Power over the most Powerful: The Paradox of Parliamentarism

Consent, we are often told, is what set premodern European political institutions apart. The parliamentary tradition was an outgrowth of many factors that converged only at a certain time and place. Even there, some polities fostered a culture of consent more effectively than others. England is the typical example, with its unrivaled parliamentary record dating back to the thirteenth century with only an 11-year interruption. The Netherlands also had remarkably robust institutions. And Poland had traditions of a democratic character that were not achieved until the twentieth century in the other cases: its kings were typically elected and the liberum veto took the democratic principle of “what touches all must be approved by all” to its logical conclusion: without consent by all, there could be no action.

“Great Sejm” of 1791, from Kazimierz Wojniakowski, The Passing of the 3rd of May Constitution, 1791, Wikimedia Commons.

Against these models of consensual politics have stood the polities believed to stifle consent, the absolutist monarchies that serve as powerful reminders that geography or common culture alone does not guarantee any given path, with France offering the classic exemplar, but Castile, the Holy Roman Empire, and many others on their side. The starkest contrast of course has been with the non-western “Other,” for instance tsarist Russia or the “sultanic” Ottoman Empire. Historians, however, have long deconstructed the notion of western “absolutism,” to illuminate the weak infrastructural control rulers actually had over society.

What can the period of origins, before 1500, tell us about these divergent paths towards parliamentarism? In fact, weak infrastructural power was a condition that long predated the victory of “absolutism” itself, going back to the medieval period, when these institutions first emerged. We can go further. If one actually tabulates the numbers of assemblies held in France to include not only the Estates-General but the many meetings with nobles or towns alone until 1350, and then compare those with the English Parliament, France emerges as having engaged in more “consent-seeking” than England! Up until the French Revolution, as Tocqueville noted, there were at least twenty-five local assemblies that regularly met and handled taxation.

The difference between “constitutional” England and “absolutist” France can thus be seen as the optical effect produced when consent is negotiated centrally, in Parliament, where one can easily observe it in a summary way. Consent was not absent in the other, later called “absolutist,” polities; instead, it was exercised (and often denied) in an infinite number of local contestations. Even in the Ottoman Empire, when monks on Mount Athos faced dispossession by Selîm II in 1568, they threatened to “sell our possessions…and scatter all around the world,” depriving the Sultan of precious taxes. The Sultan promptly relented. His English counterpart, Henry VIII, proceeded with the largest expropriation of land in premodern Europe, the Dissolution of the Monasteries, with Parliament giving it a stamp of approval.

However, such locational difference had profound long-lasting implications: the centralization of consent-seeking allowed social groups to solve their collective action problem and act in relative unity, which, in the long-term, allowed them to effectively shape and limit the power of the ruler. England became the beacon of liberal constitutionalism, France and the Ottoman Empire did not. Where consent was not effectively centralized, absolutism prevailed and radical change, even revolution, were necessary to eventually install constitutional and democratic structures.

We do not need to accept any kind of historical determinism to admit that this divergence must have had something to do with the fact that the English Parliament was, already by the fourteenth century, not only aggregating grievances from both town and country in the form of petitions but also proposing the legislation meant to address them. But this gives rise to a number of paradoxes, which might be described as a “normative/empirical inversion:” outcomes that are assumed to be definitional of parliamentary structures, such as the limiting of central authority, often have their origins in conditions that are their opposite. For instance, where one sees institutionalized limits to central authority, as eventually in England, there was strong central power initially; conversely, where one sees radical demands or practices that accord with modern democratic sensibilities, as in France or Poland, polity-wide parliamentary structures did not survive to shape the regime into the modern period. No monocausal thesis can explain this, but a pattern exists.

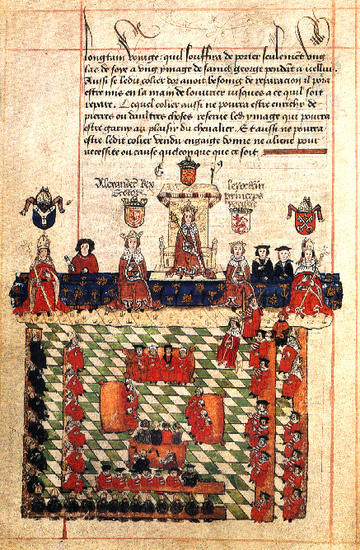

Edward I presiding over parliament in c.1278, from the Garter Book, written and illustrated by Sir Thomas Wriothesley in c.1524, Wikimedia Commons.

