The Proud Oxymorons of Venice’s Parliamentary Culture

Like the lion of St Mark, winged and advancing on water, like the very city built in the lagoon, Venetian parliamentary culture is full of paradoxes. Described with the Latin consilia (in the plural) rather than the French-derived parliament, a number of collective assemblies ruled Venice, ranging from few to several thousand members. They deliberated and voted on all home and foreign affairs. In the capital, a city that by 1600 reached nearly 200,000 inhabitants, they decided even the minutest aspects of urban administration. In the rest of the state – stretching from Northern Italy to the Eastern Mediterranean and including some six million subjects – they left strictly local affairs to yet more provincial assemblies, but elected and instructed governors and decided on all fiscal and defence policies. Like Parliament in England, they combined judicial with legislative powers, but there was never any discussion of their ‘prerogative’, essentially because everything belonged to them. Unsurprisingly, some councils were extremely busy, meeting almost daily as permanent institutions in the Ducal Palace. Conciliar activity was literally part of everyday life for their many members. Oscillating between 1500 and 2500 men in the early modern period, they were perhaps the largest group of people consistently engaging in government business in the world.

Vittore Carpaccio, Lion of St Mark, c. 1516. Wikipedia Commons. On the left is the Ducal Palace or Palace of St Mark, where the painting still hangs today. The building's layout is a useful guide to the working and mutual political relations to this day; it housed the doge in a small suite of rooms but above all hosted the numerous councils of the Republic.

Known as ‘patricians’ (again a reference to Rome), they were a minority, even if a large one, who had access to the councils by right of descent (from patrician families by father and also, since 1506, mother). Their culture was thus at once proudly republican and profoundly oligarchic. Republican, because all patricians were equals and each vote counted as much as the next. Sumptuary legislation ensured a degree of uniformity even in appearance, and strict legislation sought to prevent individuals from exerting undue influence. For example, rotation prevented officers from maintaining their functions for more than a certain time, with greater power corresponding to shorter tenure. On the other hand, this was an oligarchy. As the word suggests, patricians only included adult males, even though women and adolescents had substantial informal power in building and maintaining kin networks and alliances. And of course, the patriciate excluded most of the population. Elsewhere in Europe, civic assemblies included representatives of guilds; not so in Venice, where manual professions disqualified from patrician status (unsurprisingly, commerce did not). It is useful to insert institutional and intellectual history in their social context. In Venice this shows that aristocratic ideology justified political arrangements in terms of patrician selflessness, public devotion, wisdom and increasingly, birth and magnificence. In short, as historians recognise, Venice was an oligarchic republic – given the size of the ruling class, we could call it a ‘poligarchy’.

Antonio Diziani, The Great Council in session, 1758-63. Wikimedia Commons. The council gathered the entire body of the patriciate and met every Sunday; it elected most other officers and councillors in Venice. Note the identical robes, a uniform that was supposed to hide social and economic differences; the only exceptions were specially appointed officers. The children in the foreground carried the urns used to vote: their age was intended as a guarantee of innocence.

‘Oligarchic republic’ may seem an oxymoron today but made sense at the time to those who saw it as vital to Venice’s success. Many doubted the chronicles tracing the republic’s foundation to 421AD – though the sixteenth centenary is celebrated this year in a lavish exhibition. But they all knew that Venice survived when wars or factional conflict toppled most Italian Renaissance republics, and this in a city that has always been uniquely fragile (as this wonderful recent podcast reminds us). Many credited Venice’s exceptional resilience to conciliar arrangements. Some praised equality, like Marino Sanudo, a patrician who never obtained high office. To him, Venice’s cherished sovereignty rested on all patricians being sovereigns: no individual or group exercised excessive power, and conciliar debate led to the best decisions. This is why he and others also insisted on the importance of political participation, the active rather than the contemplative life, another recurring point in patrician political culture.

