Exported Early Modern British Political Cultures

The search for early modern European representative culture can be profitably pursued beyond the European mainland into the colonies being established in North and South America in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. There, in the extractive ‘settler colonies’ occupied by European immigrants, new governments were being created, reifying European ideas of political representation. In British North America and the Caribbean they copied the “Westminster” model with landholders given voice in assemblies. Strikingly, these British colonies were not urban, and their settlement and governments rested on the Common Law idea that land was power emanating from the Monarch. In Spanish American colonies where, as Jorge Díaz Ceballos tells us, the power of the king emanated from the towns, the latter had no need of indirect representation through the Cortes. These cities’ procuradores represented them directly to the Spanish crown. In French colonies the French crown did not provide local representative assemblies, in keeping with the decline of the Estates General in the home nation.

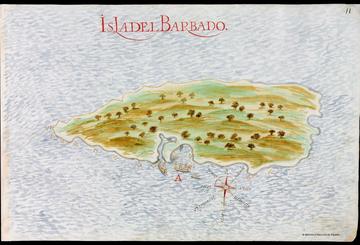

Spanish map of Barbados, 1632.

The presumptions of these settlers about what governance should be like reflected their political cultures at home. Interns of the University of Oxford's micro-internship programme working with me have been mapping the representative governance in Britain’s American colonies from Acadia in the North to Barbados in the far South. What we found was a mix of political institutions that all mirrored, sometimes distortedly, English ideas of what governance looked like. The correlations between them and the national political system varied, however, depending on the kinds of colonies they were, whether corporate colonies (in which a group of shareholders invested under license from the king and ruled through the corporate board), proprietary (in which the monarch granted an individual a colony, such as Pennsylvania or Maryland, which were ruled by the proprietor), or Royal colonies in which the King took a direct governing role through an appointed governor. Over time, all British colonies tended to turn into royal colonies, as settlement increased and locally born elites emerged. In the early 17th century the corporate model predominated; later establishments were proprietary or royal.

Limited by the digital sources available during Covid lockdowns, the micro-interns have explored the colonies using documents in the Avalon Project’s database of constitutional records and in the digital edition of the British Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, North America and West Indies. What they discovered confirms that beliefs do echo home cultures, but the realities of colonial life and the types of establishments made, whether corporate, proprietary or royal, slave economy or not, or under more than one crown made important differences.

John Seller Map of New England, 1675. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library.

British colonial governments were established on English law. As the 1629 Charter of New England said, all the inhabitants born there had the rights of Englishmen and its 'general Court', whose functions included the settling of disputes and making laws, could only act 'so as such Laws and Ordinances be not contrary or repugnant to the Lawes and Statutes of this our Realm of England'. Interestingly, there was little need for colonial bicameral representative institutions when the assemblies sent their decisions to councils of various sorts in London, and when appeal was often to the Privy Council.

Take, for instance, the established ‘Body corporate and politique’ of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The colony was chartered in 1609, but the re-foundation of 1629 remained in place until 1691. The 1629 charter created an administrative structure of a Governor and his Council, and a legislative/legal General Court. The General Court had the job of settling disputes and legislating ‘for the good and Welfare of the said Company, and for the Government and ordering of the said lands and plantation, and the people inhabiting…the same’.

The ‘people inhabiting’ Massachusetts had little say in General Court. Elected by the freemen of the Company, it left the colony in the hands of a small group. Although the councilors were elected annually, ‘yet it is done in such a manner as the people have not any voice’. Freemen of the right religion were enfranchised, and no others. The freeholders, defined in New England as ‘the principal Knights and Gentlemen Adventurers… and…divers other Persons of Quality’, were, as in England, a narrow elite. This mimicked the English system, in which only men of property, the ‘forty-shilling freeholders’, could participate in elections. In that sense, English oligarchic representation was transplanted to Massachusetts.

King Charles II in coronation robes by John Michael Wright.