We might probe this paradox further by considering a point that is widely understood in medieval English historiography but perhaps not as well elsewhere, certainly not in the social sciences that are now turning with new-found interest to the period of origins: medieval English kings were probably the strongest rulers in Europe as far as their powers over their subjects were concerned. This is why, after all, as Joseph Strayer noted, they could match the French “man for man” and “pound for pound” already in the 1290s, despite having less than a third of their population and much less than a fourth of its wealth.

We can now see that this was not an aberration but a systematic pattern that set English extractive capacity at three to four times the per capita levels of France between 1200 and 1498, when the two countries were developing their representative institutions (the balance reversed slowly after that, but reverted once again after the 1660s, with higher per capita English taxing powers noted with approval by no less than Adam Smith himself in 1776). We tend to think of parliamentary traditions as limiting the capacity of rulers to tax, but this has oddly normalized a conservative anti-tax premise into an analytical historical assumption: that democratic limits must mean fewer taxes. In fact, historically, the strongest representative institutions were typically those that taxed the heaviest. Holland even surpassed England in this regard.

The Great Assembly of the States General in 1651, attributed to Bartholomeus van Bassen, Mauritshuis, The Hague.

Why this ruler power mattered further becomes obvious when we note another important “inversion:” representation, which we now consider to be the sacrosanct right of democracy, was originally an obligation before it became a right. The point was long hotly contested until about half a century ago, not least because it was assumed to ensconce a conservative and condescending delimitation of the powers of the Commons in the present day. With those polemics now subsided, the role of obligation is clear: representation was in fact similar to jury duty originally. Representatives in England (and some, but not many, other European cases) were summoned by the king and forced to come with full plenipotentiary powers to bind the community that sent them. In France, Poland, Hungary, Castile and elsewhere, many representatives came armed only with “imperative mandates” from their communities to “hear and report”—indicating far greater powers of autonomy for the local communities. But that is where polity-wide representative assemblies did not survive into the modern period. This might not be a comfortable conclusion, and its causes may be multifarious, but it is one that the historical record forces us to consider.

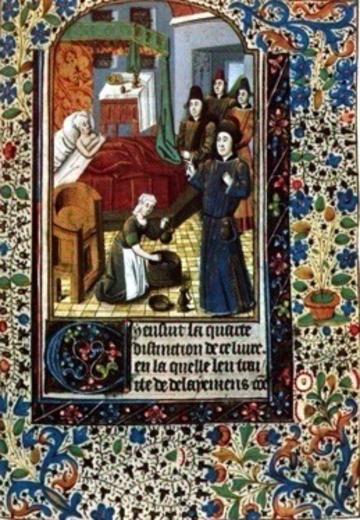

Visit to a sickroom. This medieval manuscript illumination represents the procedure followed when a defendant was too sick to attend court. It shows the strength of enforcement of court obligations. A bailiff, accompanied by four knights and eight honest men above suspicion, visited the sick to verify his illness. It is from the Coustumes de Normendie, from the 15thc, in the Library of Congress (folios 77 and 81r to 82r).

Another way such an inversion was crucial concerns the role of the nobility. Strong ruler power meant that when English historians lament that English kings could secure attendance from “no more than” a third of the nobles they summoned, we need to note that in absolute numbers this was higher than what the (admittedly extremely scant) records of parliamentary attendance in France suggest, despite England having a third of the population. This disparity mattered. Although we (rightly) think of representation as the victory of the popular element over noble privilege, the conditions of emergence were again inverted: it is when nobles were more effectively summoned to parliament and taxed that institutions acquired not only regularity but inclusiveness. There are many differences between England, France, and Castile, for instance, that account for why the former retained a constitutional structure but the latter two are identified as “absolutist;” but it is not an accident that England was quite unique in its powers to compel the nobility, at least originally, in the period of institutional origins. One must note however that the explanandum here is institutions that legislated by aggregating grievances from across society, not just any type of assembly.