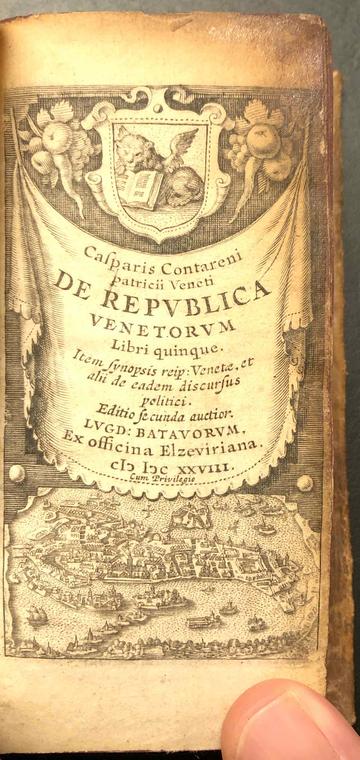

Others, like the much grander Gasparo Contarini, hailed Venice as the best example of mixed government, a prized ideal since Aristotle. The democratic element was the Great Council, which gathered all male patricians aged 25 or above (as well as some lucky eighteen-year-olds selected by lot every year.) Contarini called them simply cives, citizens: a term which exalted the civic spirit of patricians while disenfranchising the rest of the population. The Great Council elected the doge, the monarchical element, who derived his name from the Latin dux, but was less military leader than representative head. Appointed for life but usually in old age, he had important ceremonial functions and sway over other patricians but otherwise restricted power. The Great Council also elected most other offices and smaller councils, including the Council of Ten (which in fact had seventeen members!) and the Senate, so called (Contarini said) because it gathered the senes, or old men – an etymology justifying power in terms of wisdom and experience. Together, they made the aristocratic element. The balance of these parts prevented the decay of the body politic, just as the balance of humours ensured good physical health, a parallel which seemed natural at the time and which it would be worth exploring further. This was Venice’s answer to the disorder that observers throughout pre-modern Europe saw as synonymous with collective government. What made Venice exceptional in their eyes, was not that it was a republic but that it was peaceful despite being a republic. The cherished image of ‘the most serene republic’ was the true oxymoron, held proudly as an emblem.

Giovanni Bellini, Doge Leonardo Loredan, c. 1502, National Gallery, London. Wikimedia Commons. Recalling a marble bust, this portrait of richly attired doge Leonardo Loredan points to the double nature of the office: a selfless representative, yet an intense figure, ‘lifelike and immediate as well as distant and imposing’.

The notion of representation, a centrepiece of republican culture, is also slightly contradictory in Venice. The Great Council represented neither the entire population nor the patriciate, with which it rather coincided. Indeed, in the eyes of patrician men, patrician women and young men were not to be represented but ruled. Within these confines, the Great Council functioned as a direct democracy – but by the sixteenth century, it had above all voting and electoral functions, i.e. to pass or fail legislation or candidates proposed by other councils. Representation was therefore more of a feature for the other elements of government, including several offices who stood for the city’s six administrative units. The doge represented the state symbolically, and indeed most laws were published under his name. He also represented patrician unity and for this reason was chosen by a qualified majority of 41 electors, themselves chosen by the Great Council with a complicated system combining votes and lots. Sortition ensured an element of random and equal access, even though in fact the system was designed to guarantee the most prominent patricians a place among the 41 electors. As with the papal conclave, the electors then worked behind closed doors for days and sometimes weeks to conceal disagreements and divisions. For all this, the actual significance of the doge’s representativeness was questioned even at the time, when some contemporaries described him as no more than a tavern sign.

No one would have said this of the Senate or the Council of Ten. The former included some 250 members, including 120 who could be confirmed year after year, so as to allow a degree of continuity; the rest obtained membership ex officio, by virtue of other offices to which too they had been elected. The Senate never lost its functions as a deliberative assembly and continued to be the closest in function and activity to a sitting parliament. By contrast to the Great Council, which voted in silence, senators debated all major decisions and so really represented the differing opinions that naturally existed in the patriciate. This made for an interesting paradox. On the one hand, debating was a crucial skill for Venetian patricians, and deliberative rhetoric, a tool of political life. On the other, strict rules regulated debating so it would not unsettle the order of government or the power of those who set the day’s agenda; and even stricter secrecy maintained a façade of unanimity. Thus, secretaries recorded the audiences of foreign ambassadors verbatim, but took no minutes of the arguments voiced inside the Senate and in fact senators themselves were forbidden from bringing pen and paper into the hall. Such procedural rules mattered.

