteenth-century Britain, the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm did not seek to govern. In the classical and Renaissance theory of the mixed form of government, which formed the intellectual basis of the Polish-Lithuanian Republic, government was a matter for the king, subject to the advice and oversight of the aristocratic part of the constitution, the Senate, which formed both the upper house of the Sejm, and the royal council.

The sejmiks and the local self-government remained the bedrock of the Polish-Lithuanian political system until the partitions. Though certain of their powers were reduced after 1717, their position was confirmed and in some respects strengthened in the Constitution of 3rd May 1791. Wikimedia Commons.

Poland-Lithuania was a republic whose political system was built from below in contrast to the highly centralised English state. The first institutions from which monarchs had to seek consent were the sejmiks, not the sejm. These were local and provincial assemblies that embodied the principle of Renaissance self-government. Their powers, granted in the 1454 Nieszawa Privileges, predated the emergence of a central Sejm. Members of the Chamber of Envoys were delegates of the sejmiks, not representatives of their constituents, as in Britain. They were issued with instructions, and had to report back to relational sejmiks to justify their actions at the Sejm.

Thus the culture of the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm was very different from that of the Westminster parliament, and it should not be judged for failing to be what it never tried to be. This project explores the different cultures of Europe’s consensual assemblies in the early modern period, to uncover the roots of contemporary parliamentary culture. It embraces those differences and seeks to explain them. The principle of unanimity in the Polish-Lithuanian Sejm emerged as a consequence of its organic connection with the sejmiks. It is a principle still alive in the European Council of Ministers. That the Sejm experienced a deep crisis in the eighteenth century is incontestable, but all consensual assemblies experience such crises, and the Liberum Veto was no more absurd than the institution of the filibuster in the US Congress, in which honourable representatives read out recipes, or passages from Longfellow or Proust, to talk out bills they do not like. Yet in the end, the Sejm reformed itself in 1791. The capacity to regenerate after a period of decline is the true test of a consensual system.

Robert Frost, Professor and Burnett Fletcher Chair of History, University of Aberdeen.