Why might that matter? Because only when the ruler had the capacity to compel the nobility did he also have access over the populations under their jurisdiction. That Castilian kings did not at least partly explains why the precocious representative activity that did occur involved only the cities. Indeed, the Castilian Cortes continued to meet whilst the French Estates-General lapsed but this did not prevent the regime from being classified as absolutist: most of the population was deprived of representation.

The other reason why ruler power, especially over the most powerful, mattered is connected to another feature of parliaments that is sometimes sidestepped, not so in history but in the social sciences: the English Parliament was also a court of justice, as were many similar institutions on the Continent. This is where the petitions were submitted, which, eventually, were transformed into legislation. We can’t really explain parliaments as legislatures without engaging with this process. We tend to associate parliaments with war and taxation, but the frequencies of assemblies that met to discuss fiscal/military matters was very low in the early period of institutional formation (the 13th and 14th centuries). You can’t get a regular institution from an irregular imposition. Requests for justice, by contrast, were a constant, daily, bottom-up demand that brought the people together in the king’s courts.

This point helps us explain the curious divergence between the English Parliament and its originally twin institution, the Paris Parlement. Both were off-shoots of the King’s Council with multiple duties, including judicial ones. Yet the English one became a primarily political institution whilst also serving as the supreme court of the realm (until 2005), while the French one retained only the judicial functions. Why? Among many reasons, the English Parliament was regularly attended by the nobility because the English kings succeeded in compelling them to participate in the hearing of petitions, so much so that before long (the early 1300s) nobles were effectively coopting the institution. But this meant that when taxes were required, a regular forum that concentrated all social groups, especially the most powerful ones, was ready at hand. In France, the king was faced with powerful subjects who typically defied his orders, so the similar offshoot of the King’s Council—the Paris Parlement—had to be staffed with paid officials, not nobles, to hear petitions. So when taxes were needed, different institutions needed to be created, the Estates-General. Since fiscal demands were not layered on a regular judicial institution, fiscal meetings lacked regularity, social groups did not meet under a common set of obligations to solve their collective action problems, and the Estates-General eventually faltered. However, the Parlement’s regular judicial duties ensured it a continuity that rivaled that of the English Parliament, up until the French Revolution. We think of the separation of powers as a core constitutional principle, but fusion of powers seems a more effective route in the period of origins.

Jean Fouquet, Lit de Justice at the Paris Parlement held by Charles VII of France. (c.1450), Wikimedia Commons.

This judicial/fiscal layering was hardly unique to England. The Polish Sejm passed laws in the early 1500s asking kings to “hold regular judicial sessions twice a week . . .during the Seym debates so that the two might overlap” and so that adjudication did not lag. Nor were petitions exclusive to England and France. They were a universal medium for the expression of grievance since antiquity, and they saw an efflorescence throughout Europe especially after the 1270s, from Castile, to Flanders, to Hungary. We cannot trace the emergence of legislative institutions, nor identify their differences from other aspects of Europe’s participatory culture, without understanding how petitions were aggregated and processed in different polities. English petitions have already received admirable attention and their counterparts in Flanders, France and beyond are increasingly being explored. But restoring justice and petitions to their rightful place in the study of Europe’s parliamentary culture not only expands our understanding beyond “the fiscal state” which has long dominated many approaches, it also opens up a new basis of comparison with the “non-West:” petitions and justice were as central to the Russian tsar as they were to the Ottoman sultans, who were obligated to dispense justice to their subjects. These two basic building blocks of European parliamentary culture were not unique to it. Other cultures did not lack the demand for rights or justice. If we are to properly understand what differentiated the European experience, we need to move beyond the concepts of consent and rights. From one perspective at least, it is the greater capacity of European, especially English, rulers to impose collective obligations on their subjects that generated the collective action that generated legislative institutions, though perhaps not its rich parliamentary culture. But this complex question will repay study from an interdisciplinary cross-national perspective.

Ottoman Imperial Council Reception of the French ambassador by the Grand Vizier and the Imperial Council in 1724, Wikipedia Public Domain.

Deborah Boucoyannis, Department of Political Science, George Washington University.