Max Weber’s Influence on German Economic Thought in the Twentieth Century

Max Weber (1864-1920) is primarily remembered for his contributions to sociology, history and politics and is widely recognised as one of the founding fathers of the discipline of sociology itself. Though his legacy in the field of economics has also been acknowledged, Weber’s direct and indirect influence on German economic thought has largely been overlooked. Michel Foucault hinted at this connection in his lectures at the Collège de France in 1978-9 in stating that:

Max Weber’s problem, and the problem he introduced into German sociological, economic, and political reflection at the same time...is the problem of the irrational rationality of capitalist society...And we can say roughly that the Frankfurt School as well as the Freiburg School, Horkheimer as well as Eucken, have simply taken up this problem...

Taking this statement as a starting point, I recently published an article examining the ideational parallels between, and engagement of, the Freiburg School of Economics with Max Weber. This school of economic thought, as well as individuals such as Alexander Rüstow (1885-1963) Wilhelm Röpke (1899-1966), and Alfred Müller-Armack (1901-1978) contributed to the German variant of liberalism, or ‘ordoliberalism’. This guided post-war economic restructuring in Germany and established the foundation for the ‘Social Market Economy’, which is still considered to be the model for German economic decision making today.

The Freiburg School founded in the 1930s, consisted of academics such as Walter Eucken (1891-1950) and Franz Böhm (1895-1977), as well as Ludwig Erhard (1897-1977) who was Chancellor of West Germany from 1963 to 1966. They advocated against both laissez-faire capitalism and central planning, envisioning a ‘Third Way’ (not to be confused with Tony Blair’s use of the term) that transcended the mainstream economic paradigm. This encompassed a state-led competitive order embedded in a legal regulative framework. Their vision was informed by the culturally critical debates, or Kulturitik, of the early twentieth century which were influenced by Weber’s critical commentary on modernity, capitalism and socialism.

A meeting in 1958 with the ordoliberal academic Alfred Müller-Armack (left), the head of the World Bank at the time Eugene R. Black (middle) and Ludwig Erhard (right) who was vice-chancellor and finance minister of Germany at the time.

Weber’s analysis of the irrational rationality of capitalist society in Economy and Society was particularly significant. He explained that the substantive needs of life, human happiness and social cohesion, were largely irreconcilable with the amoral mechanism of the capitalist system. Weber termed this irrationality the ‘spirit’ of modern capitalism, a specific ethic that emerged from the socio-moral conditions of the West. In his influential The Protestant Ethic and The Spirit of Capitalism (1905), Weber traced this ‘spirit’ back to the Protestant Reformation and the development of Puritan sects that resulted in an upheaval of social and cultural norms.

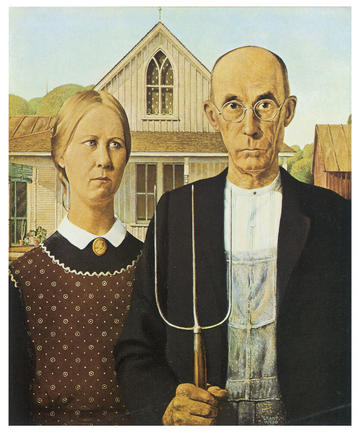

Grant Wood's 'American Gothic '(1930) is said to embody the Protestant work ethic in visual form.

Equally important to the debates of the early twentieth century were Weber’s reflections on central planning and his contribution to the socialist calculation debate. Though Weber saw modern capitalism pushing society into a stahlhartes Gehäuse, or ‘steel hard casing’, of bureaucracy, Weber considered central planning, particularly socialism, as a mere extension of this bureaucratisation and rationalisation. In a centrally planned system the socialist individual, just as the modern capitalist, would lose their personal autonomy to the bureaucratic machine. Weber came to the same conclusion as Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973) in the socialist calculation debate pertaining to the economic feasibility of a planned economy. Like Mises, Weber could not imagine a scenario in which a socialist economic system was able to function rationally and provide optimal results.

Ordoliberal thinkers echoed these debates in their own writings, at times even using similar language and directly engaging with Weber’s work. Eucken himself was a student of Alfred Weber, Max Weber’s younger brother with whom, intellectually, Alfred shared much in common. Rüstow mentioned Weber frequently in a lecture published in 1943 in which he traced the modern drive for incessant profit making to the rationalisation of ‘inner worldly’ asceticism as a consequence of the Reformation, stating that ‘this work stands with gratitude and admiration on the shoulders of Max Weber’. Röpke similarly engaged with genealogical studies in a Weberian framework, recognising that ‘Max Weber has drawn attention to the especial influence of Calvinism on the growth of the business spirit’. Röpke explored how the Reformation resulted in collective societal alienation since the post-Reformation Christian ‘must turn his thoughts more devoutly inward to his own soul and its salvation’ which increased the disconnect between the individual and society.

The ordoliberals were thus just as disillusioned as Weber was a few decades earlier with the modern manifestation of capitalism. They were equally as critical of socialism and central planning using arguments akin to Weber’s of the inability of a socialist system to provide rational and efficient social and economic results. They thus sought a ‘Third Way’, a term first used by Röpke in 1942, that envisioned a consciously shaped market that was guided by regulation rather than blind adherence to the market mechanism and the invisible hand or central planning. They also sought to revitalise the disillusioned capitalist worker stuck in the ‘steel hard casing’ of modernity with their Vitalpolitik, or ‘vital policy’. Through economic restructuring and social policy, especially education policy, Vitalpolitik aimed to improve the vitality and autonomy of the worker, enabling them to pursue self-interested goals that also ensured the social well-being of the community.

Angela Merkel celebrating what would have been Walter Eucken's 125th birthday in January 2016.

Despite the, at times, radical, conservative and romantic ideas these ordoliberals espoused, the core of their ideas, specifically the integration of society and the economy through a framework of regulation, took root in Germany, which some argue contributed to the Wirtschaftswunder in the 1950s. Though the ordoliberals were informed by the debates Weber sparked decades earlier, the utopian ideals they fostered were at odds with Weber’s cynicism. They sought to break out of the bureaucratic structures of rationalised society to build a new, individualised and spiritually fulfilled order.

Isabel Oakes is reading for DPhil in History at Lincoln College, Oxford. You can read her latest article in the Journal of Contextual Economics here.