Not surprisingly, the British Civil Wars were echoed in the colonies. The wars, the Interregnum, and the Restoration all played out on the western side of the Atlantic, changing the calculus of political representation. In New England this was especially true after the Restoration. The attempts by Charles II to impose the Book of Common Prayer on Massachusetts and to stamp out Dissenters, disputes over the Colony’s right to coin money, the Navigation Acts, and the ‘illegal’ war declared by the Colony on the Sachem ‘King Phillip’, led to the 1684 revocation of the Charter of 1629 and the imposition of a new one, reducing the Colony’s independence.

Massachusetts’ complicated relationship to the Crown was reflected in the genre of election sermons. Ministers, usually from the founding freeholders like the Mathers, preached on election days, often emphasizing the value of political representation, striking notes that were sometimes at odds with English ideas of legitimation of authority. As the Rev. John Norton said, ‘This Power of Rulers of the Common-wealth is derived from the Peoples free Choice’. These election sermons also stressed the duty to work together to maintain the ‘hedge’ that protected the community, often proven through biblical stories. We can see in these sermons instances of what Edmund Morgan called ‘the invention of the people’ as a source of political legitimacy.

Virginia, too, evolved with the times across the seventeenth century. The Virginia Company Charter of 1606 had licensed a group of investors, ‘Knights, Gentlemen, Merchants, and other Adventurers’, to settle there and exploit any resources they might find. Their greatest export quickly came to be tobacco. The original Virginia settlements had a bicameral Transatlantic government, with a Council of thirteen Virginia freeholders resident there, and another Council of thirteen in London.

This 1606 charter proved to be unworkable, and in 1624 James I re-chartered Virginia with a royally appointed Governor, a Council of State, and a ‘Grand Assembly’, later known as the House of Burgesses, made up of 40 representatives. Battling with the Crown over tobacco exports, the Assembly remained Royalist until a Parliamentary fleet forced its surrender in 1652. Accepting defeat, the Assembly extorted concessions from Cromwell, increasing it powers. The Restoration saw Virginia’s government re-modelled again with concessions from Charles II. A new second chamber, the ‘Lords Proprietors’, was added to the House of Burgesses. Thus, by the mid-seventeenth century the House of Burgesses was functioning as the bicameral Parliament of Virigina, using the same logic of authority as the Parliament of England. The franchise extended to all men who owned sufficient land, as in England.

Reconstructed Virginia House of Burgesses, built 1701-5. By Martin Kraft - Own work (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The growth in size and representation of Virginia’s House of Burgesses was normal for the colonies. In the beginning, the size of the electorate was tiny in these new colonies. For instance, in Rhode Island 39 men signed the document creating the Plantation’s governing Council of five. As the settlements grew, these governing institutions had to expand to incorporate representation based on land ownership.

One of the realities in the seventeenth century was mobility of people between the homeland and the colonies, so the extension of political assumptions was natural. And antipathies move, too. Religious discrimination against Catholics and Quakers was obvious, as was conflict between royalists and parliamentarians. In corporate colonies in New England the right to be represented might be about a man’s status in the covenanted church. In Crown colonies it depended more on the amount of land held, though religious conformity was also an issue. In proprietary colonies, such as Pennsylvania and Maryland, religion was less of an issue. In the more populous and richer colonies, representation moved toward the English model based on net worth rather than on acres. In the slave-holding colonies this was clearly the case since wealth in enslaved humans was large.

The execution of Quaker Mary Dyer, 1 June 1660. 19th century picture, The Granger Collection, New York.

The Colony of Barbados was founded in 1627, owned by Sir William Courteen. Proprietorship soon passed to Lord Carlisle, who appointed Henry Hawley governor. In a bid to get cooperation from the planters, he established the House of Assembly in 1639. The year after the Assembly was founded, the Dutch introduced sugar production to Barbados and sugar quickly took over the purpose and politics of the island. By 1650 Barbados, resenting Westminster’s attempts to limit trade, declared for Charles II and issued the ‘Barbadian Declaration of Independence’. This 1651 declaration established the right of ‘free-born Englishmen’ to self-governance. Naturally, the assertion of the rights of freemen said nothing of the rights of the enslaved people who were the majority population. Their presence was acknowledged by the political power of the Royal West Africa Company, the slave importer, in the Assembly. At one point, the Company’s representative was also the Speaker of the Assembly.