A half century ago, John Pocock underlined the importance of Venetian electoral arrangements in influencing modern republicanism as a system of ‘mechanized virtue’ intended to ensure that the common good triumphed over individual ambitions. But as I suggested in my book, Information and Communication in Venice, the preservation of secrecy had similarly important ideological functions, despite the infamous traits it acquired in nineteenth-century Romantic portrayals such as Lord Byron’s Marino Faliero. On the one hand it rendered groupings and factions less visible and influential, while in fact pushing them behind the scenes. On the other, it was meant to protect voting, the only form in which most patricians exercised their sovereign power free from outside pressures. Ballots were made of cloth, so that even in densely packed assembly halls no one could hear in which urn they had been deposed. In Venice, secrecy enabled a remarkable achievement: a government unique for its large power-sharing and complex deliberative process being renowned above all for its secrecy and harmony. But beyond Venice, a comparative analysis of such arrangements in European parliamentary institutions such as is researched in the Parliamentary Cultures Project would illuminate differences and similarities in social and political assumptions.

Pietro Malombra, Audience of the Spanish ambassador in the hall of the Collegio c. 1617, Museo del Prado. Wikimedia Commons. Ambassadors were received in the Collegio, where the doge sat surrounded by his counsellors; they addressed him as the representative head of the state, but all substantial answers and decisions were taken by the Senate, for which the Collegio worked as a steering cabinet – the door to the right connects their two halls. Such paintings abounded in the sixteenth and seventeenth century

Two final points complicate this picture in important ways. First, despite all these arrangements, an oligarchy within the oligarchy held an inordinate amount of power not because of experience or wisdom, but thanks to patron-client networks and wealth. Electoral rolls show that a relatively small number of individuals and families in every generation effectively monopolised the Ten and other powerful councils, to which they were returned time and again. Some councils dominated the agenda of larger ones, such as the Collegio, the Senate’s cabinet and a central government body which until recently escaped proper study by historians. The Council of Ten was instituted in 1310 in the wake of a thwarted conspiracy, as a sort of public safety committee, but remained in charge of state security and increased its powers until the end of the Republic in 1797. But this ‘inner core’ did not go unchallenged. There were regular rebellions in the patriciate, the most famous in 1582 and 1628, when the Great Council passed motions severely restricting the power of the Council of Ten. These and other occasions would require greater study, but what is certain is that political conflict – downplayed in the official façade but constant in reality – undermined secrecy. Patricians, secretaries and other professionals of information continued to discuss politics far beyond the halls of government in what in my book I call a ‘competitive political arena’ outside institutions. And what’s more, ordinary Venetians as well as foreigners had a keen interest in precious government information, for trade or profit or sheer curiosity – people even placed bets on the outcome of patrician elections.

Small pocket editions such as this tiny 1628 Elzevier made Contarini’s treatise on the Venetian constitution into a best-seller for the politically interested throughout Europe. Private collection.

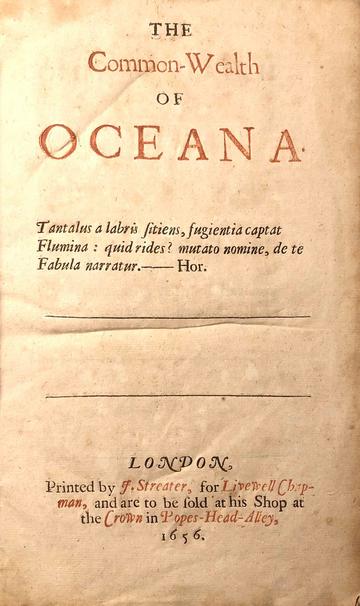

This curiosity is not the negation but a constituent element of Venetian politics. Indeed, the other and final point is that Venice’s constitutional arrangements were the subject of vibrant and sustained discussions, including powerful transnational echoes. In fact, the ideals of Venice were themselves to some extent elaborated by foreign visitors like, a generation before Contarini, the French ambassador Philippe de Commynes (1445-1511). Contarini’s text was first printed in Paris after the author’s death; in Lewis Lewkenor’s 1599 translation, it became a classic in English political literature. Between the sixteenth and the seventeenth century many authors in both the Netherlands and Poland also looked to Venice as a model, largely on the basis of notions brought back home by well-connected travellers who (for example) were allowed to glimpse at the silent voting procedures in the Great Council, which they described as a spectacle of majesty. One such traveller was James Harrington. In Oceana (1656) he observed that Venice owed her ‘steadiness’ to its capacity to silence disagreement, something which the English Commonwealth failed to do. So here is a last oxymoron: a silent debate. Whether we would call it parliamentary politics, is another question, and there certainly were many critics at the time already, but there is no doubt that Venetian councils had powerful significance for observers throughout Europe.

James Harrington, The Common-Wealth of Oceana, London, 1656. Private collection.

Filippo de Vivo, Professor of Early Modern History, University of Oxford.