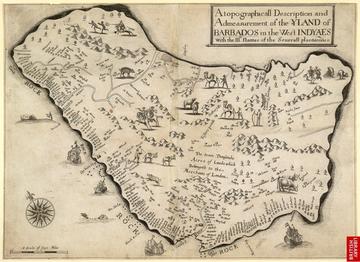

Map of the Island of Barbados (1657) showing the names of plantation owners. British Library.

The white men of Barbados were governed after the Restoration by a royal Governor, a twelve-member royal Council, and the 22 members of the House of Assembly, with each parish electing two representatives. Governor, Council, and Assembly together had the power to make statutes, echoing the English system. Ironically, in Barbados, where disease and discomfort made it hard to keep white settlers, there are signs that Jews and Quakers had more political voice than was common in English colonies. Quakers even held political office, though they were still discriminated against.

In the western Atlantic, English settlements assumed their political culture should look like that of England. Men who owned land had a right to participate in government and to elect representatives. Although the particulars varied from place to place, governance always assumed that the monarch or the monarch’s governor held executive authority, a council of the ‘best’ men advised the governor, and the landed men were represented by an assembly. Together they made laws for their colonies.

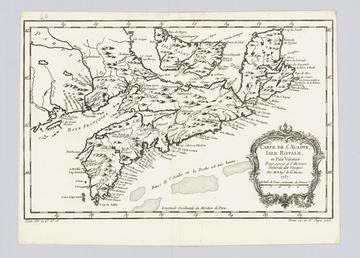

Map of Acadia, 1754.

How peculiarly English this was is underscored by Acadia. The colony of Acadia, also known as New France or Nova Scotia, was founded by the French in 1604. They transplanted the Seigneurial system of government from France into the colony, and it remained dominant despite later British rule. In the Seigneurial system, grants of land were made to families, who, in turn invited settlers to use the land in their ‘villages’ in exchange for rent. Therefore, the governance was in the hands of the heads of the landowning families. These land tenures were confirmed by the French Crown in 1627, when the Compagnie des Cent-Associés was chartered.

The Seigneurs were responsible for attracting settlers, resolving legal disputes, and other things. The Seigneurs also organized the diking and draining of the marshes in Acadia. This group effort did not require the introduction of ideas of representation into the Acadian community, since power remained in the landlords’ hands, as it did in British colonies. Moreover, the French crown had no interest in giving even its great and good voices in the seventeenth century. The highly structured meetings of the Estates General were suspended after 1614, as Sylvie Daubresse reminds us.

When Acadia was incorporated into the government of La Nouvelle-France in 1663, it had an Intendant, a governor, and a Conseil Souverain. The Sovereign Council included the Governor, the Intendant, the Bishop, the Captain of the Militia, and five Councilors appointed by the King. There was little about it that was representative of the Acadians. The other political power in Acadia was the Catholic Church. Parish priests were very important, as were the Jesuits and the Récollets, a Franciscan missionary group. When Britain took control of Acadia in 1713 it declared itself ‘sole seigneur’ of the Acadians and expected the locals to pay their taxes to His Britannic Majesty. British control meant a banning of Catholic priests, a strike at traditional, authoritarian government.

The Acadian political system was destroyed when the British deported three quarters of the Acadian population to other parts of America between 1755 and 1764. As in the Scottish Highlands and Lowlands, where the Clearances began at the same time, the deportations broke up the traditional family power bases. From the point of view of European political cultures exported to North America, Acadia represents a proof of the entrenched nature of political ideas. Whereas English settler landowners expected to be governed by representative institutions echoing Parliamentary structures, the French settlers did not. They imposed French seigneurial government and clung to it until it was physically destroyed by frustrated British rulers. In the British cases, the sorts of governance exported to the American colonies depended upon the founders’ assumptions about how local governance should work and the purposes for the foundation.

Norman Jones, Emeritus Professor of History, Utah State University.

*My thanks to the micro-interns who worked on this project: Joseph Beaden, Nicola Green, Oscar Patton, Lia Rockey, Benedict Stanley, Matilda Walters, Liana Warren.